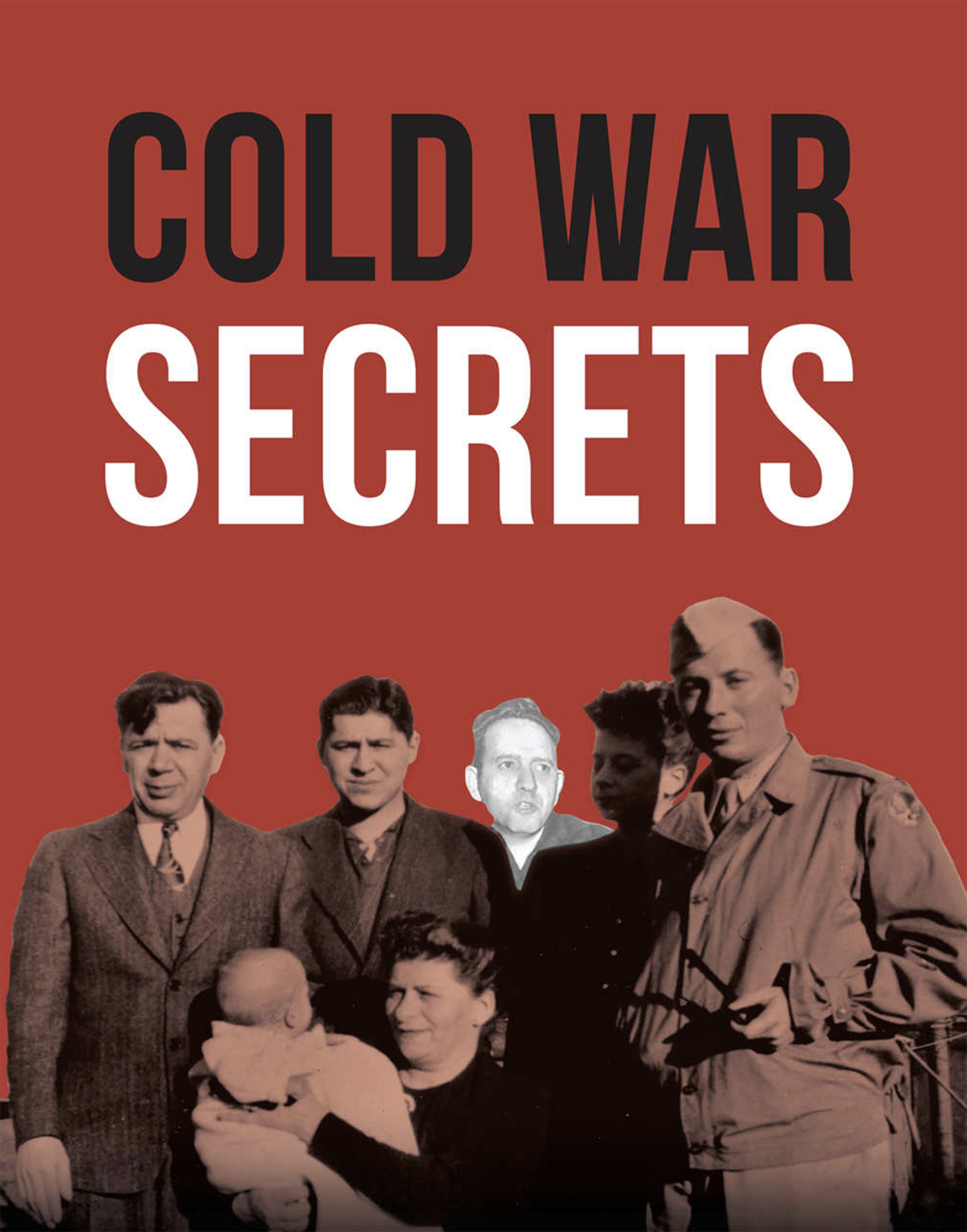

Investigating ‘Cold War Secrets’

Paul Pitcoff’s memoir “Cold War Secrets,” is well worth reading, informative about when Communist witch-hunts dominated politics and ruined lives, a time Arthur Miller once called, along with The Great Depression, one of the two most frightening events in mid-20th Century America. But “Cold War Secrets” is also a moving, sharply observed, sensitive remembrance of childhood, adolescence, and early manhood that defies easy expectations.

