Story a Day: Writing a Story Every Day for Years

I had dinner with Si Perchik, the poet, the other day. Si lives at Maidstone Park in East Hampton, and for as long as I can remember, has been writing poems every day. He doesn’t drive, so he takes the county bus to the East Hampton Y, writes there for a few hours, then walks to the Golden Pear and writes there for a few hours, and then walks to the library to write some more. He walks about two miles doing this. Then he’s home again by bus.

He is surely the most prolific poet alive in America. His work, which has been described as highly personal and non-narrative, has been published in The New Yorker, The Nation, Partisan Review, Poetry, The North American Review and so many other places. He’s authored more than 20 poetry books.

His early career was as a lawyer with poetry on the side here in Sag Harbor. He retired at 57 in 1980, decided he could do without a car, and has been writing since. He’s now 96.

“I don’t know,” he said when I asked him how he puts words one after the other. “I just look at where I am in the poem, then there’s a word that just fits, so I put it in. When it’s done, I come home.”

Si now lives alone. His wife and son have both passed. But he’s not lonely. He meets people during the day. And he likes poetry.

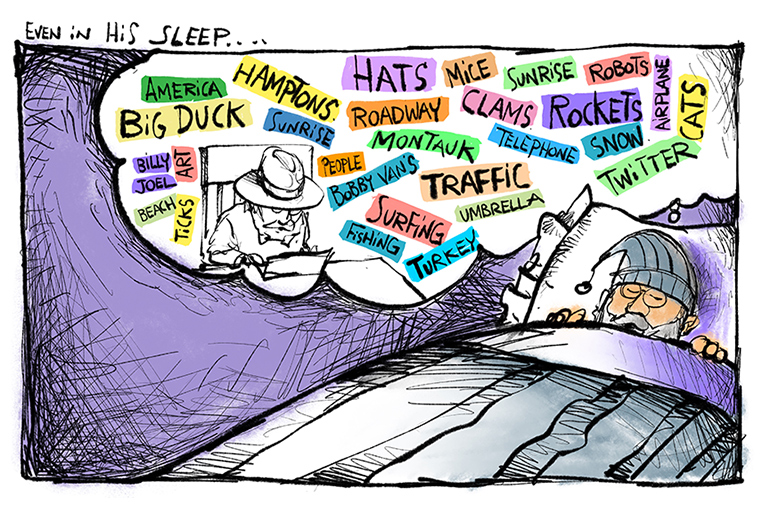

I’ve been writing a story a day for Dan’s Papers for even longer than Si has been writing poems. And I, too, have been a vagabond, always looking to write in different places. I write at the beach in Sagaponack, at the Bridgehampton Starbucks, at the Southampton Library, and in the living room of my home on Three Mile Harbor Road. I write about whatever comes along. Humor. Local affairs. Crazy stories. History. And I’ve also written books, though not as many as Si.

After I started writing my stories for Dan’s Papers all those years ago, my great aunt Bertha Klausner commented that I was apparently embarking on the same quest her father went on. His name was Jacob Adler, and for nearly 80 years, 1897 to 1975, he wrote a daily column under the pen name B. Kovner for the Jewish Daily Forward in New York City, only stopping when he died at the age of 102. He wrote humor, crazy stories, local news, history or whatever crossed his path. Reportedly he wrote 18,000 poems and 30,000 stories.

I am nowhere near that number. By my own estimates, I’ve only written about 15,000 stories.

Here’s a story Adler wrote. It’s in a hardcover book of his collected works.

“A rabbi teaching at a nearby college chastised his students one day for going to a soccer match rather than studying for class. ‘Rabbi, come with us and you’ll see what we love about soccer,’ one of his students said. So he went.

“When the first half ended, he told his students he had solved the problem. What problem?

“‘Give a second ball to the other team. If they both have balls, there’d be no more fighting over just the one,’” the rabbi said.

Bertha Klausner’s husband, Ed, who was a successful millionaire inventor and a builder of tall buildings in Manhattan in the early part of the 20th century, told me many stories.

