Walking Dunes: The Daring Attempt to Climb All the Way to the Top

Who can forget Tensing Narsik and his climb up to the top of the Walking Dunes in Napeague? The year was 1911, and that July he came out to the Hamptons from his native Finland to attempt what was, until that time, the impossible.

I presume you are familiar with the Walking Dunes. Today you can read about them on all East End tourist attraction websites. The wind blows north to south and the sand atop the dunes is pushed up one side and down the other, thus moving the peak as much as five feet a year in a southerly direction. The next year, it might blow from south to north so the sand all gets blown back. You can, if you want, trudge the 400 feet up to the top and enjoy the view.

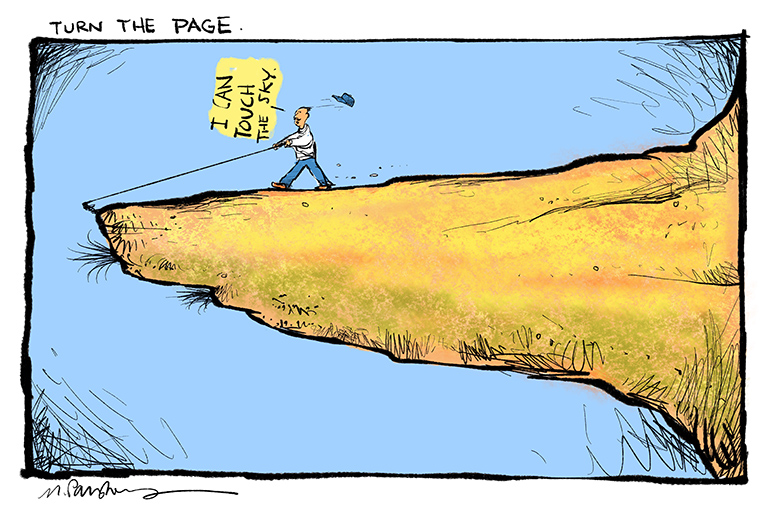

But that’s not what the Walking Dunes were like in 1911. They were so high back then that the peak was shrouded in clouds 12 months a year. No one had ever climbed to the top. And so therefore nobody knew how high the peak was. Perhaps it was even higher than Mount Everest.

And then, in 1911, there came to New York the celebrated Finnish climber Tensing Narsik.

Narsik, who was 26 and in peak physical condition, arrived aboard the ocean liner Olympic—the sister ship to the Titanic that would hit an iceberg and sink the following year—and he spent a week in Manhattan, gathering up gear, buying supplies and giving interviews to the reporters of all the daily newspapers in that city—the New York Herald, the Times, the Journal and the Post and more than a dozen others.

One memorable interview he gave was on the sidewalk in front of Abercrombie & Fitch, the noted athletic supply clothing store in Manhattan. He stood ramrod straight to his full six-foot-five height. His long blond hair blew in the wind.

“It will take days,” he said. “Maybe weeks or even months. But I am ready. There is no mountain on earth, even a sand mountain, which I cannot climb.”

Although Narvik spoke very loud and thus was easy to hear, he also spoke very fast and only in Finnish, so much of what he said never got translated or scribbled down onto reporter pads. But the paragraph above is, in retrospect, approximately all of what he said as best as can be determined.

Of course, at all these interviews, Narsik wore around his neck the five gold medals he had won for his climbs at the Olympic Games in prior years. Climbing was an Olympic sport back then in 1911.

Telephones, a new invention, had been installed in most big cities in America by this time, but none had yet made it to eastern Long Island. A few years earlier, though, a man named Marconi built this enormous 300-foot-tall steel tower in Napeague, still there today, from which messages could be transmitted around the world and out to ships at sea by operators tapping out dots and dashes on an electrical key from inside the small building adjacent to the tower. Indeed, the Olympic, bringing Narvik to New York on its maiden voyage, had sailed to New York Harbor guided by Morse code messages.

Anyway, Narsik said at another of these interviews that beginning on the second night of his ascent and every night thereafter, he would communicate via Marconi’s new Morse code with the outside world. One of his three “Bonackers,” as he referred to the East Hampton locals he had hired, would be lugging the first-ever portable Morse code machine along the ascent. It weighed 55 pounds and cranking it 50 turns would give him 20 seconds of tapping. He would tap long or short signals for those brief moments at 9 p.m., local time. His updates would be read to the reporters out front of the Marconi building. So they’d get their stories.

Marconi himself stood alongside Narsik when Narsik made this announcement. Marconi was much smaller than Narsik, but nevertheless he smiled and bowed when introduced.

Norsik and his Bonackers began the climb on the rainy morning of Monday, July 9, 1911. At exactly 9 p.m., he tapped out his first report.

“Still raining. Spirits are high. We’ve made camp at 12,423 feet. Blisters. Rain coming down in briskets.”

The reporters decided he meant “buckets.”

On the second and third nights, more messages came through, including a report of swarms of wasps at their camp. He indicated his altitudes as 15,833 and 19,411, respectively. But then, after that, for three straight evenings there were no further messages. The reporters were concerned on the first night of silence, then alarmed at the second and third.

The next afternoon at 4 p.m., the reporters were informed that a message was coming in. They came running over to the Marconi building.

“Many white wolves,” was the tap. And that was it. The reporters were in a frenzy. What had he meant? Maybe he meant “wools?” It was known he had headed up wearing three sweaters made of special kinds of wools. And how high was he?

The next night, at the regular time, Narsik tapped out “Binnickers Coming Down. Slashing sleet storm. Snow sideways. And crickets.” And again, there was no indication of the altitude.

Indeed, the next day the three Bonackers, empty handed, arrived down at the Napeague Harbor Road base camp, huffing and puffing— it is so much faster coming down than going up—to report that indeed they had encountered white wolves the previous two days. But the wolves were friendly and had jumped up into their arms and licked their faces, which, one of them said, “we did not appreciate.”

“But we were almost at the top,” the second Bonacker said. “Through the blinding white snow storm and the packs of crickets, we got glimpses of it. It’s a magnificent jagged peak beneath an azure blue sky.” The Bonacker was being poetic. “Narsik went on up this morning, singing a folk song in Finnish, and I am sure he made it, but we were done, bub.”

Bonackers usually said “bub” at the end of a sentence back then.

“So we had to come down. Bub.”

The Bonackers also said they were reading 35,466 feet, which would make it taller than Everest, but then the glass on the front of the brass altimeter cracked and the needle inside froze.

“So we left it there,” the second one said.

That was the last anybody heard of Tensing Narsik. Or saw him.

Six days later, his wife, who is from Norway, arrived, but it did no good.

Although in subsequent years the strong winds kept scooting sand along and lowering the peak of the Walking Dunes, it wasn’t until the Hurricane of 1938 that, in just one blow, it got flattened to the modest height of the 500 feet it is today.

Although it has been climbed many times since, often by the same person over and over, it is still truly believed that Tensing Narsik, on or about July 13, 1911, climbed higher above sea level than anyone ever did before or since. After all, there is no place on Earth higher than the top of Mount Everest, or, for that brief geological time for however long it was, the top of the Walking Dunes in Napeague.

In 2017, a vicious windstorm slashed along the shoulder of the Walking Dune, and amidst swarms of wasps and crickets, an old leather climbing shoe was “coughed up” from just beneath the current peak, but it doesn’t appear to have been Narsik’s size.

But nobody knows for sure.