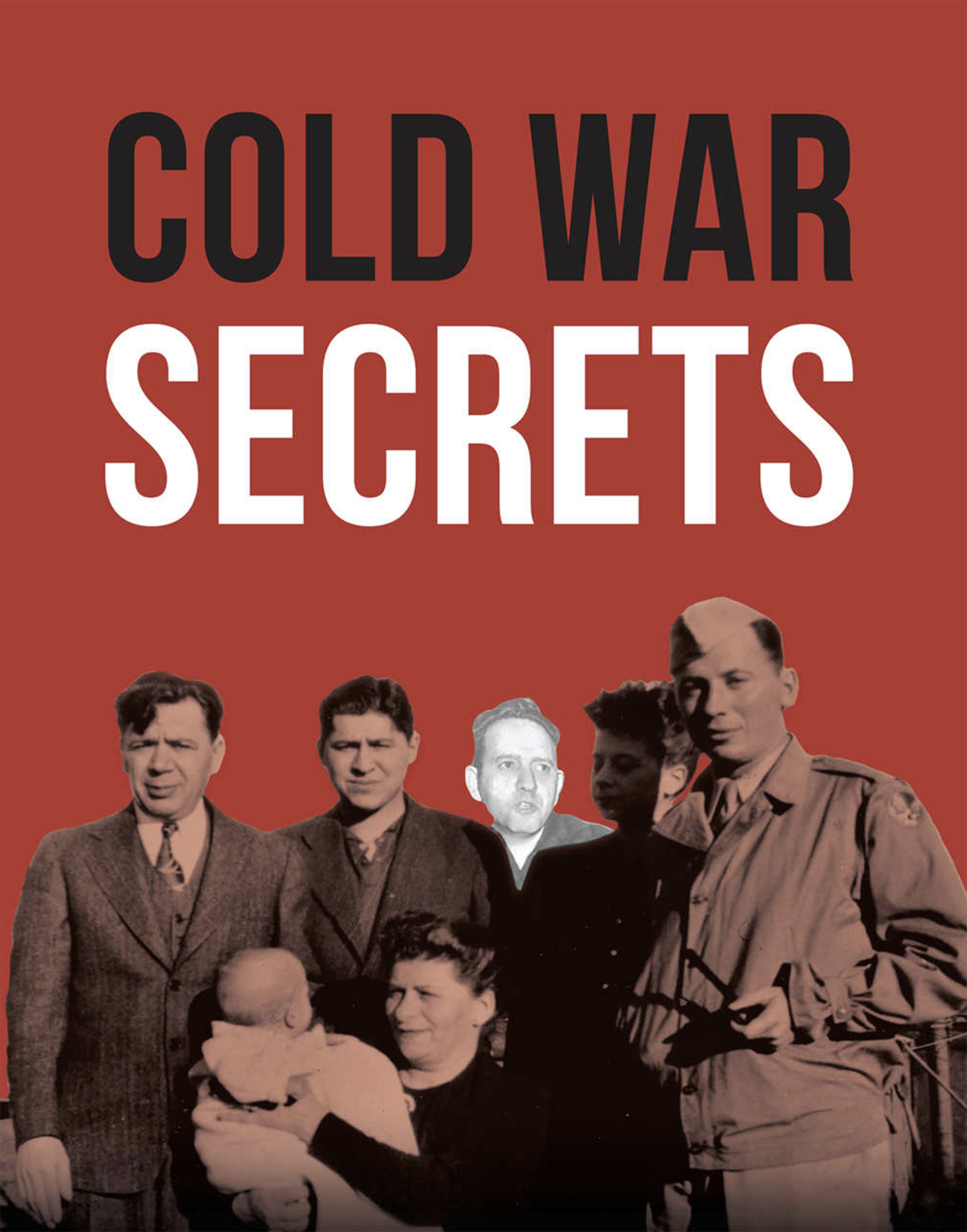

A charmingly self-deprecating account of growing up in the Bronx, the book features Pitcoff as the only child of an intelligent couple whose often mysterious, contradictory behavior and odd advice confuse him, though he knows he’s loved. A short prologue sets the stage for what follows. Young Paul is getting ready to play stickball when the doorbell rings. Two large, identically dressed men, flash badges, and ask for his father. It’s the FBI. His father, Robert, isn’t home, and his wary mother, smoking her way through nervousness, tells Paul that they just “dropped by” because “they happened to be in the neighborhood.” End of explanation. And inquiry.

Paul intuits a “don’t ask, don’t tell” way of life in his home, but, with age and acuity, he becomes increasingly aware of secrets in his parents’ lives and, just as significant, of being somehow complicit by not pushing to find out. His Russian-born father, he knows, had been a Communist but wound up a fanatical anti-Communist, even, to Paul’s chagrin, testifying before HUAC (The House UnAmerican Activities Committee). An Eisenhower Republican, his father nonetheless sent Paul to schools and camps associated with the labor-movement left, and all his life acted vigorously on behalf of equality and social justice.

Paul’s mother, who “dumped” him onto various mentors to pursue a career in social work, was “formidable.” Among her many strong-arm achievements was getting Paul into Stuyvesant High School, even though he failed the entrance exam. But then she continued to ignore him as he made his tentative way among the toughs in the neighborhood. It’s his father, though, who particularly fascinates him — missing from an early family photograph, an autodidact intellectual, and a master of many trades.

What engages the reader throughout, as scenes change and the years go by, is the author’s modest, bumbling attempts to live according to his father’s mantra: Don’t trust authority, find out for yourself. It meant for young Paul taking risks, some of them dangerously adventurous, such as when, barely 20, he volunteers to go to Arctic Finland to help farmers homestead, a harsh time during which he somehow gets himself a lovely girlfriend. What he does not (yet) appreciate are the risks that his parents took in living the way they did, including having him. Or how, beneath a sometimes-comedic rendering of tense family meal times or argumentative hours spent with his parents’ political friends, his father and mother in their lackadaisical guidance did, by default, lay out a path for him, albeit an unguided and often unprotected one. He learned confidence.

But he always remained ambivalent about his own “diverse careers, friends, and experiences.” Was he an idealist, pragmatist, participant, observer? He had been a documentary filmmaker, an academic who started the Department of Communications at Adelphi University, an attorney, a program developer for teens in foster care. In his 60s, he was still asking himself what he wanted to do when he grew up. His sense of being “enveloped with uncertainty,” though it enabled him to avoid the “trap of dogmatism,” also extended to his writing a memoir. A challenge to document what he had begun to learn about his father led him to dig for more.

He concludes: “After years of ponderings and research I have come to believe that my parents wanted their story told, but didn’t know how to break through some inner conflict. Thus, they left me only a trail of bread crumbs.” In “Cold War Secrets,” Pitcoff tracks those crumbs to their surprising source, and perhaps (unintentionally?) leaves some of his own.