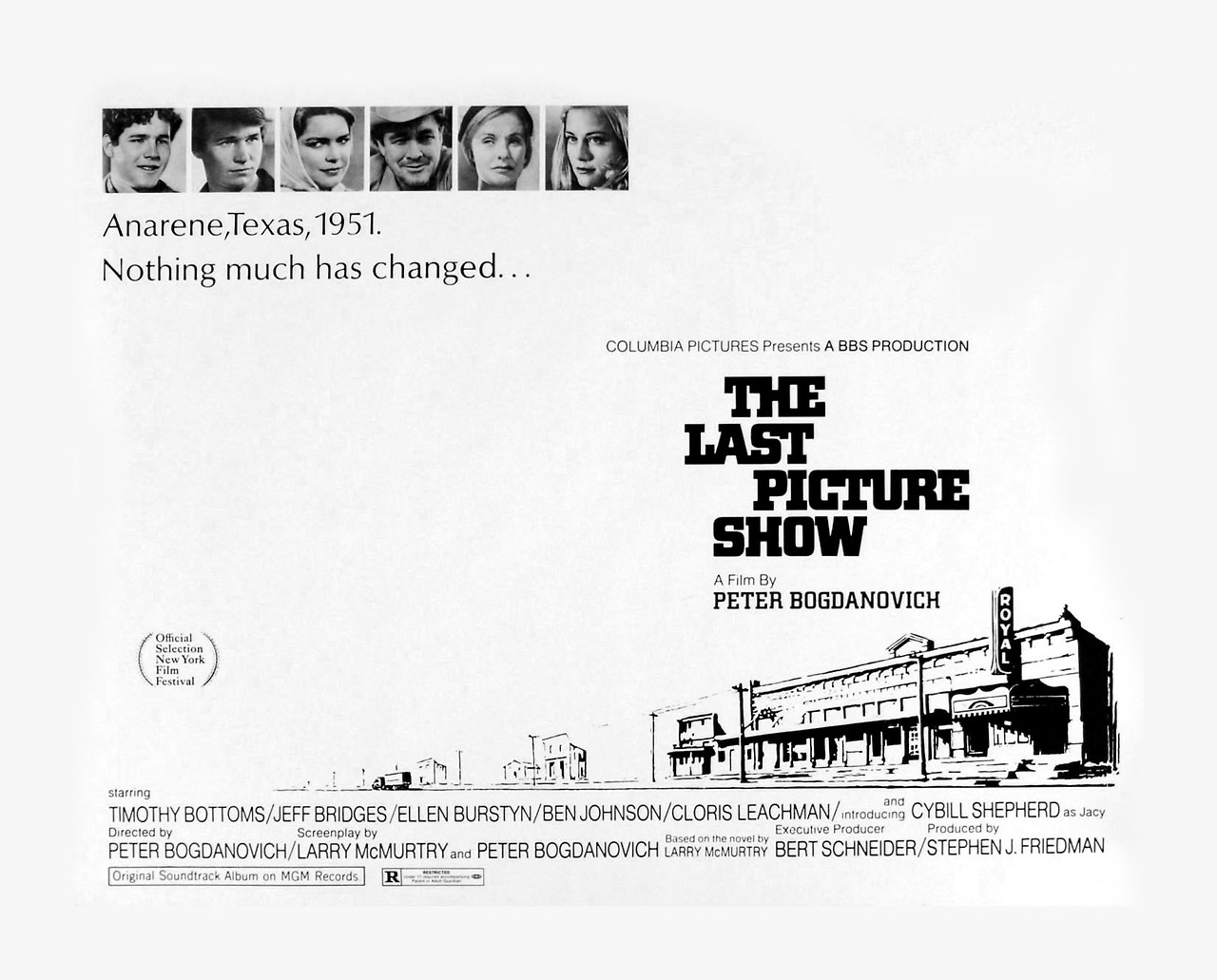

‘The Last Picture Show’

“The Last Picture Show” (1971) was the first critical and commercial success for the then-young Hollywood wunderkind Peter Bogdanovich. More so than some of his later efforts, it boasts impressive control of the touching, bittersweet narrative and an ability to bring out the best in his outstanding ensemble cast — many first or second-time actors (Jeff Bridges, Cybill Shepherd, Timothy Bottoms), and well-cast mature stars (Ben Johnson, Cloris Leachman, Ellen Burstyn, and Eileen Brennan).

As director/screenwriter, Bogdanovich had the advantage of using as his framework an early novel by Larry McMurtry (who went on to win a Pulitzer Prize in 1985 for his revisionist western epic, “Lonesome Dove”). McMurtry’s story itself, a coming-of-age slice of life — teenagers often in over their heads in suspect adult morals — was an autobiographical novel based on his formative years growing up in Archer City, TX, a small town 40 miles northwest of Fort Worth. It is the book’s none-too-thinly disguised setting and the location of the film itself.

