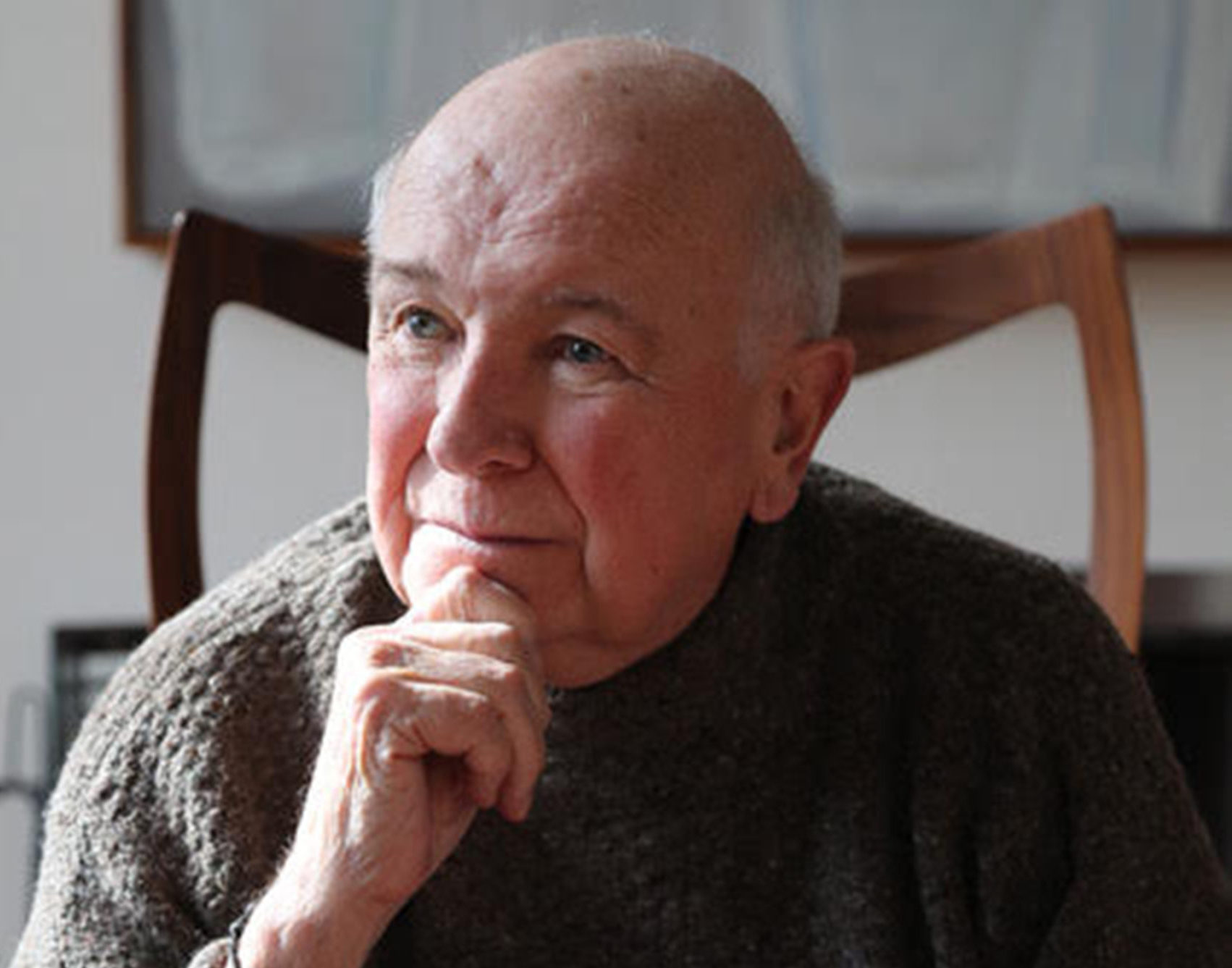

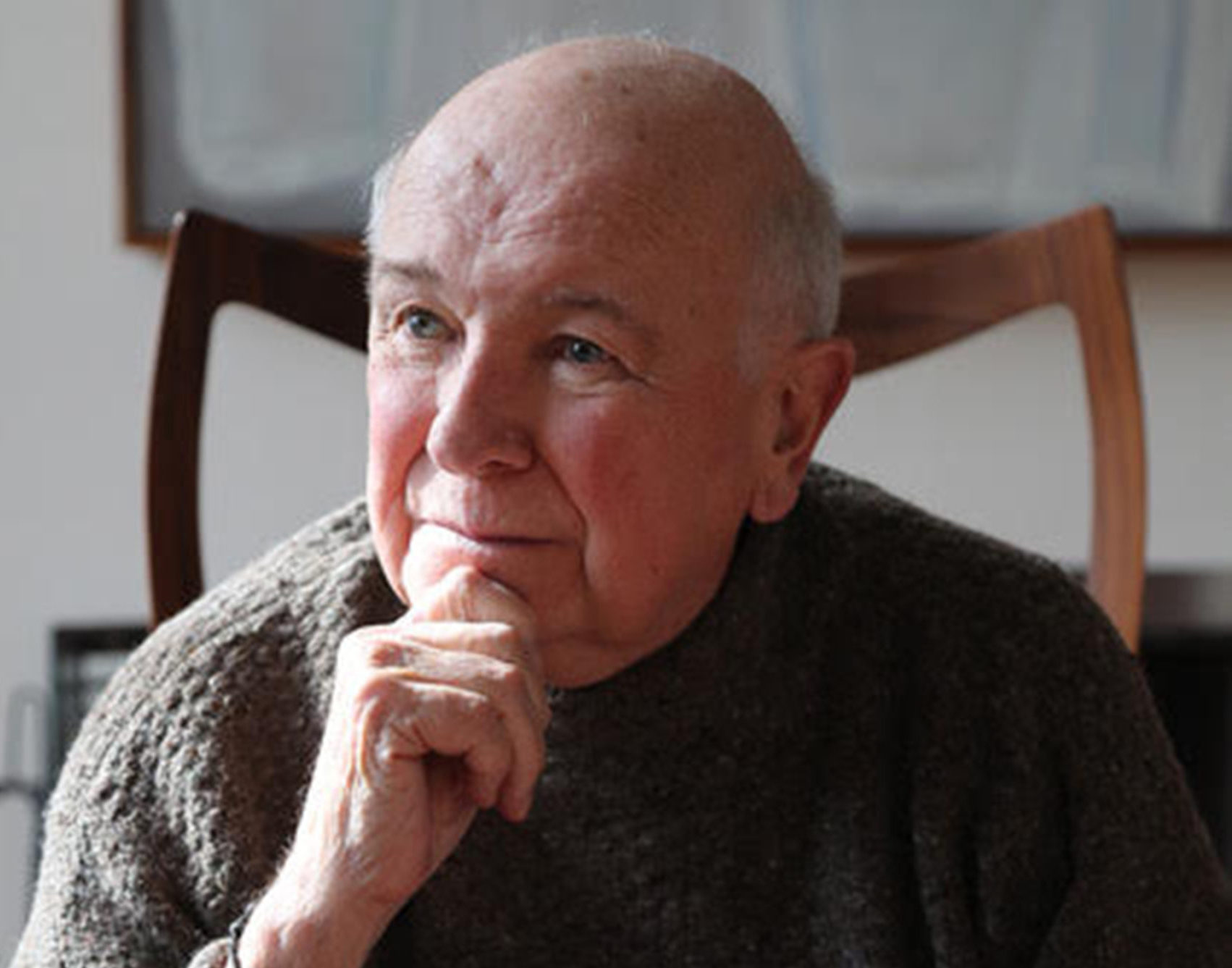

Terrence McNally, 81

Another bright light went out on Broadway on March 24 with the death of prolific playwright and Water Mill resident Terrence McNally, who died of COVID-19-related complications at age 81 in Sarasota, Florida.

