Lee Skolnick: Getting To The Church

It’s easy to imagine that when you’ve been in the architecture business for 40 years, you might get into a design rut of sorts. But no one could accuse Sag Harbor resident Lee Skolnick of SKOLNICK Architecture + Design Partnership of resting on his laurels.

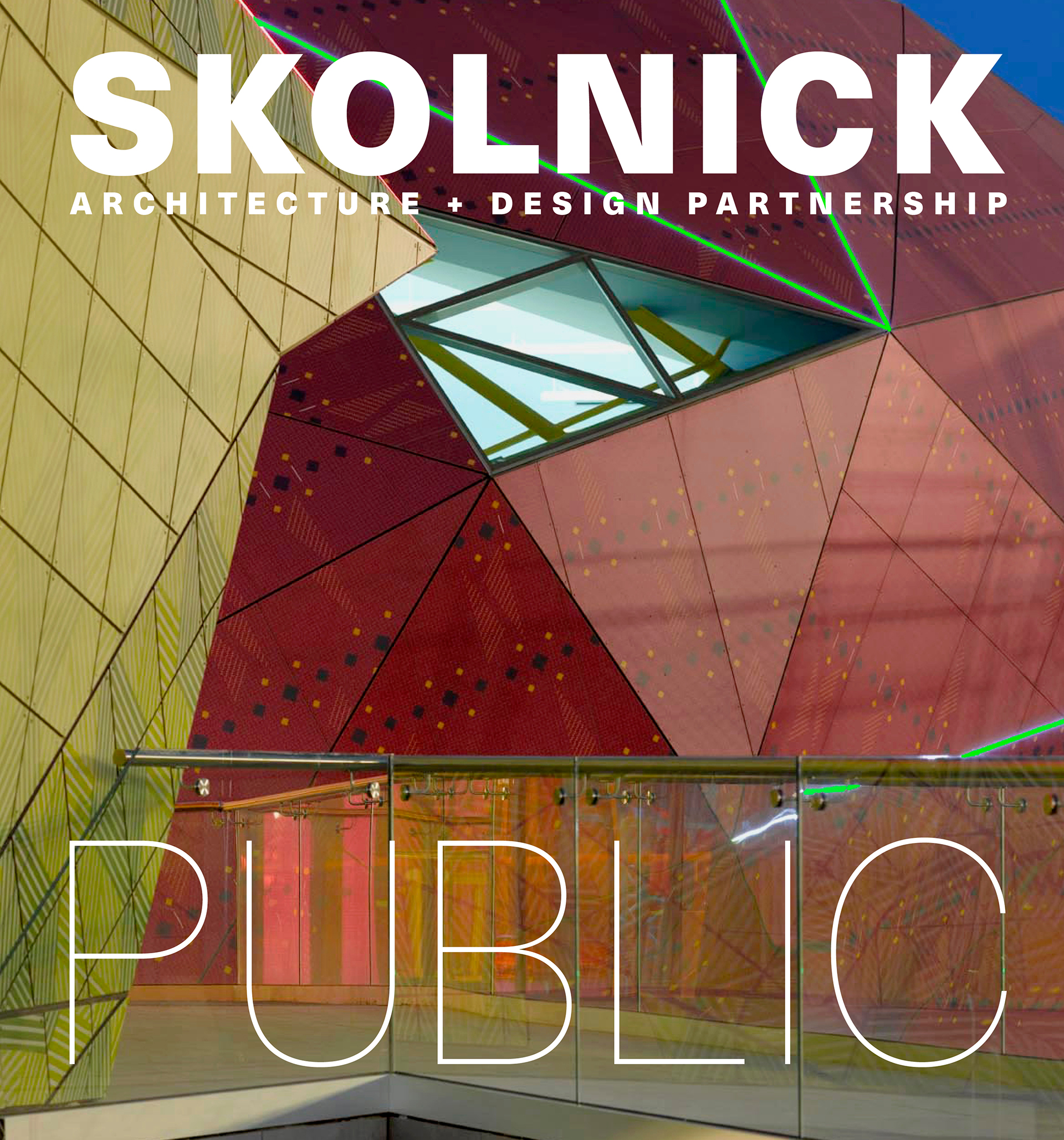

With a monograph being published this summer, “SKOLNICK Public/Private;” an upcoming accolade as Hamptons Cottage & Gardens’ 2020 Innovator award winner (previous winners include Richard Meier and Robert A.M. Stern); and the much-ballyhooed new Sag Harbor cultural center, The Church, under his belt, the Long Island AIA Lifetime Achievement Award winner discussed some of his past projects, both private and public.

