The Last Pandemic: How the Hamptons Weathered the 1918 Spanish Flu

On the morning of Thursday, December 12, 1918, the residents of Southampton picked up the new copy of The Southampton Press to read a report of the goings on in that town for the prior week.

The front page had a story about the Village President.

“After a brave fight for over a week against the ravages of Influenza and Pneumonia, Village President Charles Elmer Smith, age 39, died at his home in Hampton Road.”

Mr. Smith was born in Boles, Missouri, came to Southampton and never left. He worked at first as a carpenter, then later became a respected home builder. The trustees would be his pall bearers.

There were other stories about the epidemic on the front page of The Southampton Press that day. One of them involved the death of a 17-year-old girl. She had graduated Plattsburgh Normal High School in upstate New York and had answered an ad to be an assistant teacher at Southampton High School in the fall of 1918. Her name was Helen Bond, and she had come down here in the summer to study and get ready for her job at the school. She was vivacious, full of life and much loved. After just a few weeks into her teaching assignment, however, she fell ill and went back home upstate. Now a report had come down from Plattsburgh that she had died. This was a big blow.

That December 12, the newspaper also announced on its front page the cancellation of all future Red Cross women’s sewing bees, where clothes were sewn for the war-stricken refugees in Europe. (World War I’s fighting had just come to a halt.) They also sewed “pneumonia jackets” for the American troops suffering illnesses still in place on the front lines.

“During the quarantine which has become so necessary on account of the influenza,” the newspaper wrote, “we do not feel we should ask our women to assemble in the workroom even for th(is) very important sewing.”

But the newspaper did offer hope. “Vaccines against the organisms of complicating pneumonia (in Europe) are being used in some places, particularly in the cantonments, and there is reason to suppose that they may prove of value.”

They did not. This deadly flu lingered on and on unchecked, right through Christmas and as far along as the following April. And then a less-frightening version of it came back in the winter of 1919–1920.

The Southampton Press also reported that Lion Gardiner, a descendent of the Lion Gardiner who settled Gardiners Island in 1639, had died of the virus in Quogue the prior week.

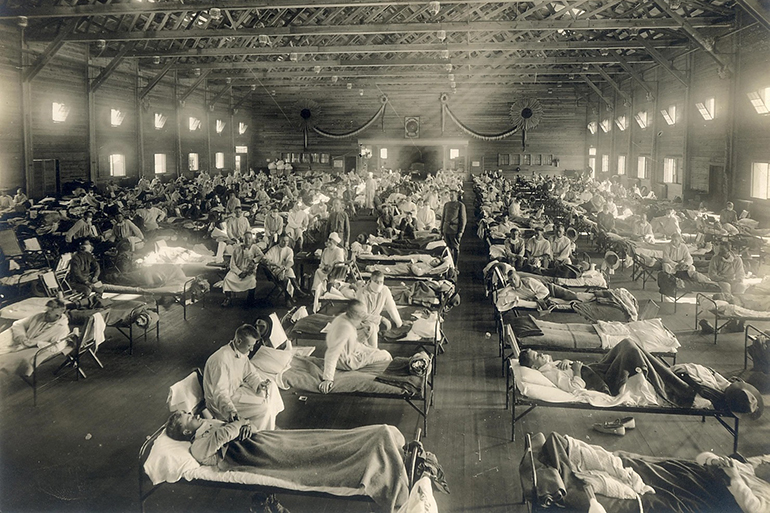

Today, experts believe about 500 million people caught that deadly disease—about one of every three people on earth at that time—and that as many as 50 million people died of it. There is disagreement among historians about where it started. It was known that in the U.S., there had been an outbreak at an army base in Kansas in March 1917. But there was an earlier outbreak in France at an English army base in 1916.

Some people thought it must have started in Germany. It was called the China Flu in Russia and the French Flu in Spain. Even today, nobody knows its source. In the end, it came to be known as the Spanish Flu, named that because the Spanish press was not confined by the censorship that affected other nations during WWI. Thus, the proliferation of news from Spain about the flu’s worldwide spread led many to associate the virus with that country.

Earlier in the spring of 1918, there were indications that this flu, which was ravaging the troops in Europe, had come to America.

In its “Summer Cottages” section on May 15, 1918, the Press noted that “Goodhue Livingston, a prominent summer person, was reported ill with it and staying in his New York City townhouse at 38 East 65th Street until, hopefully, he would recover.”

It was a full-raging epidemic by September.

An item in that October 17 issue stated Dr. Hugh Halsey, a Southampton doctor, was suffering from influenza but was now recovering. And Dr. John Nugent, another Southampton physician, had been confined to his home since Tuesday.

In that same issue, the Press published a statement from Dr. Hermann M. Biggs, State Commissioner of Health, that the number of people getting sick was expected to decline within a few weeks.

He was wrong.

Then there was this. “There are many cases among the school children and the prompt action of the Board of Health in closing the schools is commended by all….The epidemic is general all over the Island, especially virulent in the Eastern states, New York and New Jersey, and is rapidly spreading through the west.

“For the treatment of secondary pneumonia, a serum is available… Calls for additional physicians and nurses are still being received from all parts of the State and are being responded to as rapidly as possible.”

Six weeks earlier, the Village had ordered the closing of not only all the schools, but the banning of assemblies of people in churches and other public places.

On October 30, a letter to The Sag Harbor Express came from U.S. Navy Officer Peter Hughes PRIR 1st Class, languishing in tight quarters aboard a troop ship at the Navy wharf in Virginia Beach.

“It is a crying shame that we have to lose so many American boys when they are so far superior to the enemy’s men—but that is probably one of the ideas General Sherman had when he let go his famous saying. (“War is Hell”).

“We have been under strict quarantine here for over two weeks now on account of the ‘Spanish Influenza’ and judging from reports, you have been having a touch of it in the Harbor. It spread very fast here, and I do not know how long they will keep us cooped up like a lot of chickens.”

This pandemic from almost exactly 100 years ago was as horrible as the COVID-19 today, but it was not front-and-center in your face all day with reporters and experts telling story after story, relentlessly terrifying everybody 24/7. The weekly paper was the media here.

There was no radio. No TV. No internet. No smartphones and no airplanes. And other than the train in and out of Manhattan to Southampton, the few thousand people living out here didn’t travel much. Most roads were dirt. Only a few people had automobiles, so transportation was in wagons or on horseback. People gossiped, had families and friends, worked the farms and fished the seas, then on Sundays went to church. The newspapers marked their births, marriages and deaths. And life went on.

For example, among many non-flu-related items in the December 12 edition of the Press was the story of Stanley Kominski, a Polish farmer from Riverhead who was sitting in his wagon, driving a team of horses across the railroad tracks, when the train came and hit the wagon broadside. The engineer screeched the train to a halt. On one side of the tracks were the two dead horses, the farm wagon split in two and the farmer’s hat. On the other side of the train was the farmer, bewildered but unharmed, who was looking for his hat. They gave it to him.

Early issues of The Southampton Press, The Sag Harbor Express and Dan’s Papers (which began publication in 1960) can be found at nyshistoricnewspapers.com. Reporting for this story came from that archive.