At family gatherings, Ed would gather all us kids around and tell us stories about the time he fought the Germans in World War I.

“My job was to guard the reservoir in Parsippany, New Jersey. I stood on the reservoir’s shore and kept watch. One night I saw the Germans sneaking slowly around the reservoir in single file, but on the other side. I only had one bullet. So I put it in my gun, bent the barrel so it would fire the bullet in a big circle, and BANG, it went around the reservoir, through the whole line of Germans, then all the way around back into the rifle so I could use it again.”

Ed had invented something called an S clip, a small S-shaped piece of iron that held wooden floors suspended between I-beams while you poured concrete floors on top. When the concrete dried, the S clip would be broken with a hammer and the wood floors would fall away. It made it unnecessary to build temporary post-and-beam structures to hold up wood floors while concrete was poured on top.

“Whenever a builder anywhere uses an S clip,” my mother told me, “Uncle Ed gets a penny.”

Once when I was about 10, Ed invited me to join him in the back seat of his limousine while his chauffeur drove us to a real estate closing in Garden City. He owned much real estate in that town. On the way, here is what he said:

“If the deal is being done in the kitchen,” he said, “don’t you be in the living room.”

In his later years, Ed designed and supervised the building of my dad’s store, White’s Department Store on the circle in Montauk. Ed had suffered a stroke but supervised the construction by calling my mother every day from his wheelchair in Manhattan. “Did the trusses come?” he’d ask. “Look out the window.” Mom was in the old White’s Pharmacy around the corner.

But here’s the most astonishing story. Ed and Bertha lived in separate apartments across the hall from each other on the 12th floor of a 1920s era apartment house on the corner of Lexington Avenue and 41st Street. I remember visiting them there. Ed was “entertaining women friends,” my mother told me. Bertha, meanwhile, was running a literary agency out of her apartment. They’d been there a long time. But one day, the building got sold and the new owners were evicting tenants because they were going to make it into an office building.

One afternoon, Ed came home from his office, took the elevator up to the 12th floor and saw construction workers in the hall wielding sledgehammers. At this point, Ed and Bertha, holdouts, were the only tenants left in the building.

Ed stopped where the men were hammering through the wall to expose the steel I-beam inside. Ed took out a measuring tape, measured the steel, thanked the men and then went to Bertha’s apartment. “We’re staying,” he announced.

He then called the owners of the building and told them that the steel beams holding up this building were strong enough for residential use, but not strong enough for office use.

The next day, the owners of the building were in the apartment with Ed and Bertha to tell them they had found a huge 10-room duplex apartment on Park Avenue at 38th Street and would pay for them to live there for the rest of their lives. They accepted the offer.

Years later, I interviewed a prominent New York City builder who owned this building at that time and confirmed this story.

“We had no idea your Aunt Bertha would live so long,” he told me. She was 58 when the offer was signed. Ed passed on but Bertha ran her International Literary Agency until she was 97. She passed on at 99. That was in 2004. (Her agency continued on for years after.)

Recently, I stumbled upon an essay published in Tablet magazine in 2008, written by Rebecca Spence. She wrote about her growing up amongst her famous relatives, one of whom was Jacob Adler. Here is what she wrote about Adler’s daughter Bertha.

“My great grandmother—Adler’s daughter Bertha Klausner—was a crackerjack literary agent and the fiercely independent and forward-thinking family matriarch. Bertha entertained the leading writers, producers and performers of her day from her capacious apartment on 38th Street and Park Avenue. She served up lunches of whitefish and brisket and inked book deals for her bevy of celebrated clients, among them Marcel Marceau and Upton Sinclair.

“As a child, I instinctively gravitated toward this beatific woman with her huge bosoms and crown of silver hair. She fed me Entenmann’s chocolate cake, smothered me in mama-bear hugs and was known for her constant refrain at family gatherings: ‘All my great-grandchildren are geniuses.’”

I think she had 10.