There Goes The Neighborhood

To grow up on the East End of Long Island is to grow up with money in the ether. Whether you have it or not, it’s as much a part of the place as the damp, heavy air and the fabled light. In East Hampton, you can see the watermarks of the different eras of wealth that have washed over the town: the stately colonial-era houses along Main Street, the shingle-style mansions of the summer colony, the modernist trophies of the Wall Street elite, and the gargantuan lot-gobbling estates of today’s global titans.

Like many who hail from the East End, Barbara Fiore’s life and livelihood have been entwined with those of the very wealthy for most of her 73 years. She was born on the North Fork and raised on Shelter Island, largely by her grandparents, who worked at Sylvester Manor and the Hench Estate in the 1940s and ’50s.

Fiore remembers the smell of cut grass and gasoline at the manor, the orchards and woods, making a house under a tree, playing in broken-down boats, and skating on ponds with her sister until her grandfather whistled them home; it was so quiet then, she says, the sound of a whistle would carry a mile.

Occasionally her grandmother would dress them up in pinafores and they’d go to visit the main house. “Once in a while — not very often — they’d make ice cream sodas for us in the butler’s pantry,” she said. “We went to school with the owners’ grandchildren.”

As an adult, she ran a custom upholstery business, sewing drapes, pillows, and lampshades for palatial summer cottages like Kilkare in Wainscott; she upholstered everything from high-end sofas

to walls, ceilings, and the seats of pleasure boats.

“I grew up around money, so it was nothing new,” said Fiore. “I learned that people are just as happy with money as without it. But then it started to get difficult — not to make a living, but just to find a place to live.”

She was never short on work. In fact, when she had a store in Sag Harbor she had so much of it she would sometimes shut down for weeks at a time just to catch up. She even owned a house once, a long time ago, but lost it in her second divorce and was never able to buy another. For a long time, it didn’t matter all that much. She’d find places through word of mouth, and even through the real estate boom of the 1980s, she never had any trouble.

She lived in Sag Harbor, Amagansett, Riverhead, East Hampton, Bay Point, North Sea, and, for more than a decade, in a lovely old house in North Haven that she liked so much she made the mistake of telling the landlord that she might like to buy it. He had it appraised, found out it was worth more than a million dollars — far more than she could afford — and sold it to someone else.

For the last few years, Fiore and two other women have rented a three-bedroom house in Hamptons Bays for $2600 a month. It was a great deal and they knew it, but it was also a financial stretch for all of them. She couldn’t work like she used to and her retirement wasn’t enough for her to stay if she didn’t.

So, at the end of June, she moved to North Carolina, where one of her daughters lives. It is the first time in her life she hasn’t lived by the ocean, and she’ll miss its moods and calming presence.

“I’ve thought about it for a long time and knew that this was something I’d have to do, but it’s still hard,” said Fiore last spring, before she left town.

“I wish I could stay but I can’t. This is what I have to do if I want to stop working.”

“It’s my choice,” she said. She had started to cry and paused for a moment to brush away the tears. “But it’s a forced choice.”

• • •

There has always been money on the East End, but so, too, have there always been nooks and corners and crevices not touched or claimed by it. For every mansion-lined Hither or Further lane, there were middle-class Capes on streets like Maidstone Avenue, old Bonacker farmsteads in Springs, and modest little houses along the Bridgehampton-Sag Harbor Turnpike built by African American families who came to work the potato fields and stayed on. There was Montauk and the North Fork, places where fishermen and farmers had lived for centuries.

But over the years, those nooks and crannies have all but vanished. Increasingly, so have the people that used to live in them.

