1918 Influenza Invades New York City

In early July 1918, a heavy rain fell on the northern Belgium region of Flanders, about the size of Connecticut, that was the stage of battle after bloody battle during the four years of what was then called “The War to End All Wars.” On July 12, Philip Gibbs, a war correspondent for The New York Times, wrote about the lakes between Passchendaele and Ypres, where feet got stuck and guns jammed. “Anything that is bad for the enemy just now is good for us,” he wrote.

Journalists were not expected to be impartial observers and reporters of fact during World War I. The United States had thrown its lot in with the Allied Forces in April 1917. Germany was the chief antagonist on the other side.

Typhus was spreading through the German ranks, but it was what scientists now label the H1N1 virus, commonly known then as the Spanish flu, that was decimating the German army. It was also called “grip” or “grippe,” a name frequently used in The New York Times. Switzerland and Spain remained neutral throughout the war, and free reporting out of Spain made it seem like that was where the disease originated, hence the name.

The day after Gibbs’s report was published, the newspaper ran a story with the headline: “Germans Die Of Hunger: Malady Described as Influenza Is Really Due to Starvation.”

The claim that the disease was caused by malnutrition continued to be propagated by both military and civilian officials through The New York Times, even as the pandemic worsened.

This series incorrectly stated last week that news of the pandemic never made The Times’ front page during the war. In fact, on August 14, New Yorkers woke up to the following headline: “SPANISH INFLUENZA HERE, SHIP MEN SAY. Officers of Norwegian Liner Attribute Four Deaths During Voyage to the Disease.”

Four were reported to have died aboard the Norwegian steamship.

“10 OTHER PASSENGERS ILL: Brooklyn Doctor Who Is Treating Them Says They Are Suffering with Pneumonia. 200 Passengers Ill at One Time. Health Officer Passed Ship.”

