Hal Hartley, Long Island Existentialist

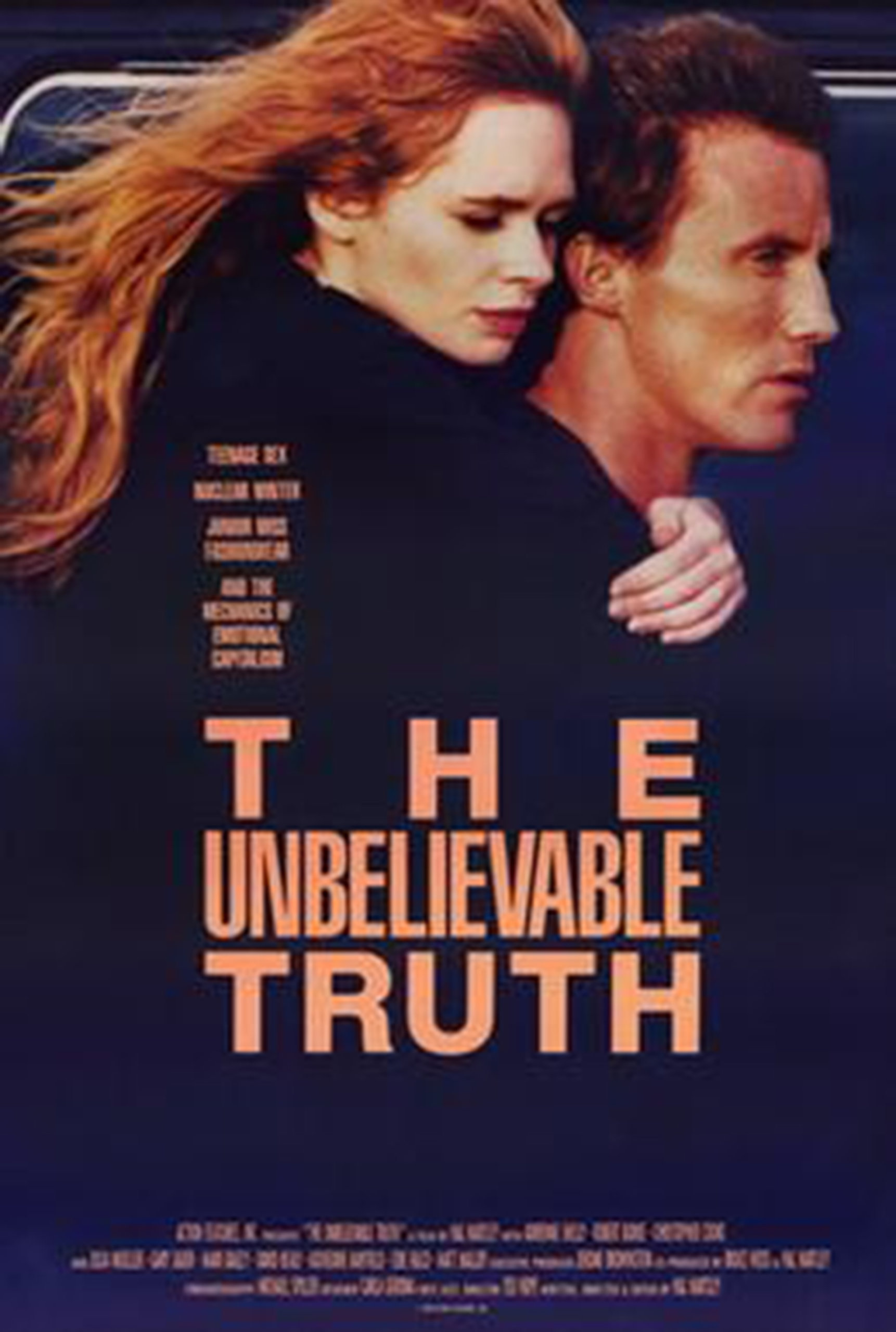

Paris, 1992, and banners over the Boulevard Saint-Germain announce the “Hal Hartley Festival du Cinéma,” featuring his early films such as “The Unbelievable Truth” (1989) and “Trust” (1990). Hartley was already a New York art house and film festival cult figure, but who knew that this Long Island-based filmmaker had been adopted by the most passionate French cinéastes as one of their own? Watching Hartley’s deadpan, humorously listless dialogue reproduced in French subtitles to Gallic murmurs of audience delight, one realized his quirky screenplays are being recognized by the newest of New Wavists as true avatars of l’Existentialisme.

Tip: today you can experience that same frisson of erudite discovery by streaming one of these engaging films (not easy to find, but see below), turning on the closed caption button for (albeit English) subtitles, and absorbing the faux-melodramatic dialogue by eye as well as ear. Enjoy it maybe with a shot of Pernod, but definitely a can of Rheingold beer on the side. After all, these films take place in faceless neighborhoods adjacent to the ubiquitous LIRR viaduct.

