1989: How Trump Helicopters to the Hamptons Led to a New Airport Terminal

On Friday, May 28, 1989, a shiny black Sikorsky helicopter with the word TRUMP in giant silver letters on the side slowly descended down to the East Hampton Airport and settled down on the tarmac just a few hundred feet from the terminal. A door opened and a stunningly beautiful blond stewardess in a Trump Air uniform came down the three steps. She stood to one side and smiled cheerfully as the 10 wealthy and well-dressed passengers climbed down after her to head toward the terminal.

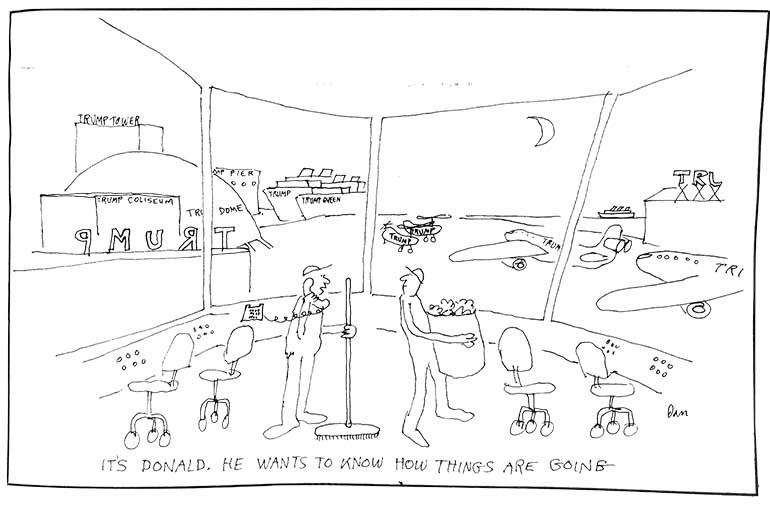

Donald Trump had told the media about his new service. His helicopters had been used earlier to ferry people back and forth from New York City to Atlantic City and were painted a garish green and orange. He had repainted them a classy black and silver. “The helicopters are the same model used by the President of the United States,” he said. He was referring to President George H. W. Bush.

These passengers were the first ever to land at East Hampton as a scheduled helicopter service. They walked—the women in dresses and high heels, the men in suits, ties and dress shoes—to be greeted in front of the terminal by friends or family eager to see them and help them with their luggage.

This was not a proper airport terminal. It was a broken-down little shack. Paint was peeling on the front door. A window was broken. The roof leaked. Inside was a tiny waiting room where a single ceiling bulb shined down on a cigarette machine, a Coke machine, moldy walls, sagging floors, ripped “couches” that had earlier been back seats of automobiles and an earthy foul smell of sweat, cigarettes, rats and bad plumbing. A small 3×5-foot bathroom had been attached in one corner when it was decided in the 1930s that there ought to be something more than an outhouse for the visitors. But the door didn’t close properly.

If the terminal was a disaster, it did have its history. After Charles Lindbergh flew from Long Island to Paris in 1927, young American men everywhere also wanted to be fliers, and many towns created little airstrips to accommodate them. Here, locals mowed a grassy runway with a tall metal pole topped by a windsock at one end. On the other end, the following year, a local farmer who had an old World War I Army barracks he’d bought from Camp Upton in Brookhaven and used to house farm workers towed it to the new airport to be the new terminal. A few years later, another farmer hauled over a chicken coop to attach to the barracks to give the terminal a little more room.

A few years after that, some of the farmers noticed that other airports were building control towers. So they built one here and attached that to the terminal. It was made of wood, 30 feet high with a staircase inside up to a space with windows all around. But because there was no heat and the windows did not open, this tower was freezing in winter and broiling in summer. It was still there, abandoned, when the first of those elegant passengers emerged from the Trump helicopter in 1989.

In the 1980s, the Hamptons was much different than today. There were oceanfront enclaves of mansions for the wealthy summer people, but they numbered just a few hundred and their occupants kept exclusively to themselves for the short summer season. The only other large group of summer people were the tourists, who’d come on weekends. There was also a small smattering of intellectuals from the city—actors, writers, artists, sculptors and the like, living in cottages in the woods. Many shared the long, cold winters with the locals.

But times were changing.