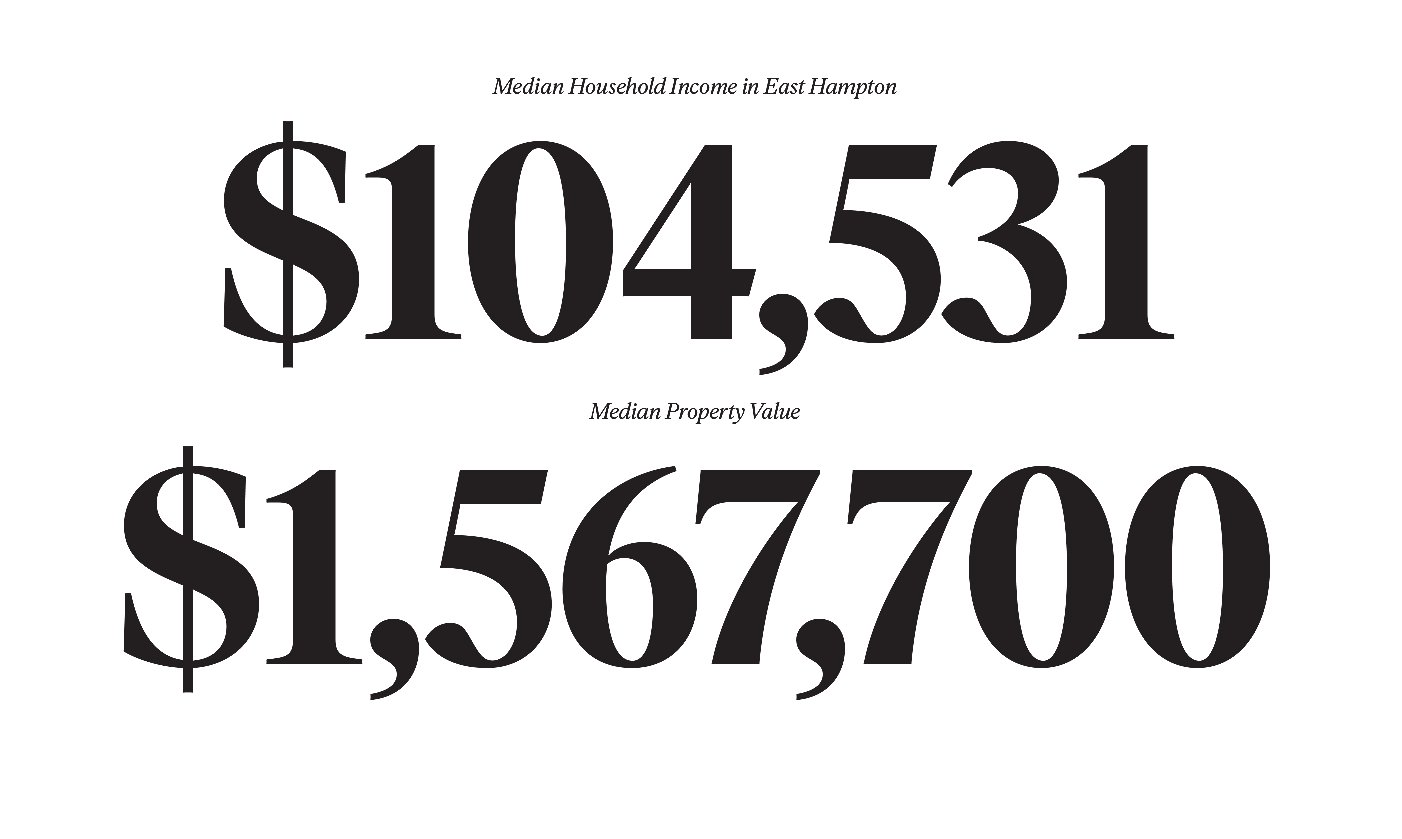

The average home sales price in the Hamptons is $1.8 million. On the North Fork, heralded in the New York press as the low-key alternative where bargains can still be found, it’s $831,000, according to real estate agency Douglas Elliman. Even with a median household income of $92,516 in East Hampton town, about $33,500 more than the national figure, few can afford to buy property anywhere out here. Year-round rental housing is costly and hard to come by, ranging from 12 to a little over 20 percent of the housing stock by town, according to U.S. census data. The economic calculus is almost inevitable: Why rent out your house for $30,000 a year when you can get $10,000 a month in the summer season?

