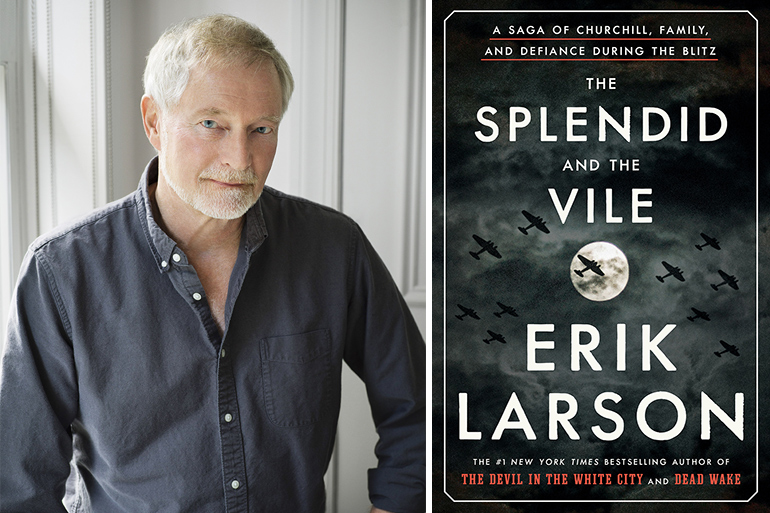

The Splendid and the Vile: Erik Larson Views Churchill Through Fresh Lens

Southampton resident and bestselling author of The Devil in the White City and Dead Wake Erik Larson is the first to admit that he’s dipping into a crowded pool with his latest subject, Winston Churchill. But Larson’s new book, The Splendid and the Vile (out on February 25), examines the beloved British statesman through a fresh lens, sharpening its focus on the man’s remarkable first year as England’s prime minister from May of 1940 to 1941, and the early days of World War II.

This fraught period was defined by months of brutal bombings, killing some 45,000 Brits—30,000 of them in London alone—during Germany’s Blitz, but it was also a time of great heroism and resolve as Churchill led his country through the fear, and never capitulated to Hitler’s aggression. Larson captures it all in his meticulously researched and riveting narrative style, while offering new insights into Churchill and, specifically, his close cadre of advisers and family members who were vital to his success.

As Larson tells it, his inspiration for The Splendid and the Vile didn’t come during a trip to London or the battlefields of WWII, but rather when he and his wife, neonatologist Dr. Christine Gleason, began the process of moving to Manhattan from Seattle in 2014. “I had kind of an epiphany about 9-11,” the author says, describing how his thoughts arrived on London and the Blitz. “In Seattle we watched [9-11] unfold on CNN in real time, and as horrific as it was, when I got to New York, I realized the experience of New Yorkers was an order of magnitude worse. Not only was everything live and in your face, from smoke to ambulances, to fire trucks screaming down Fifth Avenue, but it was also that sense of violation. This was your home city that was attacked,” he explains. “I got to thinking, what must have it been like in London to have essentially 57 consecutive 9-11s during the German air campaign against Britain?”

Larson asked, “How do you go about surviving that?” before eventually looking to Churchill, “the quintessential Londoner” at that time. “How did he do it? Not only did he have to endure this bombing, but he also had to direct the British side of a world war.” From there, Larson’s vision quickly took shape.

“Once you have a reasonably fresh window on something that many other people have written about before, you see it in a new way,” he says, noting that this new window colors the hunt for historical documents and material, which will inevitably reveal morsels other scholars and historians may have overlooked. This was indeed the case when Larson dug into the National Archives of the UK, the United States Library of Congress and similar repositories of historic papers. Meanwhile, he avoided going too deep into other books about his subject—and there are many. “I knew there had been tons of stuff written about Churchill, obviously, but I guess I didn’t really appreciate the sheer amount of it,” Larson muses. “You could not read everything, even if you devoted a decade to doing so. And honestly, if you devoted the decade you still wouldn’t be able to do it, because 10 years out there’d be another 20 books.”

Perhaps most importantly, Larson gained privileged access to a diary written by Churchill’s daughter Mary, who was just 17 years old at the start of his book. “I was given the very rare right to look at and use [Mary’s] diary by her daughter Emma Soames,” he says, noting that Soames became a fan after reading his “respectful portrait of Churchill” in Dead Wake, Larson’s 2015 book about the ill-fated Lusitania. “According to the head of the Churchill Archives Center, I am one of two scholars who have actually seen this diary—honestly, I think that’s what makes the book,” he adds. “She was a very detailed and accurate observer, and she kept this diary religiously every single day, but she was also a very articulate writer full of insights into the times.” Of course she also offered a true insider’s view of her vaunted father.

Through Mary’s writings, recently declassified files, intelligence reports and the unearthed words of Churchill’s wife, children and “secret circle” of advisers—including his private secretary John Colville, newspaper baron Lord Beaverbrook and science adviser Frederick Lindemann—The Splendid and the Vile delivers a unique perspective on the prime minister’s profusely chronicled life.

Churchill’s controversial order, for example, to bomb the French fleet at Mers el-Kebir on July 3, 1940 to stop it from falling into German hands, is shown to have been painfully difficult for him. His actions resulted in the death of 1,300 French sailors, who were allies of Britain, but the move also proved Churchill would do whatever it took to triumph over his enemies.

“I don’t think its true meaning and the character of it have really been given their due weight,” Larson says, noting this attack was the moment America, and probably Germany, knew England would fight for the duration. But he might not have done it without support, and the book offers a detailed narrative of Churchill’s struggle to arrive at his final conclusion. “It says a lot about how much Churchill needed his advisers, how close he and Beaverbrook were, and also how passionately Churchill felt the more tragic aspects of war. War thrilled him, there is no question, but he was not a sociopath.”

The Splendid and the Vile is an engaging read and a valuable addition to the Churchill canon, as well as the historical record of Britain’s early role in World War II. And, thanks to Larson’s efforts, the book paints indelible new strokes on history’s picture of the great man.

“What was compelling about Churchill was that from the start he had this incredible confidence that Britain in the long run would be victorious. How he had such confidence, how he got that, I don’t know,” Larson says. “I think it cuts to something very fundamental, and that would be character. Wherever that comes from, your guess is as good as mine. But he had that depth of character that let him be confident from the start that Britain would prevail.”

Erik Larson’s The Splendid and the Vile (Brown Publishing) arrives at bookstores everywhere on Tuesday, February 25. It’s also available now for preorder from online retailers.