War Effort Exacerbated 1918 Pandemic

This is part three of an ongoing series on the H1N1 influenza A virus that killed 675,000 Americans between 1918 and 1919. We are telling the story, as much as possible, through the words of reporters of the time, from either The New York Times archives or newspapers on the East End, such as The East Hampton Star.

Over there, over there,

Send the word, send the word over there

That the Yanks are coming, the Yanks are coming

The drums rum-tumming everywhere.

So prepare, say a prayer,

Send the word, send the word to beware

We’ll be over, we’re coming over,

And we won’t come back till it’s over, over there.

-George M. Cohan, 1917

By August 16, 1918, the tide of World War I was beginning to shift decisively in favor of the allies, whose efforts were bolstered by the ever-increasing influx of American troops onto the battlefield.

The banner headline across The New York Times’s front page that day trumpeted recent victories, along with a call to yet more arms: “British Take Two Towns Above Roye, French Gain On Oise; Our Troops Reach Vladivostok, British In Caucasus; ‘Send 4,000,000 To France And Win The War,’ Says March.”

Across the Atlantic, the viral disease commonly known at the time as Spanish Influenza, flu Grip, or Grippe was establishing a foothold in New York City. The growing crisis was not helped by the fact that ocean liners from Europe were discharging infected passengers into the city on an almost daily basis.

On page 16 of The Times that day, a headline read: “Liner Had Five Deaths Due to Influenza,” followed by the subhead: “Eleven New Cases Arrive on Another Ship, but Authorities are Not Alarmed,” then, in all caps: “NO FEAR OF AN EPIDEMIC,” followed by: “Health Officer of the Port Says He Does Not Intend to Quarantine Against the Disease.”

The first sentence of the article read: “Eleven more cases of Spanish influenza, or whatever it is, were reported at quarantine yesterday from a ship arriving from one of the Scandinavian countries.”

The Times reported that most of the passengers aboard the ship on which the deaths occurred were Dutch, and that the deceased were all East Indian, who had been traveling in steerage. The five bodies were buried at sea. About 200 passengers became ill on that trans-Atlantic journey.

Colonel J. M. Kennedy of the U.S. Medical Corps was the chief surgeon of the New York Port of Embarkation. He explained to The Times why he was not quarantining the ship nor any ships on which passengers had died after contracting influenza.

“It would be utterly impractical to establish a quarantine at this port against this disease,” Kennedy said. “We can’t stop the war on account of Spanish or any other kind of influenza. To quarantine against it would mean to isolate the patients somewhere and fumigate every ship. That would clog the harbor and produce interminable delays in the sending of troops and supplies overseas, and that cannot be permitted.”

