A Comical Look At ‘The Mueller Report’

Comic book artist and writer Barbara Slate’s latest graphic novel, “The Mueller Report” came out right before the pandemic, which just about eclipsed all other news. But then, this past April, one year after the Mueller Report was published, the Supreme Court announced a block on the release of redacted portions as requested by the House Judiciary Committee. So back it is to Mueller’s two-part investigation into allegations of Russian interference in the 2016 Presidential Election, and obstruction of justice.

But how many people slogged through the report’s 448 pages of dense legalisms and ambiguous, guarded conclusions? Not a lot, I’d bet. For sure, though, Slate read the report, word for word, some parts repeatedly.

For sure, also, her slim visual adaptation can lay claim to providing a public service because most of us will never (completely) read the original report, a complex and at times daunting detailed inquiry. So, here is a version of the report, in two parts, just like Mueller’s, and in the form of comic-book panels that present direct quotation from the report, as well as copies of emails, tweets, and official documents. There are also talk (and thought) bubbles that mimic exchanges between the major players whom Slate captures with minimal strokes and subdued expressions. A “cast of characters,” alphabetically arranged, is helpfully included at the end.

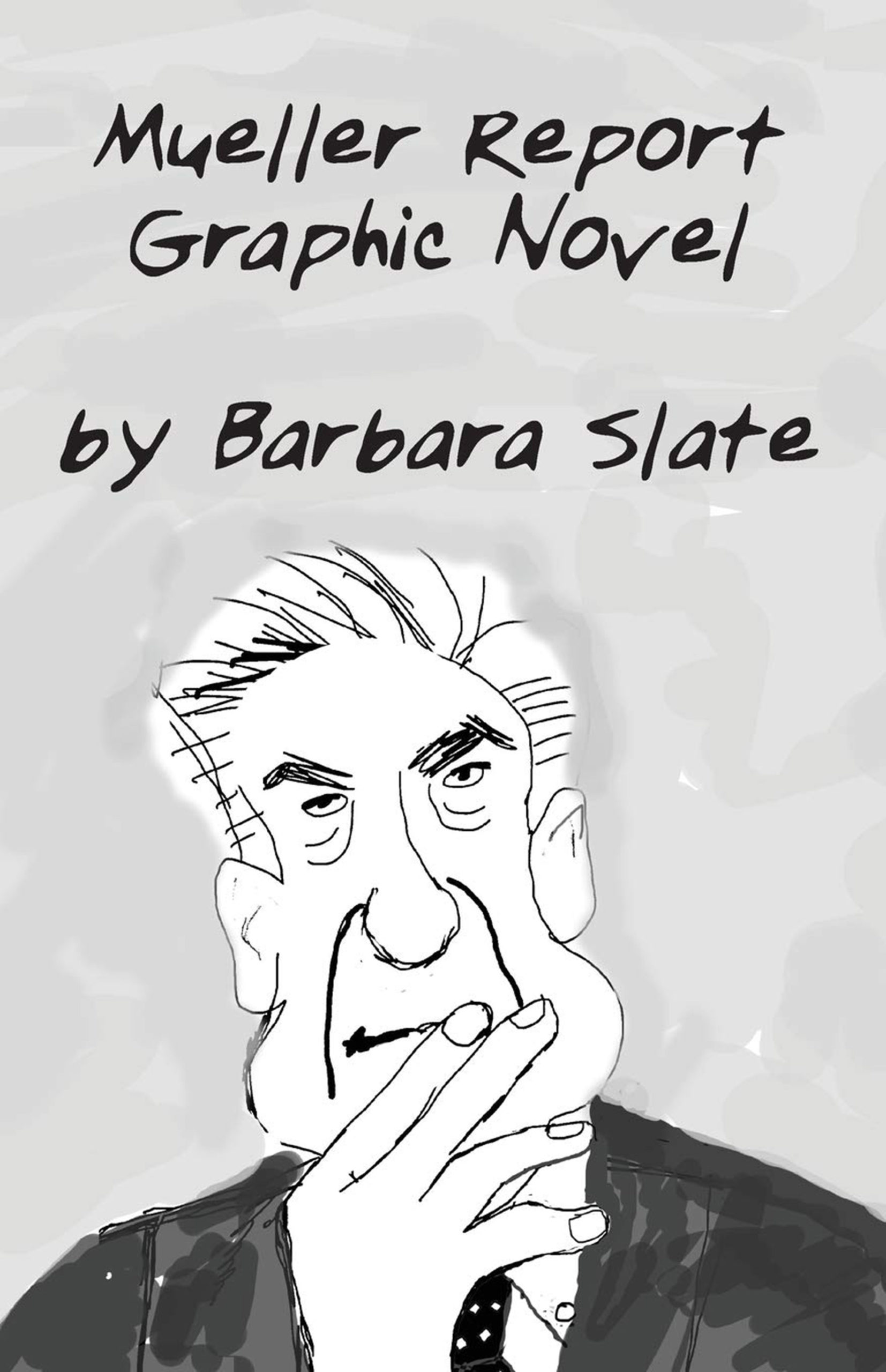

A reader has to marvel at Slate’s almost neutral depictions, especially of Mueller, whose pensive expression, fingers on lips, adorns the cover of the book, and whose slightly satisfied look appears at the end, as he testified before the House Judiciary Committee last July, his closing words set off with three horizontal rectangles that encase the report’s conclusion: “1) If we had had confidence that the President clearly did not commit a crime, we would have said so; 2) Charging the President with a crime was not an option we could consider. You cannot charge a sitting president. It is unconstitutional; 3) And I will close by reiterating the central allegation of our indictments, that there were multiple, systematic efforts to interfere in our election. And that allegation deserves the attention of every American.”

A lone rectangle, on the opposite page, though, emphasizes what Slate wants readers to know and remember: “Obstruction of justice is punishable whether or not an underlying crime has been committed.” This reminder, as the Presidential election season heats up amid demonstrated attempts to revisit absentee mail voting, could not be more timely or significant.