Where there was once a balance between the wealthy and the locals, people will tell you, the balance is gone. Along the way something fundamental changed. Maybe it was the construction of the Long Island Expressway or the Reagan tax cuts or the Wall Street boom or the flush baby boomers who started buying up second homes as their careers took off in the 1980s and 1990s. It might have been 9/11 or the ability to work remotely or rising housing costs or the growing income gap. Maybe social media and Airbnb were the nails in the coffin. Or maybe, as a lot of people suggested, it was as simple as greed.

“It’s a tale of two economies,” said Dave Kapell, the former mayor of Greenport, and now a consultant with the Rauch Foundation, a progressive family philanthropy based on Long Island. “You have the Wall Street economy, which controls prices, and the Main Street economy, which dictates what people can pay — and they’re at war with each other.”

• • •

“I think what happened is, we’ve killed the golden goose,” said Denis Carr. He and his wife Lori Miller-Carr were sitting in the living room of their house, located in a small neighborhood off Springs Fireplace Road in Springs. When I came in, Miller-Carr apologized for the construction mess; they were in the midst of renovations they were undertaking, in part, to will themselves into selling the place so they could afford to retire.

“Everybody loves it out here — the beaches, the weather, the celebrity factor,” Carr continued. “When I came out here for a job in the 1980s, I couldn’t believe it was real. It’s like paradise. It really is.”

But there’s only so much of paradise to go around. As suburban development pressed eastward across Long Island in the decades after World War II, there was legitimate concern in many East End towns that they, too, might fall victim to the sprawl and overdevelopment that had overtaken central Long Island, eroding the charm and rural character of the area. Many towns passed laws that mandated larger acreages per dwelling unit; as a consequence, multi-family development essentially stopped. At the same time, low-density zoning meant that farms, fields, and forests turned into subdivisions and single-family homes, threatening environmentally sensitive lands. This, in turn, spurred open-space conservation programs in a number of towns, including a two percent real estate transfer tax in the towns of East Hampton, Riverhead, Shelter Island, Southampton, and Southold that has, to date, preserved more than 10,000 acres.

“I always said the better job you do of preserving the community, the more it becomes desirable and drives up prices,” said Tom Ruhle, the director of housing in East Hampton town, which is now about 40 percent open space, wetlands, or otherwise protected land.

That certainly proved to be the case on the East End. Because while those open-space conservation programs were well intentioned, widely popular, and, from an environmental standpoint, absolutely critical, they had the unintended consequence of making developable land scarcer and therefore more valuable. And when you factor in the growing income gap — the share of national income that has flowed to the top one percent since 1980 has more than doubled, according to the Journal of Quarterly Economics — the local market had all the makings of a perfect storm, with the richest Americans enjoying a growing share of the buying power and, increasingly, determining the prices. Suffolk County also has about 37,000 second homes, one of the densest concentrations in the country, according to the Suffolk Planning Commission.

All of which means that the Carr-Millers’ generation of middle-class locals is likely to be among the last to buy or build homes here.

Carr used to be the photographer for the Sag Harbor Express; Miller-Carr was the secretary for the Town Trustees. They also owned Reed’s Photo Shop in town, from 2006 until it closed in 2013.

They married in 2003 and that same year used money from the sale of a house Miller-Carr had bought for $115,000 in 1998 through a low-income mortgage program to buy their current home for $415,000 — about the going-rate these days for a vacant half-acre of land.

Both are semi-retired; Miller-Carr stayed on part-time with the trustees and Carr works for East Hampton’s ordinance enforcement office three days a week in addition to doing some freelance photography. Hence, the renovation. With prices rising in less expensive East End locales like Riverhead and Hamptons Bays, in part due to the influx of people like them coming from points East, they feel that they’ll have to sell soon if they want to stay in the area.

“I don’t want to move. I hate to do it. I’m 13th generation,” Miller-Carr said. “But we have to take advantage of the housing market.”

Miller-Carr’s father, Milton Miller, was a bayman and a coast guardsman who grew up in a cottage by Atlantic Beach and used to hang out with whalers — his mother would chase him down with a broom for neglecting his chores. At one point, Miller said, her family owned a big percentage of Old Stone Highway to Louse Point, “but they sold it off because they didn’t know the value. The only piece of Miller land left is what we’re sitting on.”