Although in some ways it appears a love letter to his home town, the novel is also a young writer’s unsentimental, often caustic critique of what it was like to grow up in a then-isolated and resource-poor small Texas town in the early 1950s. Both aspects of the book are so evocative of its time and place that the making of the film became a careful exercise in capturing its characters and moods, a challenge which Bogdanovich met with skill and intelligence.

McMurtry, although listed as co-screenwriter, lost interest early on when the director resisted his attempts to rewrite his own key scenes. Where McMurtry saw the opportunity to revise and change, Bogdanovich insisted on fidelity to the original source.

In comparing the book to the film, each character is seamlessly inhabited by the remarkable cast. Set to a strictly period soundtrack of plaintive Hank Williams country western songs, the young ensemble acts out their loyal friendships, romantic longings, and petty jealousies. They also portray their confusing collisions with the inequitable structure of the outside world about them and the sexual frustrations of the generation before them. For instance, Jacy Farrow (Shepherd), the beautiful girlfriend of Duane Jackson (Bridges), is, in actuality, trained by her promiscuous mother to be a callous and manipulative social-climber. Sonny Crawford (Bottoms), living apart from his alcoholic father, falls into a misbegotten affair with a lonely housewife twice his age (Leachman), with heartbreaking results.

For the film, Bogdanovich, a former cinema scholar, carefully studied and applied lessons from his idols Orson Welles, John Ford, and Howard Hawks. From Welles came the decision to film in black and white. Welles advised the director that rather than color, only a monochromatic palette would provide the needed abstract distance, a device that provided the film its stark and elegiac look. “Also,” he added, “actors’ performances always look better in black and white!”

And Bogdanovich shrewdly drew on Ford and Hawks for the two astonishing set pieces in the film, performances for which two of the older actors won Academy Awards. In the first, a long soliloquy with Sonny and friends by the lake, Sam the Lion, the town’s de-facto father figure (in the absence of any other responsible parents), describes with nostalgia and regret his long-ago affair with a then-young local girl, whose identity is only revealed later in the film. As Sam (Ben Johnson, a syrup-tongued John Ford alumnus) speaks in a long, single take, the sun appears at a crucial moment from a cloudy sky — a true unscripted Ford moment.

In the second piece, a concluding confrontation between Sonny and Ruth (Sonny’s rejected older lover), Leachman delivers a devastating emotional diatribe over an intentionally distracting background, Hawks-like overlapping dialogue of an old comedy routine, on a radio that Ruth neglects to turn off. This competing noise forces the viewer to focus and strain in order to appreciate her remarkable tirade, her cry of despair at the asymmetric relationship which she has initiated but from which she has been excluded. The young Sonny, guilt-stricken, bereft and alone, can only listen without responding, yearning for the absolution which finally, exhausted, she gives: “Never you mind, honey . . . never you mind.” Two deserved Oscar performances.

It was not easy to produce the movie in this only-too-real on-site location. McMurtry’s mother, still living in the town years after the revealing novel was published, had to endure again the approbation of her fellow townspeople (her next-door neighbor was still not speaking to her). Bogdanovich was a Hollywood outsider to this small town (one grizzled local remarked in a later interview, “with a name like Bogdanovich, I knowed he weren’t from Wichita Falls.”)

And Bogdanovich himself, when the shooting began, was married to Polly Platt, the film’s talented production designer. However, halfway through the schedule, he began an affair with Shepherd, the former model who he had hired to play the flirty, pouty Jacy. In later interviews, Platt was revealed as the glue that held the production together, even in the face of her disintegrating marriage. It’s a miracle the film was completed, let alone at the high level of professional quality and emotional impact that resounds today, over 45 years later.

P.S. If you have an itch to find out what happened to Jacy, Duane, Sonny, Ruth, etc. as they made their way through life, you may be tempted to read “Texasville” or even “Duane’s Depressed,” Larry McMurtry’s two sequels in what he called the “Thalia Trilogy” (after his alias for his Archer City home town).

Breeze through them if you wish — unlike the bleak and unsparing original novel (which you must read), they are McMurtry in his later raucous and inconsequential mode. But by no means bother to see Bogdanovich’s mistaken filming of “Texasville” (1986), in which he brought back Bridges, Shepherd, Bottoms, Leachman etc. for an awkward, poorly adapted, and pointless exercise, revisiting its classic predecessor.

“Streaming” is a periodic look at classic films, available on home networks and apps. “The Last Picture Show” is currently available on iTunes, Amazon, VUDU, and FandangoNOW.