Homosexuality In Mid-Century America

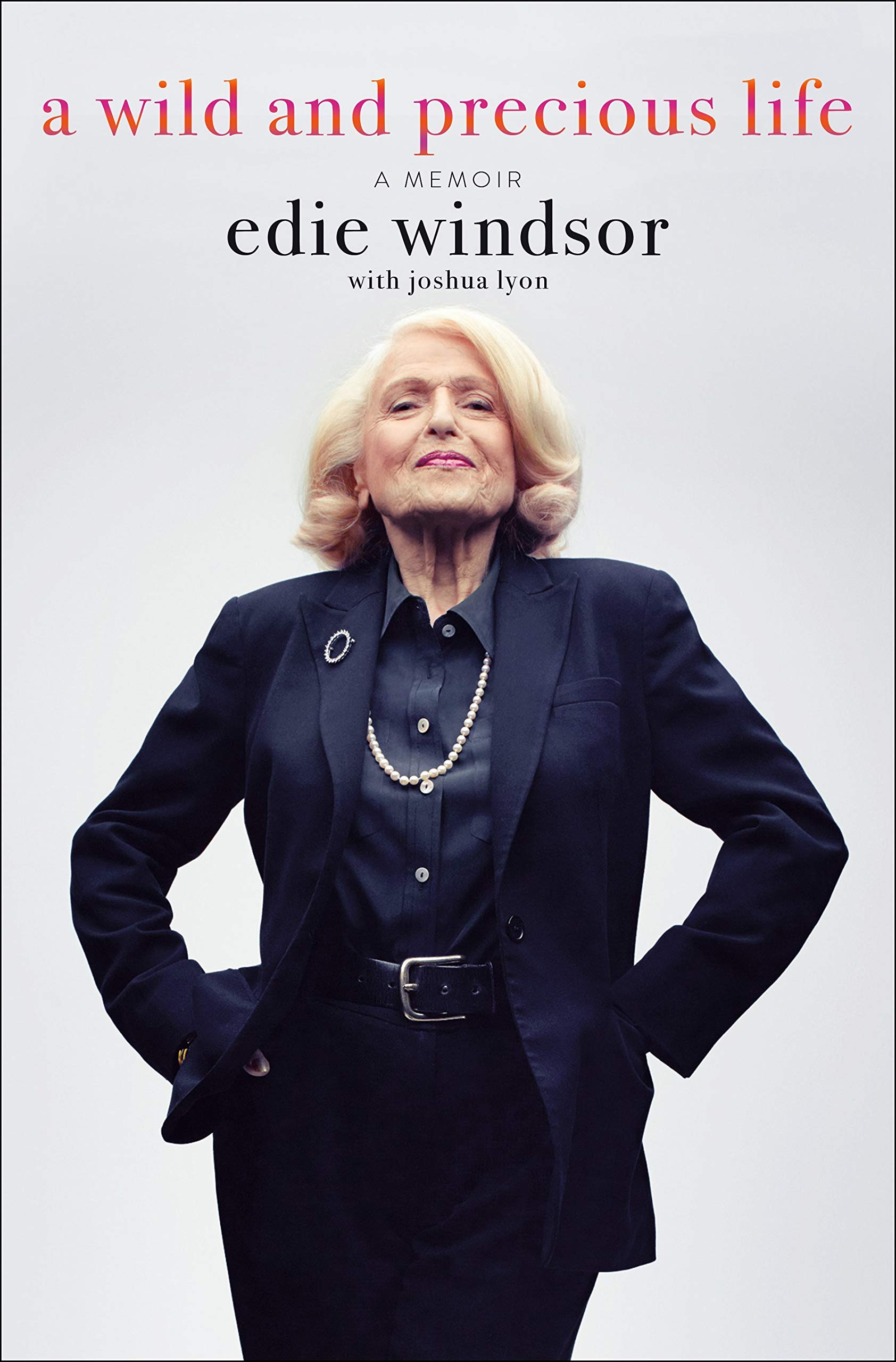

“How had I gone from a woman so deeply concerned about making sure my coworkers hadn’t known I was gay, to suing America because of it?” said still amazed Edie Windsor (1929-2017) a few years after her 2013 win at the Supreme Court in Edith Schlain Windsor v. The United States, which struck down federal law banning recognition of same-sex marriage, and opened the way for lawsuits challenging state bans. The case, which she threw her head, heart, soul, and aging body into, is part of a wider, deeper, fascinating, and well-written story about the gay rights movement in this country which Windsor tells in “A Wild and Precious Life.”

