Preserving the Memory of Those Lost at Sea in Montauk

You place your hands on the stone. Close your eyes. Let your fingers feel the grooves cut into the smooth rock. Listen as the sound of the water crashing below and the wind whipping up and off the waves rises. Now you open your eyes and stare out.

Fishing boats dot your field of vision. Four or five are just offshore, others further on, some barely specks on the horizon. Heading out, they share the singular mission of hauling their catch and returning home safely. And the same uncertainty of not knowing if they will.

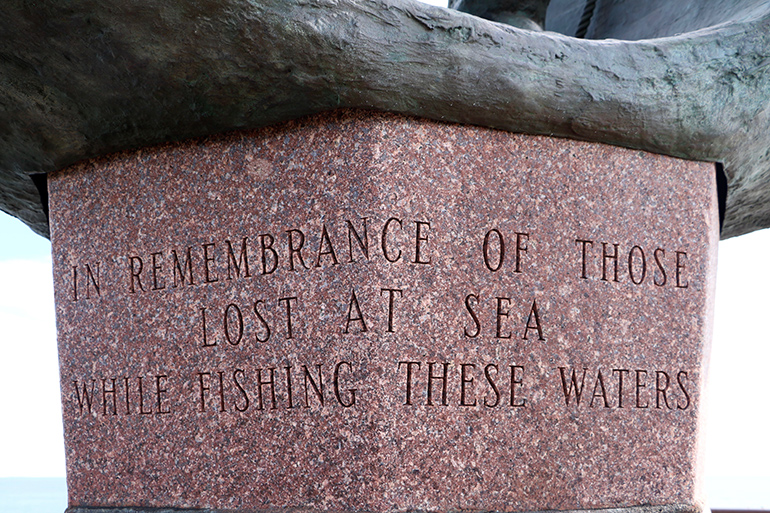

You reach this vantage point walking up the hill to the Montauk Lighthouse, then beyond it, almost as far as you can go before a fence keeps you from the precipice of the cliff that falls off the easternmost point of Long Island. There, depending on the light, either in the shadow of the famous beacon or in a bath of sunshine all its own, stands the Lost at Sea Memorial.

Any number of emotions arise when you encounter it, the means to describe it proving difficult to come by immediately, until Montauk Lighthouse Historian Henry Osmers utters a single word.

“Poignant.”

It rises up 15 feet, an 8-foot bronze sculpture resting atop a 7-foot granite base. Standing closer to the cliff’s edge than the lighthouse itself, a soaring and sobering reminder of just how tenuous the relationship is between fishermen and waters that both provide a living and claim life without warning. Commercial fishing is one of the most dangerous professions on earth, and the memorial, and this Sunday’s October 20 ceremony honoring the 20th anniversary of its completion are a reminder of how closely that danger hits home and how many lives it touches.

Given the history of fishing here on the East End, a proud tradition woven as deep into the collective past as any other, it may be something of a surprise that the memorial was erected only two decades ago. The idea arose in the early 1990s from a group of fishermen and families who had lost friends, husbands and loved ones at sea and felt the moment had come to create a lasting symbol of honor and reverence.

Amid efforts to raise funds and interest, a contest was held to create a worthy design, and Montauk artist Malcolm Frazier’s vision was chosen: a single fisherman, who for eternity will stand alone in his boat, proud and tall against weather and what may come, pulling his line from the sea. He is not any one of the individuals on the granite below, but all of them, and countless others who never came home.

Dedicated in 1999, the memorial contains some 120 local names. They perished in the infamous Pelican wreck of 1951 and the Wind Blown tragedy of 1984, during the Hurricane of 1938 and unknown storms through the centuries. Into the granite they are cut, their age and the date when they died, all the way back to 1719. Some have surnames that have written the history of the East End, others are remembered by just a single name (“Dick”) or even simply “Captain Clarke’s Son.” Teenagers, veterans of decades on deck, the sea does not discern.

There was some debate as to where the memorial would ultimately be placed, Osmers notes, with one faction feeling it belonged in the harbor, from which so many fishing journeys have begun and ended. But its final home “really is fitting,” he notes, as it gazes out not just into the nearby waters but into the endless ocean beyond to honor “East Enders, fishermen who are from here who have been lost at sea, not just in these waters, but anywhere out there.”

Wherever they have been lost, they have had no burials, there are no gravesites. But there is a place to mourn, to find solace. The Lost at Sea Memorial stands as a reminder, a touchstone, a place of reflection and never forgetting.

“One woman I remember, she came from out west, she must have been in her 80s, they helped her from her car to get all the way up here,” Osmers recounts. “Her son was one of those who’d been lost, and she wanted to come all the way here just to touch it. It was something tangible for her, and that’s the best word I can use to describe what it is. It’s tangible.”

Place your hand on the names. Close your eyes. Open then and look to the sea. Remember.

The Lost at Sea Memorial 20th anniversary ceremony takes place on October 20 at 3 p.m. at the Montauk Lighthouse. The event is open to the public. For more information, visit lostatseamemorial.org.