Thomas Moran: Eccentric 19th Century Artist and His East Hampton Home

For nearly 150 years, the Hamptons has been home to many great artists. And yet I know of only three that have, since their passing, had their homes restored and kept up in the manner they were in when the artist and his or her family lived in them. All three are in East Hampton, about three miles from one another. They are accessible to those interested in visiting them by appointment. A guide will take you through them.

One is the home of Jackson Pollock and Lee Krasner in Springs. Pollock, in his prime, worked at this home between 1946 and 1956, when he died in a car crash at the age of 44. He was considered in those brief years as perhaps the greatest painter in the world, the most celebrated of the group of new Abstract-Expressionist painters whose movement revolutionized the art world during that generation. Much has been written about him and Krasner, his wife and also a notable painter from that period. Jackson laid his canvases across the ground outside or inside in an adjacent studio so he could drip paint on them. He was brilliant, volatile, often drunk, a lover of many women and the subject of the 2000 film Pollock, in which he was played by actor Ed Harris.

The second is the studio of Victor and Mabel D’Amico by the Art Barge in Napeague.

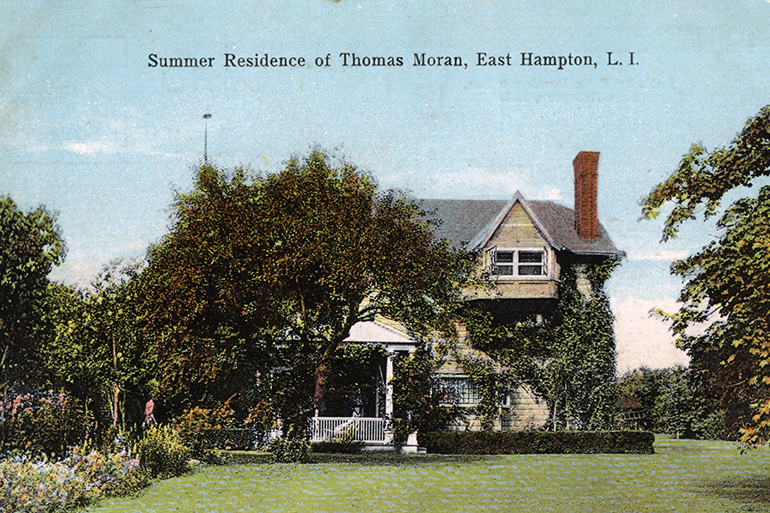

The third artist’s home here, a labor of love, just opened this past summer after six years of careful reconstruction and renovation. Unlike Pollock’s house, which was a small 60-year-old cedar-shingle affair with a front porch that the pair rented, this restored artist’s home was a grand English mansion in the Queen Anne manner, with turrets and picture windows facing out onto Town Pond in the center of town. It was built in 1884 to the specifications set down by the painter himself, Thomas Moran, a man then in his 40s and already filled with honors as one of this country’s great landscape painters.

Thirteen years earlier, Moran had gone on a series of government survey expeditions to the Grand Canyon, Yellowstone, the Colorado River and Yosemite to draw what he saw. He went with a photographer, F.V. Hayden, who was charged to take pictures. The expedition was on horseback, with mules carrying tents, gear and the equipment of Moran and Hayden, and in photos taken by Hayden you often see Moran, young and vigorous and covered with dirt, sitting on a boulder by a cliff and sketching the wonders he saw. Returning home, the sketches turned into oil paintings.

His work so inspired Teddy Roosevelt, among others, that when he became president, Roosevelt went off to see the locales for himself. Today, Moran’s paintings are in the White House, the Smithsonian and other national galleries and museums. But some are also at the Thomas & Mary Nimmo Moran House itself, here in East Hampton.

