Over 16,000 In NYC Die In A Month

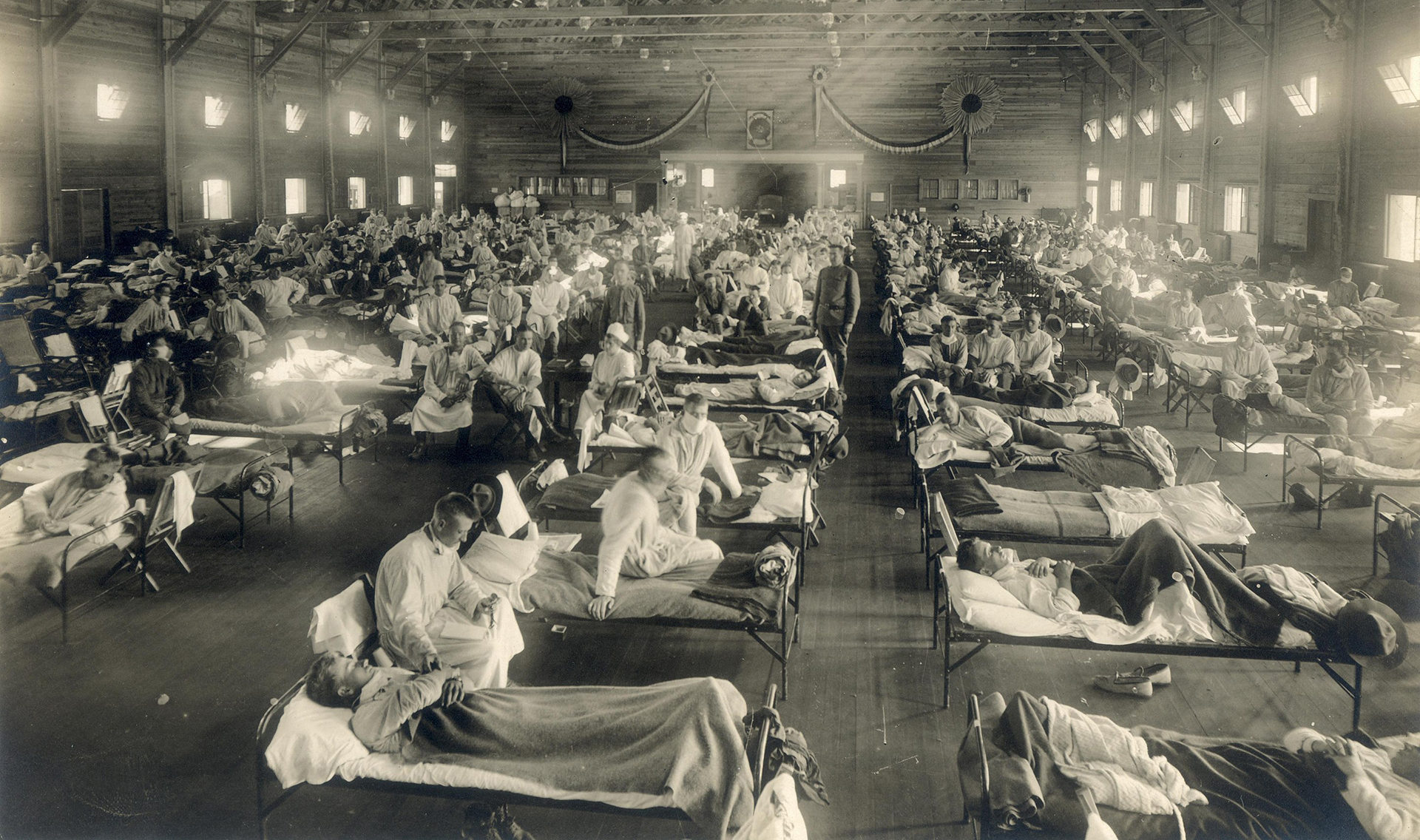

This is part four of an ongoing series on the H1N1 Influenza A virus that killed 675,000 Americans between 1918 and 1919. We are telling the story, as much as possible, through the words of reporters of the time, from either The New York Times archives or newspapers on the East End, such as The East Hampton Star.

“Give my regards to Broadway,

Remember me to Herald Square.

Tell all the gang at Forty-Second Street

That I will soon be there.

Whisper of how I’m yearning

To mingle with the old time throng

Give my regards to old Broadway

And say that I’ll be there ere long.”

– George M. Cohan-1904

The banner headline on The New York Times on Friday, October 31, 1918 began “Allies Near Decision On Armistice Terms, Giving Definition To Wilson’s Points.” “The War to End Wars,” as H.G. Wells called it, was coming to an end. Germany and Austria, crushed, were about to accept the Allies’ demand for total surrender.

On page 13 of The Times that day, a half column was dedicated to the death of one of the most powerful theater owners in America. “A. Paul Keith, President and half owner of the B.F. Keith Vaudeville Circuit, and President of the United Booking Offices, died at 7 o’clock last night of Spanish influenza at the home of E.M. Robinson, a business associate, at 200 West Fifty-eighth Street.”

