The Ghosts Of Halloween

Almost every Irish family has a ghost story.

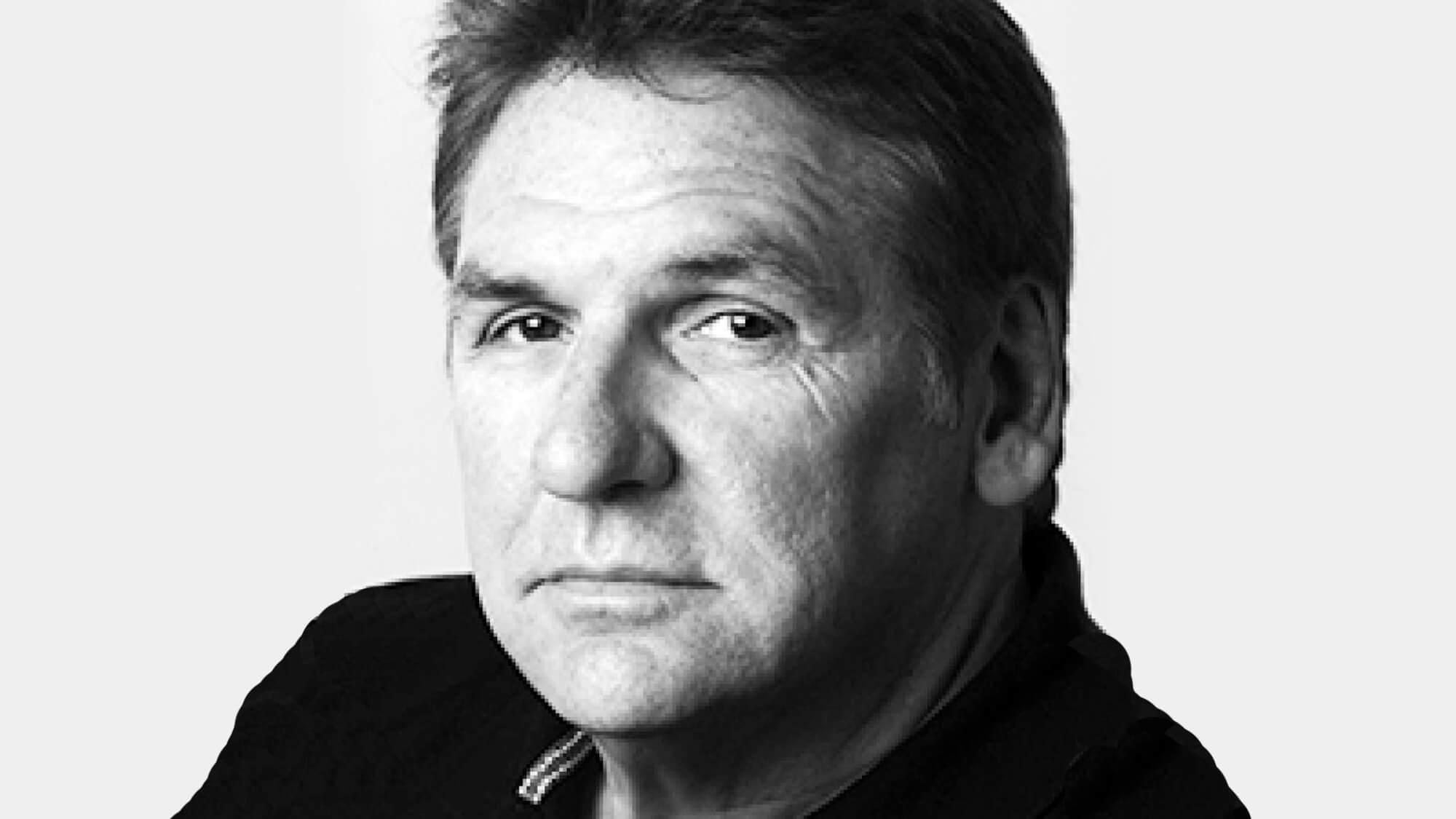

My down-to-earth father Billy Hamill was the last guy you would ever think believed in ghosts. But every Halloween, as the tales of the macabre, the occult, witches, vampires, and spook houses echo through the East End, I am haunted by my father’s ghost story.

To put his real-life ghost story in perspective, we must start where Halloween has its origins, in that foggy land of misty bogs and wailing banshees and “little people” who protect crocks of gold at the end of the rainbow in Ireland.

Samhain is the ancient Celtic pagan festival at summer’s end after the harvest when people would light bonfires and wear scary costumes to ward off the cold and wicked spirits of winter. In the eighth century, Pope Gregory III designated November 1 as a time to honor All Saints Day, therefore subsuming the pagan traditions of Samhain on its eve of October 31 as All Hallows, where people were encouraged to dress as long-dead saints to scare away the evil spirits of the devil.