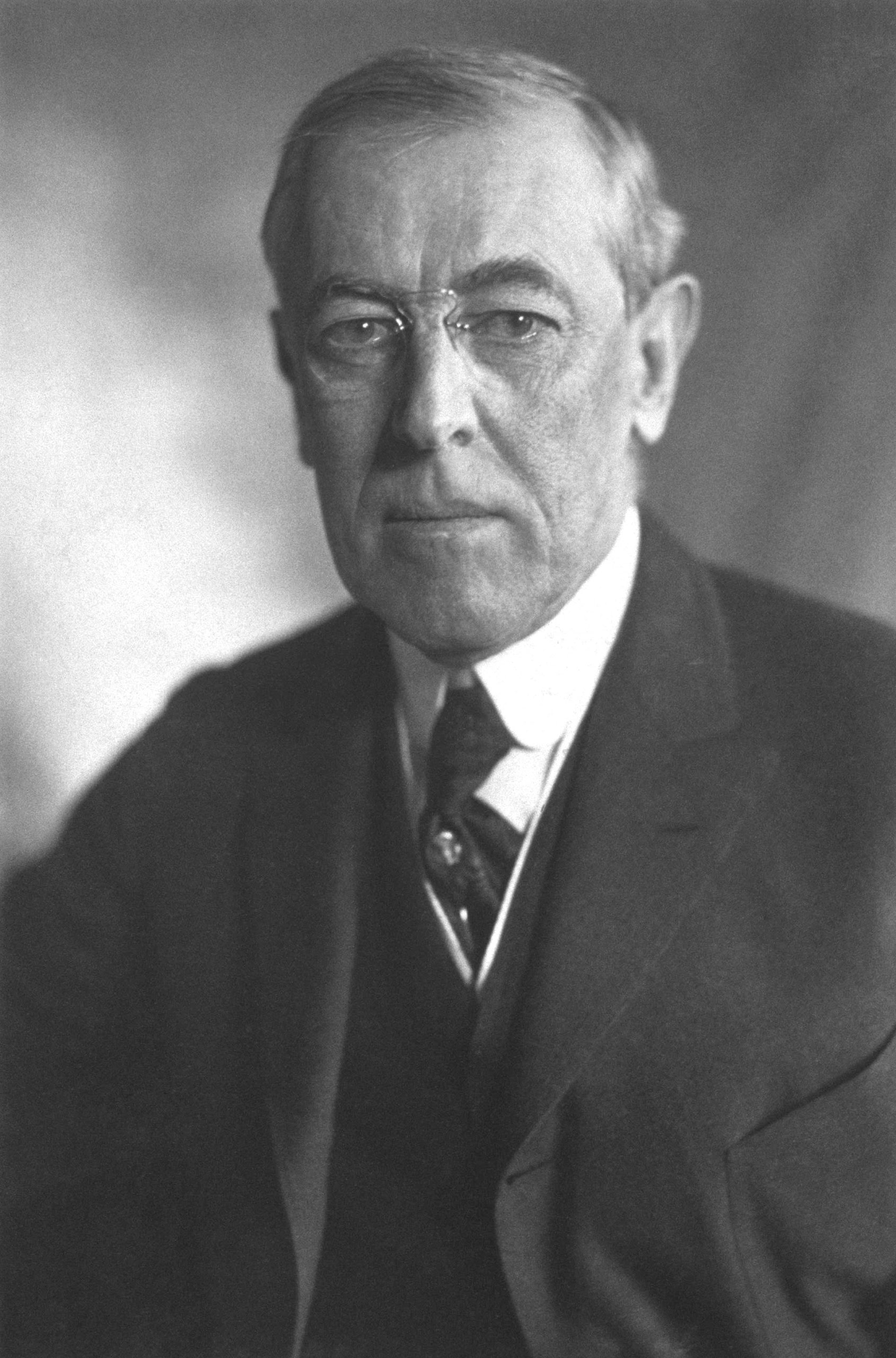

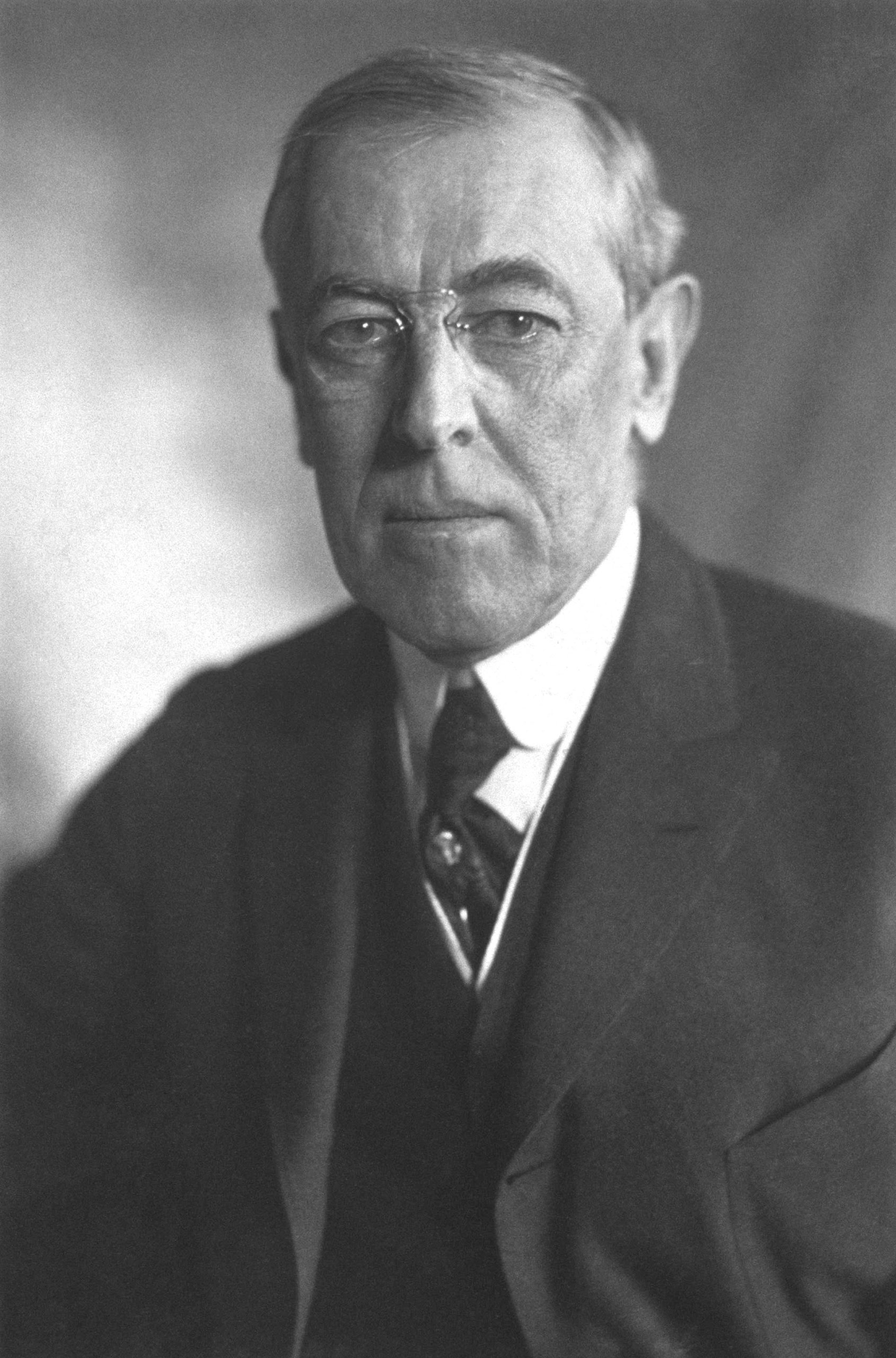

Michael Beschloss, a historian who has written nine books on the U.S. presidency, blames the White House and its lack of federal leadership and empathy for what quickly turned into a pandemic. On April 24, 2020, on “Meet the Press Daily” on MSNBC, Beschloss said Woodrow Wilson is “a monumental negative example of how not to be president during a pandemic.”

“The influenza began among American soldiers,” Beschloss told host Chuck Todd. “President Wilson was privately told, ‘Don’t put them in close quarters, don’t send them to Europe, they will infect one another and they will spread it through the populations of Europe.’ Instead, he put them in close quarters on ships that were called ‘coffin ships,’ because so many people died.”

Despite America ultimately losing 675,000 lives to the disease, Wilson never made one speech about the pandemic to the American people.

“He thought it would be bad for the morale of Americans during World War I,” Beschloss said. “That is just about as bad as you can be as president.”

The historian said beyond a lack of empathy, Wilson’s failure to lead “did not allow Americans to protect themselves in a way that he would have if he were to have said: ‘Here is the magnitude of the problem. This is what you can do to make sure your family is safe.’”

With little leadership at the federal level, New York was on its own. Dr. Royal S. Copeland was New York City’s health commissioner. On August 20, he told The Times that his department had found very few cases of the virus, and those they found were of mild form.

