Remembering the Abandoned Northwest Harbor Settlement

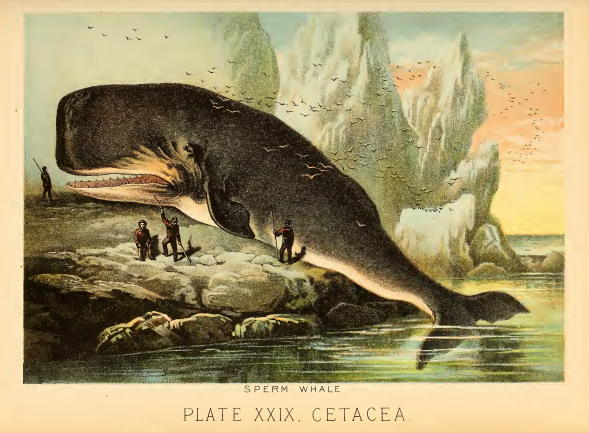

Live by the whale, die by the whale. The abandoned village in East Hampton’s Northwest Harbor grew up around whaling, but was vacated once trading there was no longer profitable. Now there is almost nothing left of this once-thriving community.

Four years after the first settlers arrived in East Hampton, the town records of 1653 mention “A cartway to ye Northwest meddow.” The Northwest contained the port that East Hampton needed for trade.

In 1665, a merchant ship from Boston landed in the Northwest, but it didn’t pay duty on its cargo. Not so fast: within two years East Hampton had appointed a “Collector of Port” and established tax rates for all goods coming through its ports.

Whale oil was the major item that East Hampton traded, and whaling began very early. In 1700 Abraham Schellinger built a wharf at Northwest Harbor to service whaleboats and in 1702, Samuel Mulford built a wharf and warehouse at Northwest Harbor. Besides whale oil, the port shipped out livestock, wood, bone, and furs, while rum, molasses, cocoa, indigo, spices, and mahogany were shipped in from New England and the West Indies.

Oh ho, not so fast, said the New York Colony authorities. Eastern Long Islanders made Boston or Connecticut their trading port rather than New York simply because it’s closer. By 1684 an act was passed levying a duty of 10 per cent on all oil and bone exported from New York to any outside ports except England or to the West Indies.

Long Islanders just ignored it. For example, in 1703, one whaler’s company brought in 120 barrels of oil valued at 240 pounds. Yet London customs records show only about 120 barrels total imported from New York that year. Clearly, Long Islanders just refused to ship their oil through New York and paying the New York taxes. In 1702, the East Hampton Trustees recorded that thirteen whales had been killed from stations at Mecox, Sagaponack, and East Hampton, carted to the Northwest, and were then sent to Boston and on to London. London customs recorded that only 38 gallons of oil had come from New York in 1702.

New York wasn’t finished trying to get some of that sweet whaling cash, though. In 1696, Lord Cornbury became governor of New York, and announced that the whale was a “Royal Fish,” and belonged to the king; so all whalers had to be licensed. Oh, and also whalers had to “contribute good part of the fruit of their labour; no less that a neat 14th part of the Oyle and Bone, when cut up, and to bring the same to New York.” Few Long Islanders complied.

Flush with cash, by the 1700s, the Northwest boasted fifteen farms (mostly for grazing since the soil is poor), a mill (a tide mill, which works on the changing tides), wharves, warehouses, a pest house (a refuge for people with contagious disease), a fish factory, a sawmill and a public school. About 40 families lived there: to the west from Scoy Pond to the harbor, and along a curve of the beach to the northwest of the harbor.

One of the families were the Van Scoys. Isaac and Mercy Van Scoy had fifteen children; Van Scoy farmed and harvested shellfish for a living. During the Revolutionary War, the British fleet happened to be in Gardiner’s Bay and they often raided the nearby Van Scoy farm. Isaac kept a sharpened pitchfork by his bed, and one night he killed one and injured two British soldiers raiding his house. He was arrested, but escaped and lay low in the woods until the end of the war.

But by then, the Northwest settlement was in decline. Long Wharf was built in Sag Harbor in 1770. The Northwest harbor was much shallower than Sag Harbor and unable to accommodate the larger ships then being built. By the 1780s all significant trading by water occurred at Sag Harbor.

The settlement at the Northwest Harbor–with its wharves, warehouse, school, and mills–disappeared entirely by the end of the nineteenth century. Farming its poor soil wasn’t profitable and the whale trade had ceased. Little is left except for a small cemetery where Isaac and Mercy Van Scoy, among others, are buried.