Miller-Carr also wants to stay close to family in the area, including her daughter, who lives with her in-laws along with her husband and three daughters. Her son, however, is already gone, having moved to North Carolina with his wife and son in December. He’d been working as a mechanic in Amagansett during the day and repairing taxis at night, working 12 to 14 hours a day. “He just turned 35 and he already has carpal tunnel. He was tired, tired of working two jobs. They just wanted a better life where he wasn’t working all the time,” she said. Now he has a better paying job and a four-bedroom colonial on more than an acre of land; one of the other mechanics at his old shop is thinking about moving down as well.

“He had to leave,” Miller-Carr continued. “Well, he didn’t have to.”

“Well, he did,” said Carr. “Once one goes, it starts a trend. We’re constantly hearing about this person left, that person left.”

“If they have the means to go, they go,” said Miller-Carr. “They could stay, but they’d have to work themselves to death.”

• • •

“If we didn’t have this living situation, I don’t know what we’d do,” a 34-year-old farmer told me back in March. He was living with his fiancée and their two-year-old daughter in a one-room cottage behind her parents’ house in East Hampton, traveling each day to Amagansett to work on an organic farm. His fiancée, whom he met on the farm, has been living in the cottage since graduating from college; it was a great space for one, good for two, and fine for two and a baby, but less than ideal with a toddler.

“When I first started coming out here to work on the farm,” he continued, “I knew I wouldn’t be able to afford a place to stay, so I lived out of my car a lot of the time. It was a fantastic way to save money and I did it for about six years. Even now we’re minimalists, but we’d like two rooms.”

They’d been looking for a little house or cottage for a few months without much luck — the most they could afford to spend was $1100 or $1200 a month, about double what they were paying her parents, thanks to a sweetheart deal, but about half the market rate. By early May, he still hadn’t found anything and they were thinking, quite seriously, about leaving the area. He asked me not to use his name lest his employer learn he might not be around too long.

“We both love it here; it’s beautiful. But there are times when you get jaded, when you just see such opulence and you’re just scraping by,” he said.

“You know the Stephen Talkhouse in Amagansett?,” he continued. “A few times a year they’ll hold a fundraiser to help a family pay their medical bills. We’re funding medical bills through benefit parties. And meanwhile, down the road you see someone is putting a huge extension on their house. That’s an indication that the system is messed up.”

As common as it is out here for adult children to stay at home until their 30s or even 40s, not everyone wants to live that way. And with the younger generations increasingly unable to make the numbers work, the population on the East End is, not surprisingly, aging: In East Hampton town, the median age has gone from 40.1 years in 1990 to 51 years in 2017, according to census figures.

Towns complain that they can’t keep teachers or firefighters, nurses, or even doctors. Route 27 is dotted with signs from the volunteer fire departments looking for recruits. Pam Balserus, the Bridgehampton Fire District secretary, said it isn’t a problem recruiting firefighters in their early 20s, “but as soon as they get a little older and we’ve trained them, they leave. How can you tell a 28-year-old who wants to get married and start a family that it’s going to cost $800,000 to buy a house?” she asked.

Some do commute in from the less expensive towns to the west, but with the traffic on Route 27, it’s a draining prospect, one that tends to leave both the people and the East End towns where they work feeling depleted.

“There’s a sense of loss when people like your teachers and nurses don’t live there anymore, when the nurse can’t go back in if there’s an emergency or the teacher can’t stay to see the school play at night,” said Jay Schneiderman, the Southampton Town Supervisor. “The community kind of loses its soul in a way.”

Bonnie Cannon, the executive director of the Bridgehampton Child Care & Recreational Center, described it as “kind of a ghost-town feeling when all the local people are living up-island.”

And with multiple generations living in the same house or property, a parent or grandparent’s decision to relocate often displaces younger generations as well. Bernette Schoenster, in East Hampton, told me that she’d made the decision to move to Ocala, Florida after looking over her family’s finances and realizing that her husband, an electrician, was going to have to work until he was 77 if they stayed.

“And I’ve seen a lot of people work until they’re 77 and when they retire, they die,” she said.