Moran was born in Bolton, England in 1837, but at age 7 was brought to America to Crescentville, a neighborhood in Philadelphia, by his parents. He became interested in painting at an early age, and in his 20s was already developing a reputation in that field. He had a studio he shared with other painters, and in 1862, after visiting and drawing in the Wisconsin wilds by Lake Superior with his brother, fell in love with a fellow painter who, two years younger, was also from Crescentville. Her name was Mary Nimmo. And she had been brought to Pennsylvania by her parents from Scotland in the same period that Moran’s parents brought him from England. They became a handsome young couple, married in 1864—this was during the Civil War—and took up residence in Philadelphia, where they had three children, a son and two daughters. It was just eight years later that Moran went on his first expedition to the Wild West and made the oil paintings that made him famous.

After a brief time living in the small industrial city of Newark, New Jersey, Moran and his family moved to Manhattan and soon after discovered the beautiful landscapes of eastern Long Island. The year was 1878, and it was only a few years earlier that train tracks had been extended out east. Prior to that time, it took 10 hours by boat or three days by stage coach or horseback to get here. This was a rural oceanfront landscape of farms, colonial towns and fishing villages, and now it was just a three-hour train ride from Manhattan. They took the train to Bridgehampton, where the tracks ended. It was by stagecoach after that. A small summer colony had been established by the wealthy out here by then. Five years later, in 1882, Moran bought a parcel of land facing out onto Town Pond with the two-lane Main Street cutting between, where his three-story home stood.

His kids were teenagers. Out here, Mary Nimmo created beautiful etchings. She eventually made more than 40 of them. Her work was later shown in the Women’s Building at the Chicago World’s Fair in 1893.

The ground floor of the mansion is almost entirely made up of the artist’s studio. It rises to 20 feet and has tall picture windows that let the light in from the south and east. Halfway up in this high room is an inside balcony used as a living room. Guests could look down into the studio. Or go out into the turret adjacent. Then up on the third floor were four bedrooms and a bath. You can take a tour through all these rooms today. All have been restored in the Victorian style, with mahogany wood paneling and other dark surfaces. And even from upstairs, you can look out more large windows to the front lawn, where, for many years, Moran kept a 50-foot gondola he had bought when he and his family visited Venice in 1891. It came back to America with them, strapped to the deck of a steamer. In the summertime, the gondola would be carried to a dock in nearby Hook Pond to be floated out as the centerpiece for picnics and parties for families and friends.

In August of 1898, having won the Spanish-American War, 32,000 soldiers of the U.S. Army returned to America from Cuba aboard troop ships and set up thousands of white tents on the rolling hills of uninhabited Montauk, 16 miles away. Many of these soldiers, including Teddy Roosevelt and his Rough Riders, were here for a month to recover from highly contagious tropical fevers before being allowed to be decommissioned and sent home to their families.

Hospital tents were built. Doctors and nurses were brought to Montauk to attend to the sick in them. And locals were among those out there to help, including Moran’s daughter Ruth, about 20 at this time. Unfortunately, she came down with typhoid fever. Her mother went out to Montauk to be with her, and eventually she recovered and came home. But Mary Nimmo, age 56, then came down with the disease and died. She was widely mourned and was buried in the South End Cemetery across the way.

Thomas Moran, bolstered by his friends, lived on in East Hampton. There are photographs of him, a white-bearded older man at his easels. It was the fashion back then for men to sport beards. Abe Lincoln had one, Mark Twain had one and so did Thomas Moran.

He lived out here into his late 80s and traveled widely. He was much loved. When he died, in 1926, his house became the home of Boots Lamb and her family, and Boots ran a real estate office out of this home into the 1970s. After that, it became vacant and overgrown. Ten years ago, it was seen that the weight of the upper floors and the turrets were causing one of the side walls below to bulge. It would have to be torn down.

Or it could be, with great expense and effort, saved.

And so, the project was taken on by a group called the Thomas Moran Trust. For several years, timbers pushing in from the outside acted as buttresses to keep the house steady. And then, well, here it is.

The Executive Director of the East Hampton Historical Society, Richard Barons, gave me and my wife the tour. We loved it. You will too if you get the chance. Call 631-324-6850.