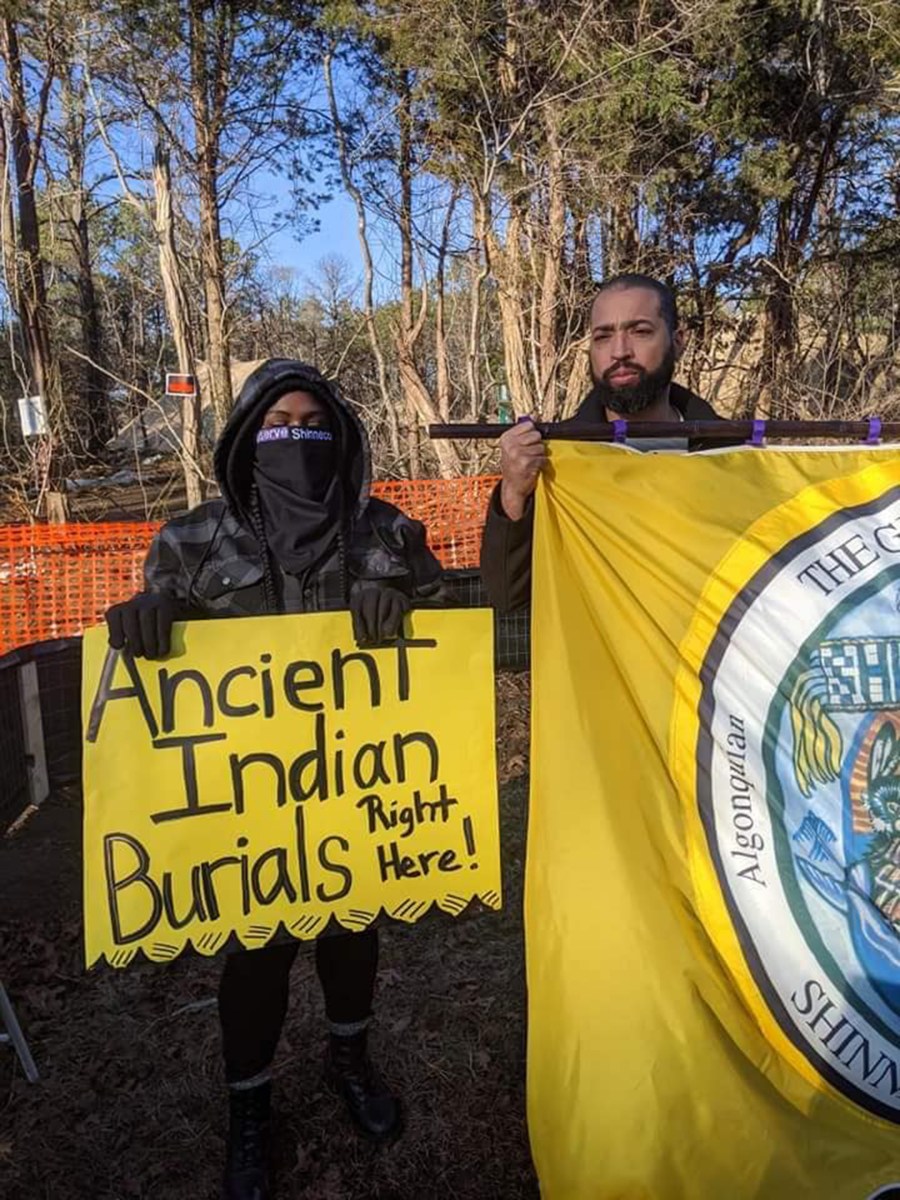

Shinnecock Protest Building On Ancient Burial Grounds

The Shinnecock Indian Nation is waging ongoing protest to protect its ancient and sacred burial grounds on Shinnecock Hills.

“If you went to a Colonial gravesite, you can’t dig something up without there being consequences. So why are there no consequences when someone does that to our gravesites? Or build on it?” Shinnecock Indian Nation Council of Trustees Vice Chairman Lance Gumbs said. “It’s a joke.”

