Official Seals: Good and Bad in East Hampton and Southampton Villages

The Village of East Hampton has come out with a new Village Seal. The old one, and I’ll get to that, has been around since 1654, so maybe it was a time for a change.

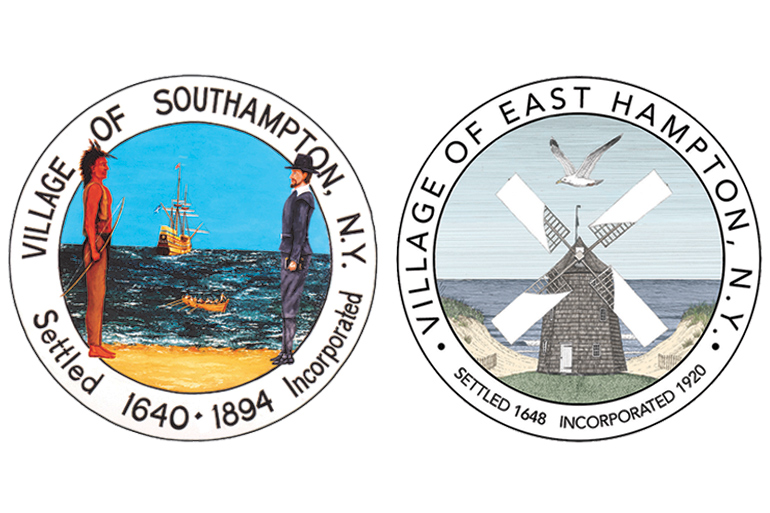

Village or town seals are on the walls in courtrooms, at the top of official proclamations, on signs at village entrances and sometimes on the sides of police cars. Usually they are round. Why, I do not know. In this case, the new seal is round, as is the old. But boy, are they different within the circle.

The main feature of the new seal is a big wooden windmill with white canvas covering each of its four blades. Above it hovers a seagull. In front of it is a piece of the Town Green. Behind it is a sand dune, and at the back, the blue ocean. It’s a peaceful day.

The old Village Seal had a round circle with a shield inside similar to the one that graces the village of Maidstone in the province of Kent, England. That shield, often at the end of a spear on a battle flag back then, was based on the family coat of arms of William Courtenay, the Archbishop of Canterbury (d. 1396), who is said to have been the founder of Maidstone in 1619. It consists of three torteaux gules denoting the River Midway, which flows through Maidstone, and at the top the shield’s chief bears a golden lion passant on a white field of gules, signifying that the Village was founded by a royal charter.

It seems the Village of East Hampton was founded in 1648 by settlers from Kent, and they, wanting to do honor to their home town settled 29 years earlier—and so, here is the really interesting part—didn’t call this new place East Hampton, they called it Maidstone. It wasn’t until about 1685 that the locals here decided to change the name of the village to East Hampton. People were apparently calling it that anyway, because the first settlement was Southampton, the second settlement was Bridgehampton, and then a little further along was East Hampton, er, Maidstone.

Hallelujah. It’s about time the Village changed this botch job of a seal.

The Village of East Hampton is not the first local municipality to adopt a seal change in recent years. About 20 years ago, residents of Southampton Village got all in an uproar about their village seal.

That seal, which went back a hundred years or more, showed a Shinnecock Indian with a feather in his hair and wearing just a loincloth, standing and facing a fully suited English pilgrim. It’s a side view of this meeting. In the background is a bay in which a wooden English ship can be seen. Could it be that the English are arranging to “buy” Southampton? Sure looks like it. The number 1640 appears at the top. That’s when Southampton was “founded.”

Those most upset with this seal were, of course, the Shinnecocks, who have long claimed that this situation was a whole set-up, with the smiling settler on one side knowing this was in perfect English and the Indian having no clear idea of what was truly meant. However, 20 years ago, I recall other people were making a fuss who objected to how unclothed the Indian was. Southampton has its apparel laws. Couldn’t something be done?

It was pointed out that the Southampton Town Seal has long shown the same scene, except without the Indian. The Pilgrim faces the viewer, the ship over his left shoulder, and over his right shoulder the beach, where there is a boulder with a plaque on it indicating this is where these Englishmen came ashore for the first time.

Today, the Indian on the Village Seal faces the Pilgrim, but with pants and a vest.

That dispute was one of the things that energized the Shinnecock Indians to make their own seal, tribal leader Lance Gumbs confirms.

“We got tired of looking at that seal on garbage cans and other places in the village,” he recently told me. “So we decided to do something about it.”

In 2001, the tribe held a contest to create their own seal for the Shinnecock Indian Nation. In the end, they chose David Martine’s entry as the winner and so today, they display his very colorful and elaborate seal for the Shinnecock Indian Nation prominently everywhere, including on the billboard on the Sunrise Highway that sits on the property they own near the Shinnecock Canal.

It shows two fully dressed Shinnecocks in Native American garb, facing a drawing of a giant tortoise in the center, the 13 sections of its shell indicating the 13 tribes of Long Island. The words around it read “The Great Seal of Shinnecock Indian Nation” and the words “Algonquian” and “Always Sovereign.”

This seal was officially adopted in 2006, was unveiled at Southampton Town Hall in 2008, appeared in the paperwork when the Shinnecocks received their federal recognition in 2010 and it made another appearance just this past week when Southampton Town Supervisor Jay Schneiderman announced new ordinances that would protect Shinnecock Indian burial sites when building construction workers came upon them.