Skolnick, along with his partners Jo Ann Secor and Paul Alter, has covered a wide spectrum of design, from ground-up projects like the Children’s Museum of the East End, to The Church, which was a reimagining of a building, and everything in between. His work is global and famous and totally original.

“What’s interesting, for me, in terms of my narrative, is that The Church is like a synthesis of all the things I’ve been doing out here for 40 years, because I’ve been doing a lot of homes with artists, but I’ve also been doing all these of community projects,” Skolnick said. “And here is a project where Eric and April and I have worked together doing something for the community” he added, referencing April Gornik and Eric Fischl, the philanthropic married couple who are both artists and socially active in Sag Harbor.

He said it was the right time for the project, as community is so important. “Nobody planned this, but it’s symbiotic that the community will come back together at some time, in venues and places like this one.”

What were the triumphs and pitfalls of working on an older building, for someone who is better known for his soaring modern edifices? “It’s a trifecta,” he said, laughing, “because on the one hand, the building has passed through several hands over the last few years, so temporary owners had started to adapt it, and some work had been done, but it didn’t really have anything to do with our plans and what we wanted to do.”

What intrigued him as an architect, he said, is that The Church “is a found object. You have to respond to a found object. It’s not like an empty piece of a land. It’s not ‘What do I want to say here?’” His vision, instead, needs to morph into the building that is already standing.

“You see this a lot in Europe,” Skolnick said. “Palaces, cathedrals, convents, you name it, where someone has come in and inserted something very contemporary without compromising the integrity of the historic structure. One of the great architects who was known for this was Carlos Scarpa; he did these tremendous interventions in historic buildings, and I really took a cue from that, because the whole dialogue becomes ‘what’s old is old; what’s new is new.’”

But it’s a whole new level at The Church. “The timber frame had never been exposed,” Skolnick said. “It had plaster walls, a plaster ceiling.” Uncovering the trusses — “oak timbers, solid oak timbers that span the sanctuary,” he said with something approaching reverence — “each piece is 50 feet long. The whole frame is exposed, it was covered up. You have this tremendous spiderweb with the beams exposed.” Adding a staircase and a glass elevator, however, is “thoroughly modern,” Skolnick said. “It’s really clear what is old and what is new, and it creates a kind of frisson which honors both the past and the present.”

The monograph, “SKOLNICK Public/Private,” soon due for release, is what we used to refer to as a topsy-turvy book, with two covers. One features the private residences the firm has designed, the other, the public places; 14 projects in all.

“My practice has always been schizophrenic and somewhat confusing to people,” he said, smiling. “I do all these houses, and my clients will see ‘museum’ in a magazine, and they’ll ask, ‘It says Skolnick, but that’s not you, right? And the same thing with our cultural clients, they’ll see a house in Architectural Digest, and they’ll say, ‘You don’t do houses, do you?’ So, this book is somewhat unique. I picked projects that tell the story of our evolution.”

Some current projects include a restoration on the Cedar Point lighthouse, and at LongHouse Reserve, where Skolnick is a first vice president. “I recently designed a master plan and education pavilion for the organization.” His first job in the area was renovating the Pollock-Krasner House and Study Center in Springs, “when Helen Harrison first took over there, because it was not handicapped accessible.”

So, he built some ramps? “Yeah, basically,” he said, chuckling. “Some ramps and a porch. A lot of my first work out here was porches, bathrooms, closets,” he shrugs, a modest man.

“I’m a musician; that was always my first love,” he said. He studied music theory at college, along with other liberal arts subjects like cinematography. “I had this existential crisis. But then I took an elective course in architectural theory and history, and it was the proverbial lightning strike. I read that to be an architect, one has to know everything. You have to synthesize it into what you do, and that just was so appealing.”

“I think the thing that hooked me on architecture,” he continued, “is that you end up with something physical. It impacts people’s lives, and maintains itself over time. Whether you’re doing a home for someone and you want to capture the essence of their lives, or whether you’re doing something for the community, you want to enhance the lives of people on a larger scale.”

“Right now, having had some time to reflect out here, I’ve become very interested in affordable housing,” said Skolnick, who added that he’s been in some exploratory discussions with the Powers That Be. “I think the biggest crime is that the people who grew up out here can’t afford to live out here, and the people who work out here and serve all of us have to drive 50 miles in traffic every day just to get to their jobs. It’s a crushing need,” he said, and “I want to present something to the towns to elevate the discourse. It’s the one glaring need out here.”

To learn more, visit www.skolnick.com.