Billionaire Fights to Make Public Road Near His Springs Property Go Away

David Buda is a retired attorney living in The Springs with his wife, a professional artist. He has taken on the role of town watchdog. He goes to town board meetings, he attends gatherings of other town committees and boards, and he keeps an eye out for things that appear to not be right.

Every town needs this kind of watchdog. But not all towns have one. It should be a job, perhaps an appointed job, in the same way that every town is required to appoint a town historian.

Last year, Buda participated in several town board hearings about a proposal put on the table by representatives of billionaire Michael Novogratz, a former hedge fund manager and now crypto-currency exchange company owner. In 2016 Novogratz and his family bought the 33-acre Francis Fleetwood estate on Ocean View Lane, Amagansett, reportedly for over $14 million through an LLC. In 2018 an LLC also purchased a five-acre parcel on Cross Highway for $3 million, which is adjacent to an unpaved section of that highway on one side and the Fleetwood property on the other. Buda has contended that the property owner has intended to move the old Fleetwood home to the smaller parcel so he could presumably build a mansion more to his liking on the larger parcel.

The proposal from Novogratz’s lawyer that was debated last year was whether the Town would agree to “abandon ownership” of the adjacent unpaved road and have the Town accept a trail easement over the road in exchange. If the Town agreed to do so, Novogratz’s lawyer told me, the addition to the smaller parcel would enable Novogratz to move the Fleetwood home there without a variance.

The lawyers for Novogratz didn’t offer money in exchange for abandoning this road, but only proposed the Town get a trail easement. Because the trail was within the boundaries of the Town road, the Town did not need an easement for the trail. The request was denied, and the matter seemed to have been put to bed last September.

Then came this summer. There were some indications that things may have been brewing.

“Some people suggested I should look into this again,” Buda told me last week. “I went to town offices. There was nothing new about the Fleetwood property, but I found there had been two very unusual deeds recorded in March involving Novogratz’s five-acre parcel.”

Buda told me he went to Riverhead where the County keeps the official records of property transactions, to review all deeds in the chain of title.

“The first deed recorded this year by Novogratz’ attorneys substitutes for a 2005 deed given to a prior owner. The original 2005 deed, consistent with an earlier 1938 deed, includes a detailed metes and bounds survey description that clearly indicates that a town highway exists on the western boundary and it is excluded from the land conveyed. This substitute deed denies the existence of that town highway and makes it part of the land transferred by the deed. It tries to justify making such a radical change in the 2005 deed by ‘confirming’ that a certain 1921 deed is accurate.

“However, it is this 1921 deed that is in fact erroneous, because it fails to acknowledge the creation of the town road in 1914,” Buda said. “This 1921 deed is the singular deed in the half dozen or so chain of Deeds that fails to recognize the existence of the town highway. It sticks out like a sore thumb. All the other deeds in the chain after that—the next was in 1938—correctly state that Cross Highway exists and is the western boundary of the five-acre property.

“Here’s the rather fantastic language used: ‘The metes and bounds description contained in the Suffolk County Tax [Sale] Deed recorded in [1938] was inadvertently changed [and] thereafter all intervening conveyances mirrored the erroneous tax deed description.’ With this language, I believe Novogratz hoped the existence of the roadway, and the exclusion of the highway land from all relevant conveyances, could and would be disregarded.

“The second new 2019 deed replaces the legal description in the 2018 deed that transfers the five-acre parcel to Novogratz,” Buda continued. “It is labeled a ‘Correction Deed.’ If the two new deeds are accepted at ‘face value,’ the effect is that the land where the bothersome town road had existed for more than 100 years would retroactively become owned by Novogratz.

“Brandishing the new ‘Confirmation’ and ‘Correction’ deeds they filed, Novogratz’s lawyers asked the County tax map agency to ‘correct’ the tax map to show no road was actually there. The County honored this request.”

Thus, back in March, the County simply erased this portion of Cross Highway on the East Hampton tax map and prepared a new map that no longer shows an unpaved portion of town highway bordering Novogratz’s five-acre parcel. Instead, the new tax map shows that the five-acre parcel had been expanded to swallow up the land where the “non-existent” town road had been.

“What did you do?” I asked Buda.

