Vistas Gone: We Used to See Hamptons Pastures and Oceans Forever

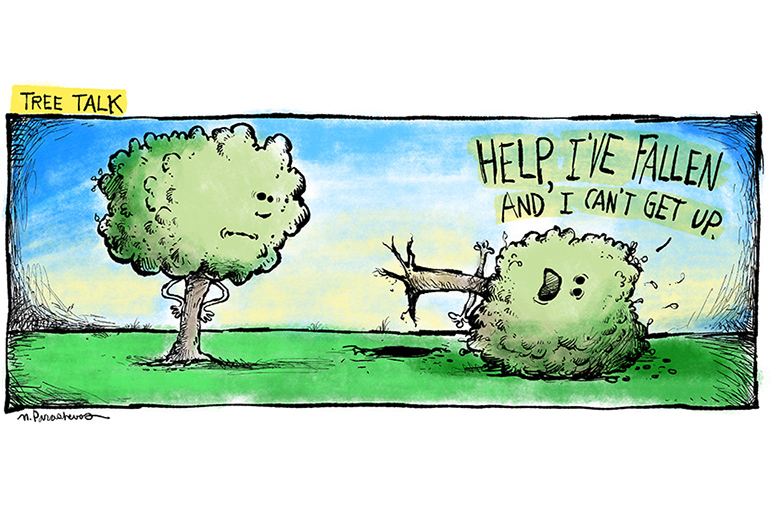

A local judge issued a temporary restraining order two weeks ago after a clear cutting of what has been estimated to be between 75 and 100 trees from the 5.9 acres owned by 341 Town Lane LLC in Amagansett.

The announcement came from the Peconic Land Trust, which oversees permanent easements voluntarily put on certain properties in our community. Property owners agree to them—this one promising to keep this property in an “open, undeveloped and scenic state”—sometimes in exchange for the granting of hoped-for decisions in other land management matters, and sometimes they agree to them simply because they are environmentally sensitive. After all, the birds and the bees have to live somewhere.

This particular permanent easement was put on this property by its owners back in 1995. This LLC, of which billionaire Randy Lerner is principal, is the second new owner of the property since then. Easements and other encumbrances on properties are typically made known to buyers by the due diligence done in title searches.

According to a Peconic Land Trust press release, they sent a cease and desist order to the new property owners. That release also calls the violation egregious and extreme. The owners have lawyers and they will explain the case for taking down all these trees, as this legal case moves through the courts. Among the mature trees removed, according to the Peconic Land Trust, were American Beech, Sassafras, White Oak and American Holly. In the end, if found to be in violation, the owners will be required to restore the property to the way it was.

These kinds of easements are not the only ways that our local governments and institutions protect our foliage and environment. There are laws that prevent the disturbing of wetlands, and there are other laws that require permits before the cutting down of trees.

When my dad first brought his wife, me and my sister out to the East End in 1955, there were vast areas of this community that were treeless. You could see the ocean in every direction. There were hills and dales. And the prevailing weather was windy, damp and salty. You knew you were on a peninsula sticking out into the ocean.

In the last half-century, things in this regard have changed dramatically. We are now surrounded almost everywhere by beautiful greenery, flowers and trees. The prevailing weather now has a much more inland feel. And the temperature gap—the difference between the city temperature and the East End temperature—has narrowed.

If no one told you so, you might not even think there was an ocean here.

There is a photograph of me that shows all this. It was taken of me and my dog Pi on South Fairview Avenue in Montauk. I am a teenager standing on the shoulder of the road. The front lawn of our house is between me and the camera. The house across the street sits on lawn unencumbered by bushes or trees, the Montauk Downs Golf Course just beyond. Today, you couldn’t even take this picture. The front lawn of our old homestead is filled with flowers, trees, trellises and foliage. Across the street, the house there still stands, but it too is shrouded in foliage. And there is no sign of any golf course.

This year is the 50th anniversary of a major event in the Hamptons, when some New York hippies filled with hope took off from a huge open pasture in Springs in an inflatable balloon called The Free Life, attempting to cross the Atlantic to Europe. A crowd was there, me among them. They flew low out over the pasture for almost a half a mile, past the only tree in this field, before they reached Gardiners Bay and Gardiners Island beyond, and out there they lifted off and sailed away—to never be heard from again.

Rescue efforts, conducted over the Atlantic Ocean during the rest of the week found no trace of the balloon. Sorrow and tears in this community followed. It was a sad time.

Random House published my book In the Hamptons in 2009, and it had a chapter about The Free Life in it. I did a reading once for a small crowd, standing by the road adjacent to this pasture to share this sadness with new friends. But it was a pasture no more. I read about the scene. But now it was woods. You couldn’t see more than 50 feet.

Anyone who has been here for the last half-century knows of this startling change in the landscape. About 10 years ago, the East Hampton Town Board, composed almost entirely of local people, decided to do something about it. Many roads end at the beach. It was proposed to clear the foliage away at these road ends, and at other places where views once were but are now blocked, so the population could once again enjoy what we once did. It was received enthusiastically when proposed, but the public was horrified and nearly unanimously against it—so the plan was dropped.

What had caused this dramatic change? At first I thought it might have been the Hurricane of 1938. This was a disaster of catastrophic proportions for the Hamptons and perhaps all the old trees were simply swept away. That would explain what this place looked like when our family got here. It wasn’t that long after the hurricane.

But now I think this dramatic change was caused by landscaping. During the last half-century, so many mansions in these parts have undergone dramatic landscaping projects. Trees from Japan have been brought in. There are flowers and bushes we had never seen before. For a while, bamboo was in fashion. To my knowledge, it never occurred to anyone that this delicious and fabulous landscaping meant a massive unleashing of pollen. A rich man makes his property look like an English garden. Suddenly exotic plants are growing in the neighbor’s yard. And then the yard next to that. Pretty soon it’s the Garden of Eden everywhere.

This is not to say that this is not a good thing. I am not grousing about the good old days now gone that were better than now. It’s all just different.

It’s also true that having massive amounts of foliage helps the global warming situation. Plants take in carbon dioxide and release oxygen.

But I think if the owners of this Amagansett property were to look at old photographs of the 5.9 acres, they might find that long ago there were no trees on it all. In fact, I bet that is very likely.

And if it is, could they make a case out of the fact that’s the way it was before the zoning, and so the treeless state could be grandfathered in?