Thiele: Hit Pause On New Criminal Procedure Laws

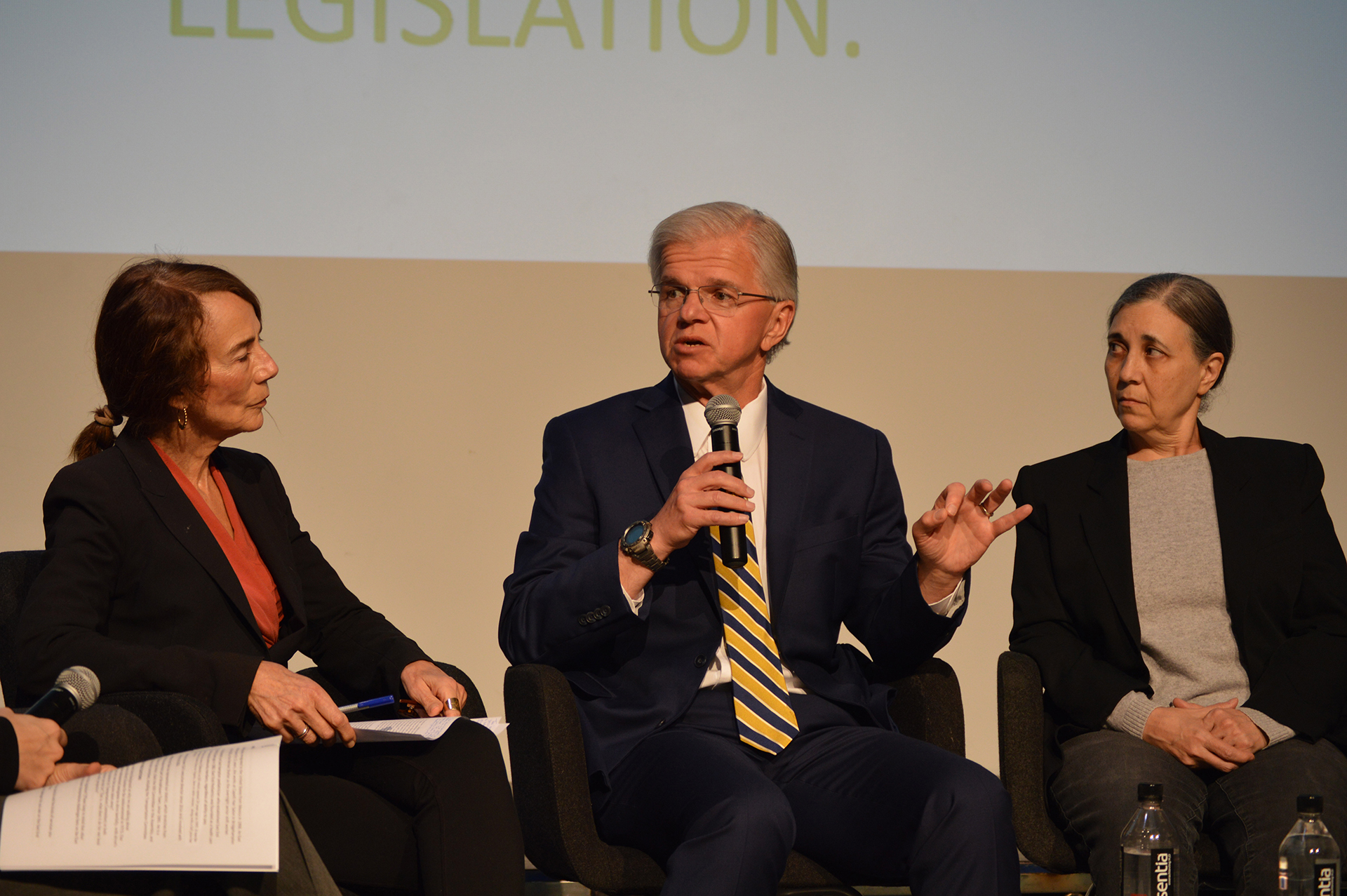

Assemblyman Fred Thiele is accusing Governor Andrew Cuomo and New York City legislators of using stealth methods to pass radical criminal procedure law reform last April that Albany County District Attorney P. David Soares estimated could cost taxpayers over $1 billion to implement. Departments across the state are already required to adhere to the changes the law requires.

Suffolk County District Attorney Tim Sini had to create a new bureau of assistant district attorneys on the job 24 hours a day tasked with meeting a new law requiring that all information gathered by police must be shared with the defendant within 15 days. There was no such clause in the old law.

The reforms were contained inside the $175.5 billion state budget for 2020.

“It was shoe-horned into the budget,” Thiele said. “The budget should be about the budget. The governor is fond of trying to include as much policy as he can,” in the state’s financial plan.

According to Thiele, if the reforms had been presented to the Legislature as stand-alone bills, they would not have passed.

The new budget goes into effect January 1, along with the new criminal procedure law reforms. The budget contains no funding for the law’s implementation.

Thiele said lawmakers are loath to vote against a budget when it contains money vital to their local communities, for example, money for schools, or medical care, or, specifically in the case of Thiele’s first district, programs like the South Fork Commuter Connection.

“That is why they stuck it in,” he said.

Thiele would like to at least delay implementation until April, when funding for the changes could actually be allocated as part of the following year’s budget process. He is working toward that end with 10th District Assemblyman Steve Stern, whose constituents reside in Huntington. The hoped-for delay in implementation does not appear likely though, he admitted.

The reforms were spurred by the crumbling criminal justice system in the city, particularly in the Bronx.

Thiele was reminded of the case of Kalief Browder, the 16-year-old accused of stealing a backpack in the Bronx in 2010. Unable to post the $2000 bail that was set for him, he remained in jail for 997 days before being released without ever being trialed. He eventually

committed suicide.

“Nobody can defend that case,” Thiele said. “But hard cases make bad law. They went too far.”

The new laws governing bail have received the most attention in the broad sweep of reforms just days away. Drug dealers selling fentanyl-laced heroin, for example, will now receive appearance tickets from the police instead of being held, unless they are charged as major drug traffickers; a difficult legal threshold to reach. Thiele said the new laws take away “a judge’s ability to consider whether or not the defendant presents a danger to the community.” “Once we see the consequences of some of the provisions,” he added, “this law it will get a lot of attention.”

This is part two of the three-part series. Next week: The costs of criminal law reform.

t.e@indyeastend.com