“I went down to the appropriate office in the County center, and showed how the 1921 deed that was relied upon to erase the roadway and grab the highway land could not lawfully supersede the correct property description in the County-issued 1938 Tax Sale Deed and all subsequent deeds in his chain of title,” he said. “I also presented all the original 1914 East Hampton Highway Department records which detail the laying out and acceptance of that road as a Town highway. That could only have been done pursuant to Town Highway Law, with the permission of, and all land claims having been released by the owners of the property.

“The Town Highway that was laid out in 1914 went from Cranberry Hole Road past the Novogratz parcel, across Abraham’s Landing Road and onto Fresh Pond Road. And at every turn the Town’s surveyor had placed a marble monument to ‘witness’ the existence of the Town Highway. Novogratz’s own surveyor had located all those marble monuments, but the new deeds, in essence, say ‘forget about it.’

“And after taking a couple of weeks to study all available deed and Town Highway records, the County officials ordered the removed Town road be put back on the map.”

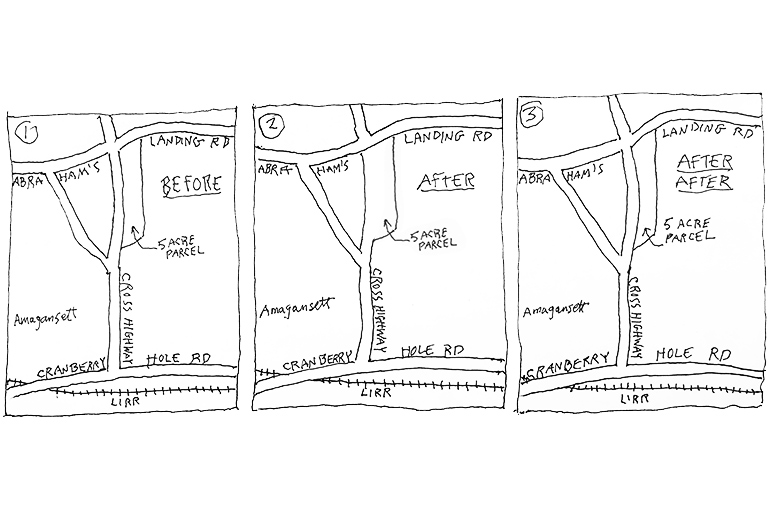

Buda has before and after maps. And he also has the after-the-after map showing things as they had been before.

“It’s all fixed now,” Buda told me.

I put several calls in to our East Hampton Town Supervisor, Peter Van Scoyoc, so I could talk to him about this matter. But so far he has not returned my calls.

I did speak to Stephen Latham, Novogratz’s lawyer, and asked him if they are eventually able to delete the road, would it mean the end of the trail there? The trail then would cross this

private property.

“Nothing in my client’s proposal would interfere with the trail in its present location,” he said.

And now it turns out that though Buda said it was “all fixed,” it wasn’t.

On November 7, which was in the interval when Novogratz had a county tax map more to his liking, he filed for, and got, a building permit from the town based on that map.

When Town officials learned of this, they were horrified. Almost immediately, Anne Glennon from the building Department issued a stop work order.

“We know who the contractor is. We contacted him immediately,” Glennon told me. “He hadn’t yet begun moving the house.”

She wants to see an “up to date” property survey based on the current county tax map, which obviously would not be the same as the one he had shown to get the building permit, she told me.

Then it was found that NO TRESPASSING signs had been tacked on the road. Violators would be punished to the fullest extent of the law.

The Town sent Andrew Drake, an official from its Land Acquisition and Management office, out to remove them. He found some of them tacked directly over posted wooden signs that declare the land part of the Paumanok Trail.

“Not sure they did that deliberately or not,” he wrote in an email.

And there the matter stands.

It seemed to me this was getting way out of hand, and it gave me an idea. The whole point of this from Novogratz’s perspective, Mr. Latham has said, was to have room to move the Fleetwood house to the smaller property without the need for variances. Somewhere they needed another acre to make this happen.

Thirty-two years ago, I bought two adjacent properties. A house was on one, nothing was on the other. But it was awkward. I could make it right if I could adjust the property line between them. I applied and the town went along with it.

I called Mr. Latham and told him about it. It seemed to me that if he deeded one acre from the 33 acres to the 5 acres—the very same sort of property adjustment I did—it would solve the problem.

“It’s one of the many things we need to consider,” he told me.

A lawyer’s reply. Well, he heard me.