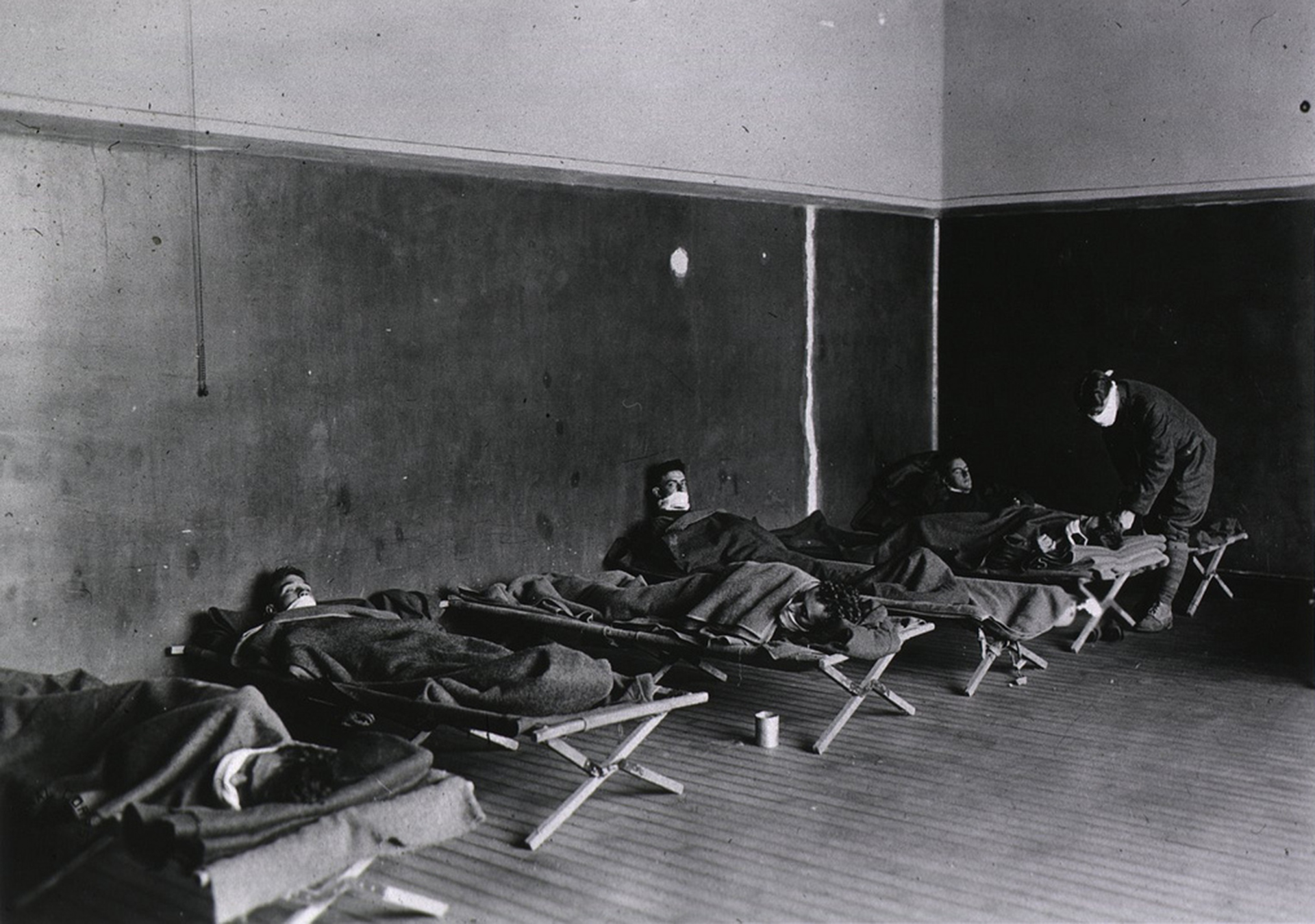

The disease was likely already in New York City by that time. The H1N1 virus had been breaking out in military camps across the country, including bases in the New York metropolitan area, including Camp Upton in Yaphank, and Camp Mills in Garden City. The earliest known outbreak occurred in Fort Riley, Kansas on March 4. Soldiers going home on leave from various bases brought the highly-contagious disease with them.

But the arrival of the Norwegian vessel was the first time New York residents were alerted to the possibility the disease was here. The Times repeatedly downplayed the idea that the deaths on the ship had been caused by the influenza, suggesting that all those taken ill were suffering from pneumonia.

Allowing the ship to dock and the passengers and crew to disembark without being quarantined was the first in a long series of blunders made by New York City health officials. The Times reported: “The cases of mysterious illness were reported to the health officer by the surgeon when the steamship arrived at the quarantine station yesterday, and he did not regard the disease as contagious for healthy persons evidentially because he had permitted the vessel to go to her pier.”

The article concluded with a report of arrivers from a different ship. “‘C. Stanley King, who arrived here yesterday from England, after being abroad doing war work since last December, contracted the Spanish influenza in England and lost nearly forty pounds in weight. The Spanish flu, as it is called in England for short,’ Mr. King said, ‘has spread all over the country, and caused schools, factories, and even shipyards to suspend work on account of the great number of pupils and workmen that have been laid up by it.’”

The piece again asserted the United State’s immunity, despite the ill passengers aboard the Norwegian ship. “The American soldiers have not yet been affected by the disease very much, which the medical experts put down to the fact that their physical condition was so good they were able to throw the germs off.”

King, who described falling ill with fever, weakness, and delirium, and his fellow passengers were also not quarantined.

The 1918 influenza pandemic, or H1N1 virus, has genes most likley of avian origin. Although there is no universal consensus regarding where it originated, it was first identified in military personnel in spring 1918, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. It is estimated about 500 million people, or one-third of the world’s population, became infected with the virus. The number of deaths was estimated to be at least 50 million worldwide, with about 675,000 occurring in the United States.

Next week, this series will focus on the H1N1’s devastation in New York, and its spread to Long Island.

t.e@indyeastend.com