At Christmastime, back in the 1970s, I visited the splendid Carrick on Suir, Co. Tipperary farm of Paddy Clancy of the storied Clancy Brothers traditional Irish music folk group. Before St. Patrick escaped as a Roman slave from England to Ireland and spread Catholicism to a pagan land, December 26 was a day when costumed men used the carcass of a dead wren to chase away the evil spirits of winter. The Church would soon appropriate this Celtic tradition and call it St. Stephen’s Day.

But when I visited Paddy Clancy, deep in the countryside of Tipperary, his family revived the pagan “Wren Boys” tradition on December 26 the same way they had revived traditional Irish music in Ireland. Paddy and his brothers Tom, Liam, and Bobby and their visitors dressed in crazy costumes as pagan Wren Boys, who, in times gone by, would catch and sacrifice a singing wren and wrap the poor bird in colored cloth and run wild through the fields to chase away the evil spirits.

As it became a Catholic holiday, the costumed kids would go to the doors of neighbors begging for pennies and singing “The Wren Song” which the Clancy Brothers recorded:

The wren, the wren, the king of all birds

St. Stephen’s Day was caught in the furze

Although he was little his honor was great

Jump up me lads and give him a treat.

Up with the kettle and down with the pan,

And give us a penny to bury the wren

My father was born into this haunted land where the Catholic Church transformed Samhain into All Hallows, aka Halloween. He was raised in Northern Ireland, in Ulster, in the tough, industrial city of Belfast in a family of 11 children. His father, David, was an iron molder who had a hard time finding steady employment because the Hamills of 44 Locan Street were Roman Catholics in a predominantly Protestant town ripped apart by revolution, partition, and sectarian bigotry.

My father grew up playing soccer, a center forward on the rocky pitches of West Belfast, dazzling people with his speed, feints, and ball-stealing skills. His first cousin was Mickey Hamill, considered the greatest professional footballer of his era as a wing half for Belfast United, leading Ireland to its first Home Championship Win, even defeating England in 1914. Mickey Hamill would later play for legendary Manchester United and was lured with American dollars to play for immigrant teams in Boston and New York.

My father left Belfast in 1924 hugging and kissing his siblings farewell, especially his most beloved older sister, Kathleen, whom he promised he would one day see again. My father crossed the Atlantic in ratty steerage, moving into a rooming house in Brooklyn. He boxed for speakeasy money and played soccer for a variety of immigrant teams that were so popular, profitable, and competitive in the 1920s.

Then, on March 25, 1928, on Commercial Field in Brooklyn, when he was playing for St. Mary’s semi-pro immigrant soccer team against a famed Jewish immigrant team called Hakoah, my father was blindsided with a ferocious slide tackle that broke his left leg, bone piercing flesh. In a time before penicillin, as my father waited hours on the sidelines for an ambulance from Kings Country Hospital a mere half-mile away, sepsis set in.

That night, my father recounted years later, he was told that he would have to have his left leg amputated above the knee. This single nightmare shattered all his American dreams. Or so he thought. He was given morphine for pain, and as he awaited the surgery a little before midnight, he wondered what his life would be like after losing a leg at 24. He would never again box or play soccer. He wondered if he’d ever dance or marry or have a good job and an American family of his own.

“Then I was startled to see that my beautiful sister Kathleen had come to visit me,” my father would later say. “I hadn’t seen her since I left Ireland and I’d heard she was sick. But here she was for me. Holding my hand and telling me that everything was going to be just fine. That I would meet a wonderful woman and have a big family and many sons and a long life.”

She was right — Billy Hamill would live a longer and happier life than his superstar cousin Mickey Hamill, who would later return to Belfast where he married a woman he adored but suspected of infidelity. On July 23, 1943 Mickey Hamill’s body was found floating in the River Lagan, declared a suicide.

But back on that fateful night in Brooklyn in 1928, Billy Hamill’s sister Kathleen kissed her younger brother before he was wheeled into surgery where doctors would saw off his left leg.

The next morning, when my father awoke in post-op pain and the cruel reality of dawn missing a leg, he realized that he’d only had a morphine dream about his sister Kathleen visiting him the night before. Then a messenger arrived at his hospital bedside with a telegram. It was from his twin brother Frank in Belfast informing him that just before midnight the night before Billy Hamill’s most beloved sister Kathleen had died peacefully in her sleep.

“On her way to Heaven my sister Kathleen stopped by to visit me,” said my father. “So yes, I believe in ghosts because Kathleen sat on my bed and held my hand and promised me that everything was going to be okay.”

Two years later, Billy Hamill met Annie Devlin at an Irish affair that led him and his wooden leg onto the dance floor and then to the altar. They had seven kids, six sons, and a daughter who was born on Billy Hamill’s birthday, whom he named Kathleen.

My father died at 80.

Do I believe in ghosts? Well this story appears to me every year with the fulvous leaves of Halloween that haunts us all from the smoky bonfires and singing Wren Boys of Samhain in a mystical place called Ireland where Halloween had its Celtic ghostly origins and so did my father who is long gone but still here with me.

Yes, Kathleen, I believe in ghosts . . .

denishamill@gmail.com