Hartley is a Long Island-raised director/screenwriter, a true auteur. His ironic personal style infuses almost 20 films, and has had an influential impact on a generation of later independent directors. Especially in his early films, his characteristic, punkish sense of anomy is reinforced by his local settings of choice, in this case his native Lindenhurst, a working-class community — “fly-over country,” as described by a snobby Hamptons/Manhattan acquaintance. But you could be in any anonymous venue —Jim Jarmusch’s highway exurbs (“Stranger than Paradise”) or Antonioni’s industrial wastelands (“Red Desert”).

What really sets Hartley apart are not only his idiosyncratic screenplays but the talented casts he assembles to bring his characters to life. As a prime example, Adrienne Shelly, the fresh-faced young actress whose blank readings of extremely funny dialogue earned her a place in many future Hartley ventures, eventually became a filmmaker in her own right. (In 2006, she was tragically murdered by a burglar in her Manhattan apartment, right before her final directed film “Waitress” opened to critical acclaim).

In “The Unbelievable Truth,” Shelly plays Audrey, a young girl who spends her time arguing with her auto-mechanic father (Chris Cooke, in a memorably spluttering performance) about whether to apply to Harvard or pursue her obsessive anti-nuclear advocacy. (She eventually takes a job as a fashion model.) Spurning her various loutish school and neighborhood companions, she falls in with Josh (Robert Burke), a lanky, taciturn, mysterious drifter who hitchhikes into town. He has recently been released from prison, an admission that makes it hard to get rides. Dressed in black (a running joke: “Are you a priest?” “No, I’m a mechanic”), he takes a job in Audrey’s father’s auto shop, where they meet and develop an offbeat friendship.

Josh was implicated in a local killing years before, but in spite of this murky past, he falls back in with his old crowd (“Things happen. People make mistakes.”) One of his old friends, a loose local waitress (Edie Falco, in her pre-Carmela Soprano days) tries to ignite a liaison, but is rebuffed. John is a loner and celibate. But “The Unbelievable Truth,” it turns out, is that Josh was not guilty, much to the relief of Audrey and the confusion of her neighbors.

“Trust,” the follow-up film produced the next year, takes its title from an incident in which Maria (Shelly again) does a spontaneous, unexpected back flip off a six-foot concrete wall into the arms of her astonished, but luckily alert boyfriend, just to prove her point that the mark of a true relationship is whether you trust each other, especially in unexpected circumstances.

As this second film begins, she announces to her parents that she is quitting high school to get married, and by the way, she is pregnant. This news catapults her father into cardiac arrest, and her mother kicks her out of the house. From this point on, the film becomes an absurdist soap opera, peopled by Maria’s strange friends and family: her football player boyfriend who jilts her on learning of her pregnancy (it will conflict with his non-existent future NFL career), her bored divorced sister (Edie Falco again), her seriously depressed and manipulative mother, but especially Matthew, another tall, black-dressed stranger (this time Martin Donovan), a mop-haired mechanical genius whose perfectionism and anti-establishment obsessions prevent him from leading a normal life.

Matthew lives with his tyrannical father (“Clean that toilet again!”), a weirdly comedic turn by John McKay that turns nasty. Matthew’s and Maria’s odyssey (after he unsuccessfully proposes marriage to give her unborn child a chance) goes in weird circles and ends up more or less where it started, with the entire cast (untrustworthy to the core) negatively illustrating the title theme, and Maria helplessly watching the ever-neurotic Matthew shipped off to an asylum.

The production values in these early Hartley films are surprisingly high given the shoestring budgets with which they were made. (The first film was initially financed with a $6000 computer equipment loan.) The cinematography in each film, by John Stiller, a SUNY Purchase film classmate of Hartley’s, is spare, washed-out, and deliberate — in other words, a perfect match to the screenplay. The similar soundtracks (by Jim Coleman and Philip Reed), featuring unexpected crescendos and diminuendos, also match the punk-like mood of the stories.

Maybe not for everyone, but who knows? For the viewer who will revel in the beneath-the-boredom dialogue, the deadpan acting styles, the knowing afternoon TV serial cheesiness of the script, Hartley’s films are an addictive treat that will leave you searching for more examples. And for the existentialists among us, Hartley’s French enthusiasts had discovered something: an absurdist vision of middle-class Long Island that is an American version of Sartre —No Exit, indeed.

Streaming is a periodic look at classic films, available on home networks and apps. “The Unbelievable Truth” and “Trust” are currently available on Amazon, iTunes, and TUBI.