The title is taken from the poem “A Summer Day” by Mary Oliver (herself gay), an exhortation to seize the moment. It was quoted by an admiring Hillary Clinton at Windsor’s eulogy.

The memoir is more than a captivating recollection of one individual’s painful attempts to belong and be loved, to deny and then fight. It also describes an era and is thus invaluable as cultural history. Did we know how tight the connection was between gay bars and the Mafia? Or how coming out was abetted by serving in the military?

With an eye mainly on accepting and legitimizing lesbianism, but also embracing the cause of gay rights for all, “A Wild and Precious Life” recreates what life was like for homosexuals in mid-20th Century America, in Greenwich Village and in the more upscale and sophisticated Hamptons (so different from the Stonewall crowd). In Southampton, a popular meeting place was Fowler’s Beach.

Though the memoir begins with Windsor’s happy childhood in Philadelphia in a non-observant middle-class Jewish family, the narrative becomes an ambivalent account of love and loneliness, of bar hookups and secrecy, after she comes to New York to look for personal and professional identity. She even invents an imaginary boyfriend, “Willy.” It was the time of the Communist witch hunt, but also of the “Lavender Scare,” especially after HIV took hold and took lives.

As Windsor herself said, however, she wanted to be remembered for two reasons: her work as a seminal figure fighting section three of the Defense of Marriage Act, and her career as a mathematician at IBM, where she was the first woman to be a senior systems programmer and the first person to get a PC in recognition of her groundbreaking work on computers. Her expertise with numbers, which she loved, even paid off in casinos, where she won big by counting cards.

Eventually Windsor put her two worlds together as a pro-bono consultant for, among others, Lesbians Who Tech and Services and Advocacy for GLBT Elders, the latter fueled in no small part by the 44-year relationship (including, finally, marriage) she had with the love of her life, Dr. Thea Spyer. Spyer, of Dutch Jewish heritage, was two years younger, a clinical psychotherapist, and an accomplished violinist. She died from multiple sclerosis in 2009. Both women, beautiful, bold, brilliant, and regarded as great dancers as well as “heartbreakers” in their set, met their match in each other.

Their dynamic, sensual, affection-filled relationship, recalled in the prize-winning film “Edie and Thea: A Very Long Engagement” (2009), constitutes one of the most engaging — and moving — expressions of love, regardless of sexual preference, found in contemporary memoirs. And a reminder, as Windsor says, that you can be “hot” at any age. For sure, those two were, even after Spyer was in a wheelchair.

“Something of a memoir/biography” better describes “A Wild and Precious Life” says co-author/journalist Joshua Lyon, who was interviewed by Windsor for the job of assistant toward the end of her life, and who devised an effective way to integrate her voice and his (his is set in italics). He provides timeline details and updates, chapter by chronological chapter, and emphasizes by way of follow-up interviews and research Windsor’s evolving attitude about coming out and becoming an activist. Sensitive to her wishes, Lyon acknowledges changing a few names and not dwelling on her contested will.

Her archive of materials was extensive. Windsor was an obsessive record keeper and chronicler about what she later came to see as fruitless attempts to pass: “I liked boys, I really did,” she says early on. She went on dates, mainly to please her mother, even marrying Saul, a close friend of her adored brother (it lasted for six months). Saul, who had agreed to change his name from Wiener to Windsor changed back again after the divorce. She, with her eye on career, did not.

It’s quite a story. Windsor was Grand Marshal for the NYC LGBTQ Pride March in June 2013, and this year Stony Brook Southampton Hospital named its HIV/AIDS center after her. For certain, hers was a life that was wild and precious and memorably instructive. The pics are great.