Mile-a-Minute Murphy: Cyclist Attempted to Keep Up with LIRR Locomotive

This is the story of Mile-a-Minute Murphy. It’s a remarkable tale. And it happened on Long Island.

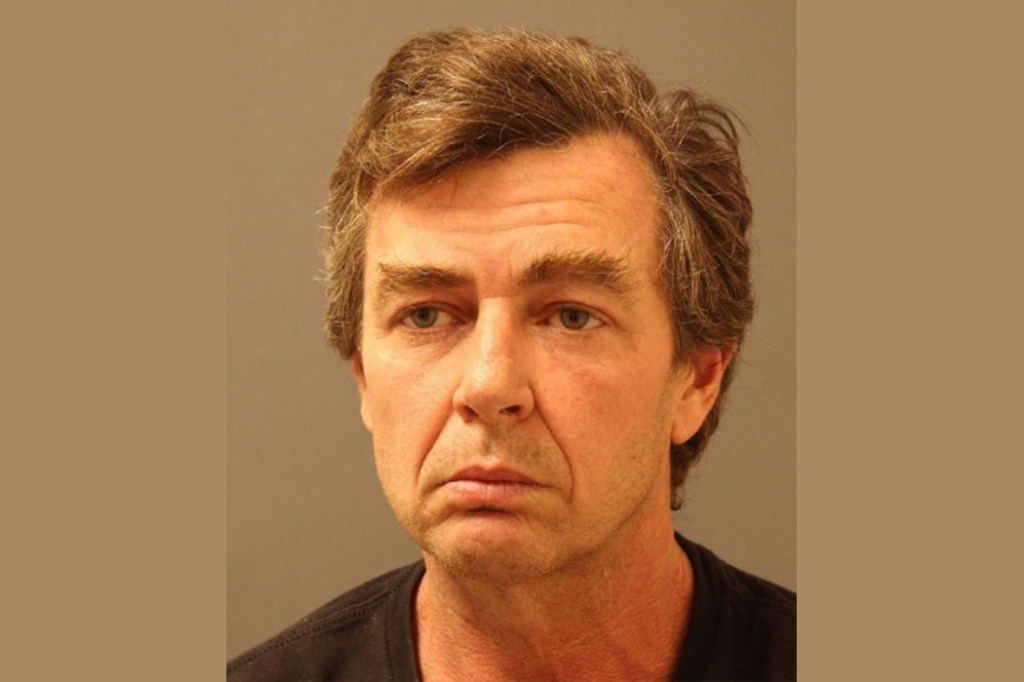

Around 1890, Charles Murphy of New York City got it in his head that he could ride a bicycle for a mile in a minute. He told his friends about it and they laughed at him. No one had come close to doing it. Murphy at that time was 20 years old, five-foot-seven and 140 pounds of lean muscle.

During this era, bike riding was all the rage. The first automobiles were built. In the whole country, though, there were only a few thousand. But there were millions of people on bicycles. The railroads had given the populace a taste for travel. Bicycles were now the way to go from place to place nearby.

Three-speed bikes had not yet been invented. All bikes in Murphy’s era were single-speed. So the idea of flashing along at 60 miles an hour for a mile seemed preposterous. Even the fastest bike riders in various races around the country—and Murphy participated in some of them—could get up to 30 miles an hour, maybe 40, tops. Murphy had theorized that if he could pedal his bike in the draft behind a railroad train, he could do a mile a minute, or even more. The sky’s the limit, he said. A man can do anything.

Murphy may by this time have heard the legend of John Henry, the steel driving man. In 1840, Henry worked on the B&O Railroad in West Virginia. The boss had this new machine. It would put the men out of work. Instead, they held a race, man versus machine, to see who could drive the most steel into the rock inside the Big Bend Tunnel. Henry fell behind at first, but then surged ahead and won. But then, exhausted, he had a heart attack and died.

One day, Murphy told his idea to a group of people at Howes Roadhouse near his home. Among those there was Hal Fullerton, a special agent for the Long Island Rail Road, which, in 1896, had finely laid tracks out to the Hamptons and Montauk. Amidst the laughter, Fullerton stepped forward and said he might be able to arrange for Murphy to try.

Fullerton got permission to take over a two-mile straight stretch of track across some farmland out in Babylon, which was then part of a hundred-mile stretch of farmland leading out to Montauk Point. He had workmen build smooth planking between the rails. Then he brought in a steam locomotive with a single caboose behind it and set it up at one end of this two-mile stretch. The back of the caboose had been fitted out with two metal side panels. It was expected that Murphy would ride on the planks and be safe from the wind between these two panels as the locomotive cranked up to its top speed of 60 miles an hour plus.

A huge crowd came out to watch. The date was June 21, 1898. There were photographers and newspaper reporters. The signal was given and the steam engine blew out smoke and began chuffing forward, with Murphy pedaling between the panels behind.

During that first mile the locomotive slowly lurched toward its top speed. The stopwatches were clicked on when the train started that second mile. Murphy pedaled furiously.

Elapsed time at the end? 1:08. A mile at 57.3 miles an hour. The effort had failed. Murphy seemed hardly winded. He said let’s do it again. The second time the readout was to 56.7 miles an hour. Again, said Murphy. 58.3 miles an hour.

Interestingly, at the same time Murphy was doing this, another bike rider, Eddie McDuffie, was making the same attempt behind a train up in Boston. But he could pedal at only 46 miles an hour and gave up.

Murphy tried it two more times, and still could not achieve a mile a minute. Fullerton felt even worse with all this effort. But then he realized that the locomotive simply was not strong enough. They’d try again a few days later, and Fullerton would have another locomotive.

This time, on June 30, Murphy experienced a vastly superior surge by the locomotive. It went faster and faster, Murphy for a moment falling back 50 feet. But then, with a superhuman effort, he pedaled his Tribune Blue Streak back into the draft and stayed with it. The engineer saw the end of the wooden boards approaching and turned off the steam, slowing the locomotive quickly and sending Murphy and his bike forward over the railing and then head-over-heels into the caboose and into the crowd of officials, including Fullerton—a fact that probably saved his life. Final read. 57.8 seconds. 61 miles an hour. He’d done it.

The New York Times wrote, “[Murphy] drove a bicycle a mile faster than any human being ever drove any kind of machine and proved that human muscle can, for a short distance at least, excel the best power of steam and steel and iron.”

Murphy was now Mile-a-Minute Murphy. He toured the country, then settled back down in Queens to spend the rest of his life as a policeman. He was commended four times, cited five times, married, widowed and married again. When he was in his 30s, he was thrown off his motorcycle while chasing down bad guys in a touring car, which ran over his legs. Injured, he nevertheless dusted himself off and continued on. In a second accident, he hurt his back, and finally, in a third, he fractured his knee, which ended his bicycle-riding career. He lived to be 79, passing away at home. A tough man.

Murphy’s mile-a-minute record lasted 30 years! It was finally broken, then broken again on September 18, 2018. The new record for the mile was set on the Bonneville Flats in Utah by a rider wearing a pointy helmet and goggles and riding a multi-gear racing bike while drafting behind a jet car. Her name is Denise Mueller-Korenek, and she went 183.932 miles an hour.

But it all began with Mile-a-Minute Murphy.