Schoenster’s retirement plans will, however, displace all four of her adult sons. One lives with her, in the house her husband built in the 1990s on Three Mile Harbor Road, when the neighborhood was still, as she put it, “all clammers and scrappers and people without.” The other three men live in her deceased mother’s house on Springs Fireplace Road.

“They don’t pay me rent and they couldn’t afford to,” said Schoenster. “I’ve told them to put in applications for low-income housing because when I sell, they’ll be homeless.”

“I think the financial struggle has pushed a lot of the original heritage families out,” she went on. “My kids are never going to be original Bonackers and have a little house in the woods. All that’s left is millionaires and low-income, striving families.”

Her son, Devon Grisham, 28, a custodian with the East Hampton school district, said that he has no plan for what he’ll do if his mother sells the house. “I really try not to think about it,” he said.

He started his custodial job five years ago at her urging — it offers full benefits and a retirement plan. Before, he’d been working as a mechanic at a motorbike shop, which he liked, but it paid $14 an hour. In the summers, he also picks up landscaping jobs and works as a commercial fisherman in Montauk; if he has to move west for cheaper rent, he’d have to give up the fishing because of the long commute and the early hour the boat pushes off from the dock.

“Catching fish, the fight of it, never knowing what’s going to bite, especially off Montauk, I love it,” Grisham said. “The town is trying to build affordable homes, but to me it’s like segregation. You have to live by these laws, you can’t do this or you can’t do that in your driveway. I like to work on my boats and listen to music. I don’t know that I’d be able to do that there.”

Younger locals with their own houses are so rare that I heard of only two in the course of reporting this story. I met one of them, Mark Barylski, at the Townline BBQ in Sagaponack. Barylski, who is 27 and works for his father’s surveying company, told me that going out for a beer after work wasn’t a normal thing for him; if he wanted a beer, he’d buy some on the way home and drink it there to save money. “My fiancée and I love going to the movies, but we’re already paying $10 a month for Netflix, so we watch that and cook,” he said.

But while thrift certainly helped him on the path to home ownership, the route he took there was so singular and superbly timed — a multi-tiered plan that involved buying an old trailer for $80,000, rehabbing it and re-selling it at the peak of the trailer market for $205,000, convincing his uncle to sell him a half-acre of land in Springs for $250,000 (about $100,000 less than it would’ve fetched on the market), then buying a modular home from Pennsylvania to sit on the land (building one locally would have been more expensive) — that it seemed unlikely many of his peers would be able to repeat such a feat.

Almost all of his other friends live at home, aside from a few who got good deals on foreclosures and a few who inherited their grandparents’ houses.

“Most of the places we survey, it’s great we have the work, but about twice a week, we see a little house, a two-to-four bedroom house, a normal house a little family could live in, and they’re tearing it down, or putting up big additions, patios, pools,” he said. “We see a lot of beautiful houses, but sometimes you’re like, ‘It’s piggish.’ We have a saying about the huge houses people build on those kinds of lots: 10 pounds of shit in a five-pound bucket.”

• • •

The receding prospect of middle-class home ownership wouldn’t be such a problem if there were viable alternatives, but the local rental market has a tendency to be both capricious and cruel, characteristics that seem to have only been heightened by the arrival of Airbnb.

“Year-round rental housing has been in crisis for quite some time, but just a few years ago for $2500 a month you could get three beds and a bath in an older rental or Cape in Sag Harbor,” said Simon Harrison, a broker and founder of Simon Harrison Real Estate. “Twenty-five hundred doesn’t get you much anymore. You might get an occasional two-bedroom apartment for that.”

Now that three-bedroom cape rents for closer to $3500 a month; a family would need to make a household income of more than $125,000 a year to qualify. In Montauk, the average percentage of income spent on rent is 37.5; in Southold it’s 44.8 percent. Anything over 30 percent is considered rent-burdened.

But, Harrison added, the increased rental price wasn’t necessarily greed on the part of the landlord: higher sales prices mean bigger mortgages and carrying costs, which are passed on to renters. And because so many locals now rent out rooms in their houses or clear out entirely during the summer, using the seasonal windfall to manage what would otherwise be unfeasible mortgages, it’s hard to disentangle the various markets.