McNally’s contributions to the American theater canon were vast, as were his contributions to the LGBTQ+ community, with his plays and musicals some of the first to explore themes like homophobia, same-sex romance, the AIDS pandemic, and gay pride.

His accolades include multiple Drama Desk, Lucille Lortel, Obie, and Tony awards, the latter for his plays “Love! Valour! Compassion!” and “Master Class,” his book of the musicals “Ragtime” and “Kiss of the Spider Woman;” as well as an Emmy (for “Andre’s Mother”); two lifetime achievement awards (including an honorary Tony award just last year); and induction to both the American Theatre Hall of Fame and the American Academy of Arts and Letters.

His other beloved and respected works include plays “Lips Together, Teeth Apart,” “The Ritz,” “It’s Only a Play,” “Mothers and Sons,” and the book of the musicals “The Full Monty,” “The Visit,” “Catch Me if You Can,” and “Anastasia,” as well as several operas and films.

Locally, McNally was honored by the Hamptons Doc Fest in 2018, when the opening film was “Every Act Of Life,” a documentary about McNally.

McNally was born in St. Petersburg, Florida to Dorothy and Hubert McNally, and raised in Corpus Christi, Texas (from which his most controversial play, “Corpus Christi” — featuring Jesus as a gay Texan — draws its name). He graduated Phi Beta Kappa from Columbia University in 1960 with an English degree, before moving to Mexico and then New York City, where he worked as a guardian and tutor for the children of John and Elaine Steinbeck.

McNally wrote his first Broadway play in 1965 at age 23, “And Things That Go Bump in the Night,” which closed after three weeks; in 1968, his musical adaptation of Steinbeck’s “East of Eden” (called “Here’s Where I Belong”) closed after one night.

But McNally was not to be deterred. Starting in 1969, he wrote a stream of successful plays, culminating in his breakout, “Frankie and Johnny in the Clair de Lune,” which was later adapted into a film starring Al Pacino and Michelle Pfeiffer. Eventually, McNally rooted himself in the Manhattan Theatre Club, a nonprofit off-Broadway theater which produced every play McNally wrote for 13 years. McNally had expressed gratitude to the Manhattan Theatre Club for its “unconditional love.”

His early years in New York were spent in a relationship with famed playwright and Montauk resident Edward Albee, whom McNally had met in college, but the couple parted due to differing views about their sexuality, with Albee hiding his so as not to be defined by it, and McNally shouting his loudly and proudly.

In 2000, McNally lost his longtime partner Gary Bonasorte to AIDS, which impacted his writing profoundly. In 2003, however, McNally entered into a civil union with his husband-to-be, Tom Kirdahy, a Broadway producer and former civil rights attorney for not-for-profit AIDS organizations. They met during a panel discussion Kirdahy was producing for the former East End Gay Organization at Guild Hall in East Hampton in 2001; the two were officially married in 2010.

Tributes to McNally’s life and work have been emerging from every corner of Broadway, including from Lin-Manuel Miranda, Tom Kitt, Audra McDonald, David Yazbek, and Chita Rivera, who starred in all three of McNally’s collaborations with Kander and Ebb.

Esteemed designer and former Sag Harbor resident Tony Walton, who designed the sets for McNally’s co-written play “House,” which premiered at the Bay Street Theater, shared a fond recollection of being in the audience of “Master Class,” and witnessing an historical Broadway moment of Patti LuPone getting a full-on standing ovation at the intermission. Of working with McNally, Walton described the experience as “one of my most treasured theatrical memories. He was truly one of the last great theatrical gentlemen,” he said, speaking both of McNally’s writing, and his gentle nature. “Plus,” Walton noted, “he was the ultimate pro.”

McNally is survived by Kirdahy, his brother Peter, and his own immortal words, which will continue to be performed and cherished for as long as theater lives.