Three weeks before Keith’s death, The Times had begun running a daily chart, much like a scoreboard, in order to keep track of the new cases and deaths attributed to what is now classified as the H1N1 influenza A virus, each day in the city. The pandemic spanned two years, 1918 and 1919. On October 31, 1918, there were 5349 new cases reported, with 671 deaths. The total number of cases was a spike, due likely to a backlog of unreported cases, Dr. Royal Copeland told The Times. The number of deaths, however, indicated a downward trend.

Copeland was New York City’s Health Commissioner. He had the power to shut down the city’s schools, theaters, and businesses, to battle the pandemic. It was a power he never invoked.

A little more than a month earlier, on September 28, on page 10, The Times reported 27 deaths in the city from either influenza or the fatal pneumonia the virus frequently brought about. On that day, Copeland was quoted as saying, “We have no intention of closing the schools and theaters, as I believe that the children are better protected in the schools than they would be in the streets.” Two days later, he proclaimed in The Times that the worst of the viral outbreak was over.

On October 5, there were 1695 new cases reported of influenza.

Instead of shutting the city down, The Times reported on October 5, Copeland took a different approach: “In order to prevent the complete shutdown of industry and amusement in this city to check the spread of Spanish influenza, Health Commissioner Copeland, by proclamation, yesterday ordered a change in the hours for opening stores, theatres, and other places of business.” By staggering start times across the city, Copeland reasoned, the density of rush hour crowds on the city’s subways, El trains, and trolleys would be decreased, slowing the spread of the disease. He also ordered all stores in the city to close each day at 4 PM, except for pharmacies and stores selling food.

As the numbers of infections and deaths from the H1N1 influenza A virus began peaking in the city in October 1918, it also was rapidly spreading on the East End of Long Island.

The East Hampton Star, a weekly newspaper, came out every Friday in 1918. The October 4 issue of The Star reported six cases of influenza in East Hampton, along with eight more in Sag Harbor, where there also was one death from the disease. One week later, there were 35 cases in East Hampton. On October 18, that number had almost quadrupled to 125. Unlike New York City, East Hampton, along with the other towns and villages across the East End, closed its schools in reaction to the pandemic. Sunday schools were cancelled, as were most public gatherings, The Star reported.

The Star also reported on numerous visitors from points west staying on the East End with friends or family in reaction to the epidemic.

While The Times chronicled the deaths from the disease of persons of note, The East Hampton Star, being a local newspaper, gave a look at how devastating the 1918 influenza virus was on the local level. On October 11, The Star reported, “Mrs. Chas. Coates, who has been suffering with an attack of this disease, was found dead in her bed. Later on in the morning, son Edward, age sixteen, died of the same disease.”

In Washington, President Woodrow Wilson remained silent. Historian Michael Beschloss, author of nine books on the presidency, said last month on MSNBC that Wilson misled the American people about the pandemic because he did not want to undermine the war effort by lowering morale at home.

The administration operating underneath Wilson, however, was not silent. Instead, through news reports, it actively misled the American people about the cause and danger of the highly contagious disease.

On September 19, on page 11 of The Times, a headline proclaimed: “THINK INFLUENZA CAME IN U-BOAT,” with a sub-headline that read: “Federal Health Authorities See Possibility of Men from Submarine Spreading Germs.”

“WASHINGTON, Sept. 18. — That the outbreaks of Spanish influenza, which have given army official some concern, may have been started by German agents who were put ashore from a submarine, was the belief expressed today by Lieut. Col. Phillip S. Doane, head of the Health and Sanitation Section of the Emergency Fleet Corporation,” The Times read.

Right idea, but wrong war. It wasn’t until June 1942, during World War II, four German saboteurs, armed with explosives, were put ashore, via submarine, in Amagansett. The four were soon captured, but not before taking the 6:59 AM Long Island Railroad train to Manhattan. At about the same time, another German submarine dropped four more saboteurs off at Ponte Vedra Beach, near Jacksonville, FL. They, too, were quickly captured. Six of the eight spies were executed.

October 31, 1918, the day The Times reported on the death of A. Paul Keith, concluded the darkest month New York City had ever seen. Over 16,000 residents had died from the disease.

A few days earlier, Queens Borough President Maurice Connolly had implored Mayor John Francis Hylan to send workers to Queens, where 60 percent of the city’s cemeteries were located, to help bury the 2000 bodies that had accumulated.

First responders, such as police officers, experienced a high death rate.

The city suddenly had a growing population of orphans it had to deal with.

Doctors and nurses had been diverted away to serve the war effort. Trained nurses in particular were in short supply. They worked in 12-hour shifts.

On October 14, on page 17, The Times documented the death of one of those nurses. “Her Influenza Work Fatal,” the headline read.

“Miss Mary A. McCusker, Superintendent of Fordham Hospital, died yesterday of pneumonia following an attack of Spanish Influenza. The hospital is crowded with patients and short-handed for nursing help. Miss McCusker had worked night and day until a week ago, when she herself was stricken by the disease. Miss McCusker was 28 years old.”

Next week: The war is over, but the virus continues to kill: the third wave.

This is part of a series on the influenza 1918 pandemic. Click here to read last week’s piece.