Besides being expensive, rental housing in a seasonal economy is often precarious; I talked to many people who’d had wonderful, reasonably priced places until the owner decided to sell or turn it into a seasonal rental.

And desperation can make renters vulnerable to scams and deceptions. Several people described being rented homes they later discovered were going through foreclosure. Eimmy Torres-Vasquez moved into her cottage in Montauk on the day she got married, July 28, 2018. It was $1500 a month and about as much as they could afford to pay, but she and her husband felt so lucky to find it. They had a one-year-old son and they’d never lived together as a family before — neither of their relatives had space for the other to move in.

“Then we found out it was in foreclosure, we weren’t even supposed to be living here, and there were heat problems,” she said. “The boiler wasn’t working last winter, so we set up space heaters and ended up with a $600 electric bill.”

Another woman, Sue Alioto, who’d grown up in Sag Harbor, told me she’d been renting an illegal basement apartment in an elderly couple’s Jamesport home for eight years. After they died, she hoped their son would allow her to stay at $850 a month. But he never contacted her; over time it became clear that he’d stopped paying the mortgage and the house went into foreclosure. “One day, the electricity shut off, but I stayed an extra two weeks. I didn’t want to leave. It was my home, I was walking around with a flashlight,” Alioto said. “I couldn’t bring myself to leave.”

Her daughter finally said, “Ma, you can’t live like this. No electricity, no heat.”

She’s been living with her daughter and son-in-law in Riverhead ever since and is on the waiting list for an over-55 community there, but worries she won’t have the money when her number comes up. “It’s $1099 for a one-bedroom plus electric. I have to save, but every time I save something happens,” she said. “In December it cost $2000 to fix the car engine and then on Monday I needed a new exhaust. It’s a situation I have no control over. All I can do is work and wait and save my money.”

• • •

Though towns have been building affordable housing since the early 1980s or ’90s, it’s been at a far slower pace than the rate at which working class and middle-income housing has been lost.

“I hate telling people the time on our waiting list,” said Ella Engel-Snow, who works at East Hampton’s Whalebone Village apartments, the first family affordable housing on the East End, which opened in 1989 (the year after she was born). “We tell them it’s about eight to 10 years, but honestly I think it might be longer by now.”

“Recently my co-worker and I have started looking online at places like Bonac Rentals on Facebook to try to help find places, but that’s really not part of our job,” Engel-Snow said. “And there’s really nothing.”

There is, at this point, broad consensus on the East End that new development is the only way out of the affordability crisis. And a number of units are currently planned or under construction, among them a 38-unit development on Montauk Highway in Amagansett, 50 units on North Road in Greenport, 38 units by the Speonk train station, and 116 units on East Main Street in Riverhead. That’s not remotely sufficient to solve the problem, but every bit helps.

There are other encouraging signs, as well: A bill proposing to add a 0.5 percent transfer tax on property sales to fund affordable housing construction passed the state legislature in June and is now awaiting the governor’s signature. In Southampton, a new accessory apartment law targeted at the least affordable parts of town passed this spring, reducing the acreage required to build an accessory apartment (to half an acre, down from three-quarters) if the apartment meets affordability requirements. And in an attempt to address some of the symptoms of the problem, if not the problem itself, a new train and shuttle commuter service launched in March to relieve congested rush hour traffic on Route 27.

Still, even with the majority of residents now acknowledging the need for affordable housing, Schneiderman said people often fight every single particular of a project and insist on such low density that it can’t be built without substantial subsidies. With Speonk Commons, for example, which is currently under construction, the town found a developer willing to build 51 units, but “the community went wild, they were really upset about the density,” said Schneiderman, who eventually convinced the project’s opponents to accept a 38-unit development. But the project then required a $1.5 million subsidy because it had fewer apartments than what the developer needed to break even.

There is a sense that with things so bad, something will change, if only because it has to. Michael Daly, an Elliman broker in Sag Harbor who’s also on the Southampton Zoning Board of Appeals, told me that he’s developing an East End YIMBY, as in “yes in my back yard,” to educate people about affordable housing and make sure they come to meetings to stand up to what he refers to as the “CAVE people” — citizens against virtually everything.