Slate wants not just to remind readers of events that prompted the Mueller inquiry but to inform with an entertaining, easy-to-follow narrative, including the now heightened awareness of the redacted portions of the Mueller Report which here stand out as empty black space. To that end, she developed a “new drawing style” (one she had started with a memoir in mind) that was different from her other comic-book work. The cast of characters was the most “challenging,” she writes, but luckily, so many figures seemed “out of central casting,” or immediately recognizable, especially Trump’s open bud-mouthed look, eyes closed, hair sloping down. In one panel, he and James Comey, the former and dismissed director of the FBI, are having hamburgers — Comey’s regular, the President’s, a double.

Slate, an award-winning, nationally known illustrator and cartoonist for both mainstream and alternative media, has an impressive, extended resume that includes a long career with DC and Marvel comics, Disney and animated segments for NBC’s “Today” show, and her late ’70s strip Ms. Liz, a feminist cartoon character, ran for several seasons in Cosmopolitan. She is one of only a few women cartoonists to have entered and prevailed in a male-dominated field. Though she did Betty and Veronica stories for Archie comics, her more sophisticated work includes strips and graphic novels that feature strong, successful women. Her professional life embraces teaching as well, including a course she has given at Cooper Union called “You Can Do a Graphic Novel.” East End art lovers may also remember her work on exhibit at the Benson Gallery and Guild Hall.

Though critics may cavil that Slate’s selected text takes quotations out of context, much media commentary on the Mueller Report noted that very problem in Attorney General William Barr’s preemptive “summary” of Mueller. The irony of Slate’s version is that in this condensed, compressed form, the Mueller Report becomes accessible and understandable. And, though sympathetic to reasons for the investigation in the first place, Slate manages a passionate but restrained critique, hoping that citizens will not only be “more informed” after reading her graphic novel but also motivated to read the original and perhaps now mull over the recent decision to suppress redacted passages.

Somehow, I think Robert Mueller III himself might be pleased at what she accomplished.