In 1989, besides the Trump helicopters, two rival no-nonsense airlines with twin-engine Beechcrafts also began flying regular daily service between East Hampton and New York. So Trump’s high-fashion choppers were just the icing on the cake. (They were followed after that first week by the appearance of Trump’s 282-foot yacht, Trump Princess, anchored just offshore. It couldn’t dock, though, because there was no slip with enough draft to accommodate it.) All of this and more certainly shined a spotlight on our disgraceful airline terminal. Something had to be done.

Thus was born Beaux Arch ’89, an international competition spearheaded by local architectural critic Alistair Gordon. Architects everywhere were invited to a competition. The winning design would be the new East Hampton Airport terminal.

The competition electrified the architectural community. Some of the world’s greatest architects, from Morocco, Spain, France, Italy, Mexico, Japan and dozens of other countries, submitted elaborately built models to go with their plans and elevations. Some entries looked like airplane wings, others like giant propellers, still others like glass boxes. One of these would make East Hampton Airport famous. And, it was said, the career of a winning young architect would be assured, or, if a famous architect won, it would be another feather in a cap.

For a month, the models built by the 200 entrants were displayed on adjacent tables in the large LTV television studio on Industrial Road in Wainscott. The townspeople, and the judges, came to look them over.

Some were appalled with what they saw. This was to be a new gateway to the Hamptons. Other gateways were our lovely train stations, beautifully restored 19th century affairs built in half-timber, shingle or Victorian style. When looked at from that perspective, these new entries were outrageous. Others felt having such a building would put the Hamptons on the map as a new world-class resort destination, like Palm Beach, the Riviera, Palm Springs or Aspen.

The winner of the competition was a boxy modern affair designed in a Moroccan fashion with high louvered windows to provide ventilation on days of high temperatures as might happen in Casablanca.

But before the awards ceremony, many local residents expressed their displeasure in all the local newspapers, particularly in Dan’s Papers. Something in keeping with our old New England heritage would make more sense, they wrote. I agreed. I suggested we build a terminal with a central rotunda reminiscent of a merry-go-round. An airport terminal with that design had already been built on Martha’s Vineyard.

Other newspapers, notably The East Hampton Star, favored going with the winner. The Moroccan entry had won fair and square. And if this building were not built, then surely the art world would never again favor East Hampton with a design competition.

To determine what to do, Town Supervisor Tony Bullock ordered a town-wide referendum. Prior to the vote, he ordered the model of the winning entry placed in the window of the East Hampton Village hardware store on Newtown Lane for a month for everyone to see.

The townspeople voted against the Moroccon entry by a margin of two to one. And the winning entry was

never built.

The architectural firm that won sued. And the matter remained in court for more than five years, during which time the old terminal sagged and smelled worse and worse. Then, eight years after Beaux Arch ’89, the old terminal was bulldozed down—it took an hour—and the new terminal, designed by Robert Lund Associates, a local Southampton architectural firm, was opened for business in its place.

It is there today. The main waiting room features a grand upper-floor rotunda whose interior wall is a canvas for a local artist’s mural. It is similar to the WPA mural inside the Marine Terminal at LaGuardia Airport built in the 1940s for international travelers crossing the Atlantic in Pan Am seaplanes.

I never traveled to New York aboard a Trump helicopter. But I sometimes flew to LaGuardia Airport aboard one of the twin-engine Beechcrafts from the rival airlines. On one of those trips into the city, an extraordinary thing happened onboard.

In the plane were a pilot and co-pilot up front, and behind them a total of 12 passengers sitting in two rows of six with an aisle in between. It was a beautiful afternoon above New York. The spires and needles of all the skyscrapers below were a breathtaking sight to see as the plane banked in wide circles, waiting for LaGuardia traffic control permission to land.

From behind me, I heard the click of a seatbelt, and then I saw this large woman stride up the aisle to the backs of the two pilots.

“Excuse me,” she said loudly. She tapped one of them, the pilot, on his shoulder. He turned. He was wearing bulky earphones.

“Please sit down, miss,” he said.

“We have to land,” she said. “I have a very important meeting I must attend this afternoon.” She showed the pilot her watch. A Rolex, I suspected.

I was quite horrified.

“It will take as long as it takes,” the pilot said. “Sit down.”

The woman let out a long hiss. Then she wheeled around, stomped back to her seat and sat. I did not hear a click.

“We’ll see about this,” she shouted up to them. We all huddled in our seats. But that was the end of it.