“The problem is, most people support affordable housing, they see it on the town agendas and they say, ‘Oh good. It’s about time they put it on there,’” he said. “And then they sit home watching ‘House of Cards’ in their footsie pajamas during the hearings while all the NIMBYs run out.”

Kapell, the former mayor of Greenport, said that towns on the East End should be doing everything in their power to change their zoning to allow for more density, more rental units, and the creation of municipal sewer districts and other infrastructure to support that density.

“In cases where affordable housing is being developed, there are enormous public subsidies to bring down the cost. What you have is the taxpayer subsidizing bad zoning,” Kapell said. “To think it’s going to solve things is whistling Dixie.”

It will also require moving from the home ownership model to the rental model, he added, a point echoed by a number of other affordable housing advocates. Only a handful of Long Island communities have more than 30 percent of homes occupied by renters, according to a report from the Regional Plan Association, and those rentals are concentrated in the same areas they were 40 years ago.

Still, re-aligning economic incentives isn’t easy. In his 2005 book “Living and Working in Paradise,” affordable housing expert William Hettinger wrote about the efforts of Aspen, CO, to devise a strategy to keep the middle and upper-middle class, as well as low-wage workers, from being priced out of the market. The first affordable housing development opened in 1978 and by the mid-’90s the town had imposed an extra sales tax and instituted a real estate transfer tax to fund affordable housing. But today, Aspen, for all its good intentions, still only houses approximately 40 percent of its workers. And in towns like Vail, Breckenridge, and Telluride, a much larger share of the workforce lives out of vans or makes hours-long commutes over snowy mountain passes.

“What’s happened in the last 15 years is the problem has gotten worse and it’s spread from some resort communities to all resort communities,” Hettinger told me. “Cities that didn’t think they had problems, now have problems.”

And that isn’t just true of desirable, land-constrained cities like New York and San Francisco and resort towns like those on the East End. It is a crisis that’s now affecting large swaths of the country, including unlikely spots like Plano, TX. Wages simply haven’t risen nearly fast enough to keep pace.

“The housing market has reached an affordability ceiling,” said Cheryl Young, a senior economist at the housing website Trulia. “After the recession, we basically stopped building and a lot of people left the construction industry. What characterizes the housing market right now is undersupply.”

But while home ownership may be beyond the grasp of a growing number of Americans, it remains one of our most compelling aspirations. It’s the most common way for the middle class to build equity — all the more important in an era of diminished work benefits and social programs — and it represents not only the freedom to paint the walls and work on your boat in the driveway, but to stay or leave on your own terms. One of the questions on Trulia’s housing survey is whether owning a home is an important thing to do. Almost everyone, said Young, answers “Yes.”

• • •

Freedom was something that came up a lot in my conversations with East Enders: the way you used to be able to ride a horse on the bridle paths from East Hampton to Montauk, the way locals teenagers used to party at the beaches before it got banned because enormous flash mobs of tourists were pulling up in Ubers, the way you used to be able to grab a boogie board and cool off on a hot day without someone taking a photograph and trying to sell it to you as a souvenir of your “surfing experience.”

Even in a best-case scenario, in which the towns managed to meet 100 percent of the affordable housing need, it seems unlikely that much of what has been lost could be restored. It used to be that Labor Day was when locals would reclaim their towns, when all the slights and mistreatments, feeling put upon and looked down on, would end, at least until the next summer. Now tourists come deep into the shoulder seasons and the strain is evident. One man told me that he liked Montauk best in January, the only month when it reminded him of the way it was when he was growing up.

Many people who’ve moved away described it as an almost magical experience, like being freed from a spell they hadn’t realized they were under. Dina Ricker, whose dad, Joe Ricker, was the voice of WLNG in Sag Harbor, told me about all the years she and her husband were always just scraping by, working multiple jobs, moving to dumpier and more expensive rentals every few years, having to rely on the food pantry after they had their daughters, and working opposite shifts to avoid using day care. One day, she walked into a Sag Harbor bookstore and saw an ad in the Sedona Journal for a retreat in Mount Shasta, CA. “I don’t know what it was, but something drew me in.” Tight as money was, she went to the retreat and the next year, 1997, she and her husband decided to move.