Ships continued to arrive with sick passengers, and on September 13, on page 7, an article in The Times assured New Yorkers with a story headlined: “City Is Not In Danger From Spanish Grip.” The lead sentence read: “Although 25 cases of Spanish influenza were recently taken from a ship arriving at New York, persons in this city are in no danger of an epidemic, according to Dr. Royal S. Copeland.”

Within a week, major outbreaks of the disease were reported at two army bases — Fort Devens in Ayer, Massachusetts, and Camp Upton in Yaphank.

On September 20, the first reference in The East Hampton Star to the virus appeared on page 3. It was a single sentence in the column called Brief Notes from Amagansett: “Geo. V. Schellinger has been sick for several days with influenza.”

On September 24, on page 9, The Times reported 114 new cases in the city, and 65 deaths from the disease at Fort Devens.

To combat the virus, Copeland told The Times isolation was not needed. Instead, 10,000 signs were positioned in subway and elevated train cars, and in trolleys across the city, as well as in theaters that read: “To prevent the spread of Spanish influenza, sneeze, cough, or expectorate (if you must) in your handkerchief. You are in no danger if everyone heeds this warning.”

This is part of a series on the influenza 1918 pandemic. Read the first part here.

Next week: The Times begins to run a daily scoreboard to keep track of reported new cases and deaths as health officials continue to refuse to shut down the city, while the virus continued to spread there and across Long Island.

t.e@indyeastend.com