Kennedys Used Their Power To Kill Wind Farm

If developers of the South Fork Wind Farm ever doubted the resolve of powerful opponents to stop the project, they need only take a look at what recently happened in Massachusetts.

Deepwater Wind, which has since sold to Ørsted, wants to bring a cable carrying power from 15 offshore wind generators to a landing spot on Beach Lane in Wainscott, and then run the cable underground to a PSEG facility four miles away. Since the inception of that project, the company has heard ominous warnings that ultra-rich residents would use their connections and money to put the kibosh on it.

It wouldn’t be the first time. A plan to build electricity-generating windmills within a rock-skip of another one of America’s wealthiest and most scenic areas is officially dead in the water after years of red tape and resistance.

The Cape Wind project, which envisioned 130 turbines built off the Massachusetts coast, would have been the first U.S. offshore wind farm. But the developer and its investors failed to consider that on a clear day the turbines would be visible on the coast — including estates owned by the Kennedy family, one of the most powerful Democratic dynasties in the country, and William Koch, whose brothers are two GOP stalwarts.

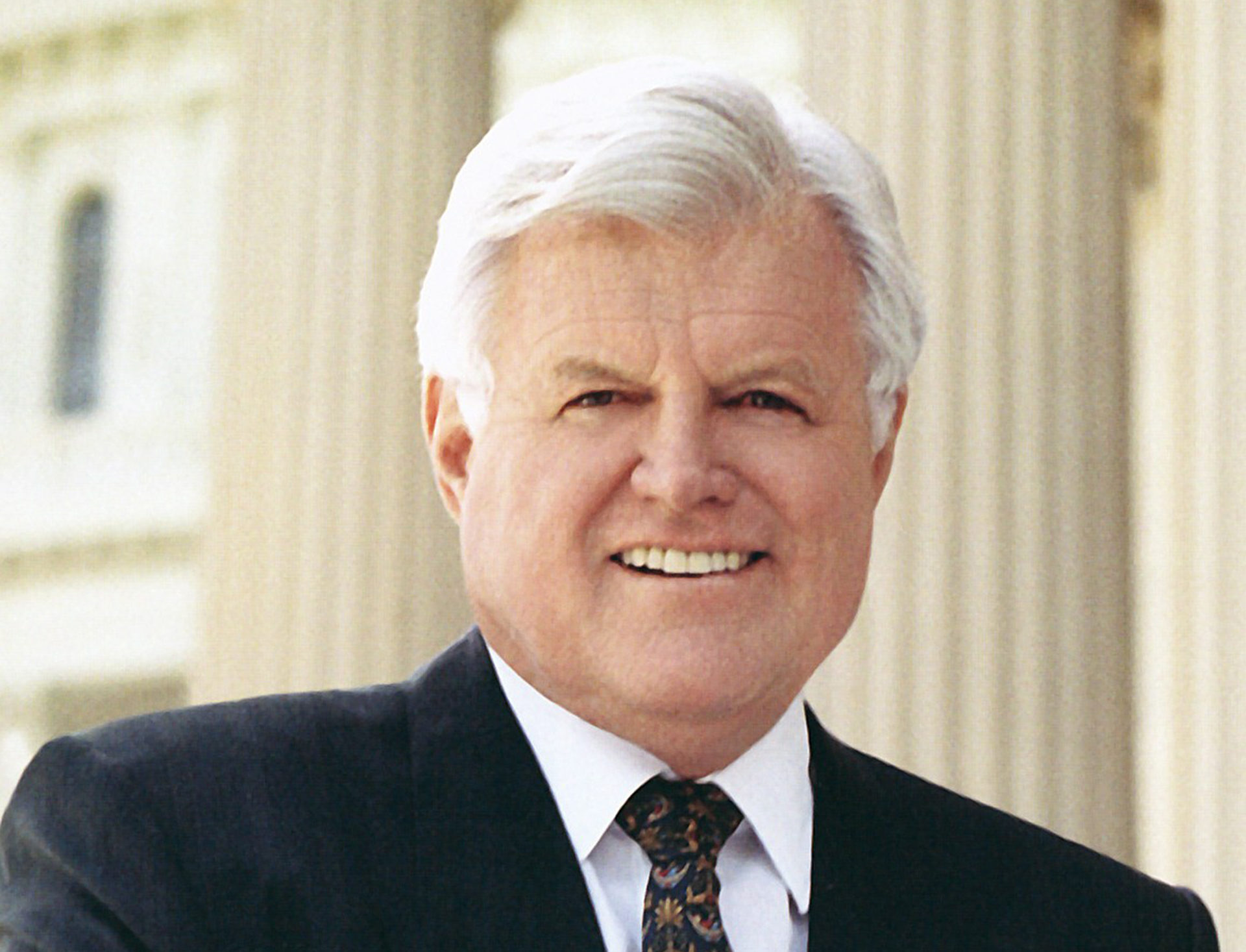

Though at opposite sides of the political spectrum, Senator Ted Kennedy and Koch found common ground in their desire to stop the wind farm at all costs. Like Deepwater, Cape Wind jumped through myriad state and federal hoops and spent freely for the necessary tests.

Senator Kennedy opposed the project from the outset. And if history has taught us anything, it’s that the Kennedys know how to use their clout.

According to a report by Fox News in 2017, Koch, the industrialists whose brothers Charles and David are well known for their bankrolling Republican politicians, found common ground with Kennedy — he didn’t want the wind farm either. He purchased a 26-acre waterfront estate near the Kennedy compound in 2013 for $19.5 million and quickly turned his attention to combating what he called the “visual pollution” from the Cape Wind project. “I am confident that the project’s lack of merit will result in its demise,” Koch told the New York Times.

“Senator Kennedy has real environmental and economic concerns,” a spokeswoman for the senator said.

Robert F. Kennedy Jr. was enlisted to oppose the project, as were many fishing groups that already had concerns about the effect of wind production on fisheries.

The verbal assault went on for years, and Cape Wind investors finally pulled the plug. “We are proud of the catalyzing and pioneering effort we devoted to bringing offshore wind to the United States,” Cape Wind president James Gordon said in December 2017.

Though the South Fork Wind Farm is in the process of review — though critics contend, moving at a snail’s pace — Ørsted insists it is on schedule to go online in 2022.

Vineyard Wind, another planned wind farm in the same waters just 14 miles south of Martha’s Vineyard and Nantucket, also stalled. Construction was to begin in 2019. It is another of several offshore wind farms planned on the Atlantic Coast, as Ørsted has two others in the hopper.

Once again, those with fishing interests cast a wary eye, and the U.S. Bureau of Ocean Energy Management decided to launch a “cumulative impacts analysis” that could drag on for some time. That would mean tax credits needed to fund the construction could expire next year.

The South Fork Wind farm is also relying on tax credits — and the clock is ticking.

Earlier this month, The New York Times suggested Wainscott residents, like cosmetics billionaire Ronald Lauder and American television producer Marci Klein, had lined up against the Wainscott landing site. Neither has commented publicly.

Ørsted has taken notice though, advancing an alternate landing site for the cable in Montauk. The trouble is, a lot of powerful people who don’t want their bucolic lives to be interrupted live there too.

rmurphy@indyeastend.com