“We never looked back,” she said. “It was the best thing we ever did.”

Kathryn Bermudez, 29, was born and raised on the East End, the daughter of Colombian immigrants who were among the first wave to work in the area, but last year she and her husband moved with their seven-year-old daughter and two-year-old son to a town in central Long Island. They’d been paying $2000 a month for a studio and after nine months of searching couldn’t find anything bigger for less than $3000 a month. They were on the verge of accepting her father’s offer to come and live with him in Colombia for the summer when they got a call from the owner of a small ranch house in a subdivision Bermudez had reached out to three months before.

The first six months were hard, she admitted. She missed being able to run over to her mother’s apartment in Amagansett for a home-cooked meal or childcare. “I knew everyone there and everyone knew me,” she said. “But moving from the Hamptons has opened up our life in a variety of ways,” she said. Her husband found a job at a car dealership, making much more money than he had doing pool maintenance. Their house, while still $2300 a month, has three bedrooms, a playroom, and a yard. She literally saves hundreds of dollars a month on groceries.

“Being a native of Amagansett, we’d love to own there. It’s beautiful. But I can’t buy a $5 million house and I can’t afford to rent a $3500-a-month three bedroom. I’m very happy that I’m still close to our hometown, but I am also living in a place with a new beginning.”

Ron White, a real estate agent with Saunders who grew up in Bridgehampton, the great grand-son of a migrant worker, said that the story he most often hears people tell about leaving isn’t one of despair, but of opportunity. “Many of us locals were in the first or second generation who had the ability to go to college,” he said. “After you have the education, you’re making money, and you see how far your money goes somewhere else, it makes no sense to come back.”

Of course, many are determined to stay, come what may. Mike Martinsen has been working as a commercial fisherman in the area since 1994. When he and a partner launched Montauk Shellfish Company, an oyster farm in Montauk Harbor and Block Island Sound, in 2009, it seemed a perfect example what a conscientious local business should be: tied to old traditions and industries while embracing new techniques and environmental realities, poised to take advantage of the tourism economy without being dependent on it.

It didn’t work out that way, though. The company had investors, good press, multiple farm sites, and was training and hiring people en route to raising 10 million oysters a year. But in the end, they just couldn’t find enough workers for what they could afford to pay — about $20 an hour. Martinsen doesn’t blame them: even $25 an hour wouldn’t be enough to live in Montauk.

So two years ago, Martinsen bought out his partners and has been trying to run a much-reduced operation with his son in the hope of turning a profit this year. “I’ve been working solo all winter, trying to figure out how to make it work,” he said. He has larger dreams for a future in aquaculture and Montauk, 120 miles out into the Atlantic, is the perfect location.

“Right now I’m farming the bay, but my dream is to be farming the ocean,” Martinsen said. “Even if I can’t make this work, I’ll go back to commercial fishing. I’m very strongly committed to the community, I love the town, I’m in the fire department, and I have a lot of friends here.”

But that commitment isn’t an easy one to keep.

A few years ago, he had to move into a tent with his girlfriend and their three kids after the landlord of the house they were renting called them on Mother’s Day to tell them they’d need to clear out by June for a summer rental. After trying and failing to find another rental, a friend offered to let them pitch a tent behind her house.

It seemed like one of life’s low points, but in fact, “one of the fondest memories I have is living in the tent with my kids,” said Martinsen, who now lives in another Montauk rental, which he said he only has by the grace of god and the kindness of the community. “We’d have a campfire at night, we’d read, we’d recognize the different sounds of the birds as they flew by, the swans and the herons. When we finally spent a night indoors during a storm in October, it was like putting your hands over your ears.”

“A lot of people out here have been through something similar,” he added. “Every home now is a private rental for the summer. I’ve thought about buying a house, but the only way I can is if I rent it out for the summer — and go live on a boat.”

Kim Velsey is a frequent contributor to The New York Times and has also written for Crain’s, Surface magazine and Architectural Digest. She was formerly a senior editor at the New York Observer and a staff writer at the Hartford Courant.

Photography by Eric Striffler