Since December, tribal members have staged rallies at a worksite on Montauk Highway calling on the town to issue a cease-and-desist order for construction said to be taking place at a property adjacent to the Nation’s Sugar Loaf Hill burial grounds. Another demonstration took place January 14. Tribal leaders said they were shocked to find out about the construction via a drive-by. Although under different circumstances, the Shinnecock Indian Nation entered a verbal agreement with Southampton Town following construction on nearby Hawthorne Road in 2018 after remains were found during excavation, to ensure the tribe’s sacred land would be protected.

“We had this verbal agreement. We had this understanding that the nation would be notified if any digging were to transpire. And poof,” Gumbs said. “This is the Catch-22 we’re running into. It’s been frustrating. There was supposed to be discussion. There’s a clear sense the town feels it just doesn’t have to do it.”

The property is in a state Department of Environmental Conservation-designated Critical Environmental Area, but the town authorized a subdivision of the lot last year and in November issued a building permit for a two-story home. Tracker Archeology, Inc. executed a Phase I archaeological survey of the site — to determine if there is a presence of archaeological resources within a project area — and found no prehistoric artifacts, according to a planning board resolution. The level of effort necessary to reliably document this is largely dependent on the extent of ground surface visibility, and in this case a few test pits were shoveled out, extending into the natural subsoil.

“They didn’t find anything, and the Shinnecock are suspect of the result,” Southampton Town Supervisor Jay Schneiderman said. “To have a member of the nation there would go a long way, but at this point it’s not the law.”

That’s why he said members of the town will be meeting with tribal leaders this week to create legislation the supervisor said would address a series of steps to be taken when human remains are encountered. Schneiderman said the town has been in talks with the property owner to preserve the parcel, but that it “may not work in this case.”

“We’re aggressively buying what we can, but that doesn’t mean we’ll be able to buy everything,” he said, adding while the owner has a buyer and he doesn’t “think we’ll be able to do anything about that lot,” the town is in conversation with the gentleman over two other lots the town is appraising. One is behind the current construction site.

Southampton also has a 3D imaging system — ground-penetrating radar — a geophysical method that uses radar pulses to image the subsurface that can detect remains without disturbing the area. The supervisor said the town currently needs property owner consent to bring the equipment to the worksite.

“We don’t want people to fail to report these incidents, and that’s the fear,” Schneiderman said. “Some people look the other way and that’s the worst thing that could happen. We certainly want to make sure no development occurs in an area where there may be human remains.”

Gumbs said because the site has been labeled sensitive it should have required at least a Phase II archeological survey, where additional background research is done and designed to formulate specific questions to be addressed during fieldwork. Instead of a set of guidelines for when remains are found, he’d like to see regulations similar to the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act. The law, although not pertaining to private property, protects the land while establishing ownership of cultural items excavated or discovered on federal or tribal land. The council’s vice chairman and other tribal leaders, though, are fearful conversation will once again stall. After the town purchased the Hawthorne property last year a committee was created that included three Shinnecock members. Gumbs said the group met twice since the purchase, and said these individuals, who were working with those managing the town’s Community Preservation Fund department, were not notified of the construction either.

Photos from previous protests have been displayed on the tribe’s 61-foot-tall billboard-like signs, known to the tribe as monuments, and the issue was also highlighted in the recently-released documentary “Conscience Point,” which followed tribal member Rebecca Genia’s years-long battle with the town over protecting Shinnecock gravesites.

“You have a lot of powerful people with a lot of money in this town who want things done and get it done. It’s this whole rubber-stamping process,” Gumbs said. “They’re disturbing our ancestors and that goes right to the core of who we are as Indian people and it is disturbing and heartbreaking to us to watch the continued desecration of these areas. The town knows them and we’ve identified them; they’re on a sensitive site map. We’re going to continue the fight no matter what. We’re going to continue to be out there protesting anyone that wants to try to continue to do this.”

desiree@indyeastend.com