Lindberg Unearths ‘Scandal On Plum Island’

Plum Island has always had an air of mystery about it. The beautiful spit of land off Orient Point is home to the controversial Animal Disease Center. It was also used as a bargaining chip by Clarice Starling in Thomas Harris’s “The Silence of the Lambs.” Nelson DeMille used the location for his eponymous book in the mid-’90s.

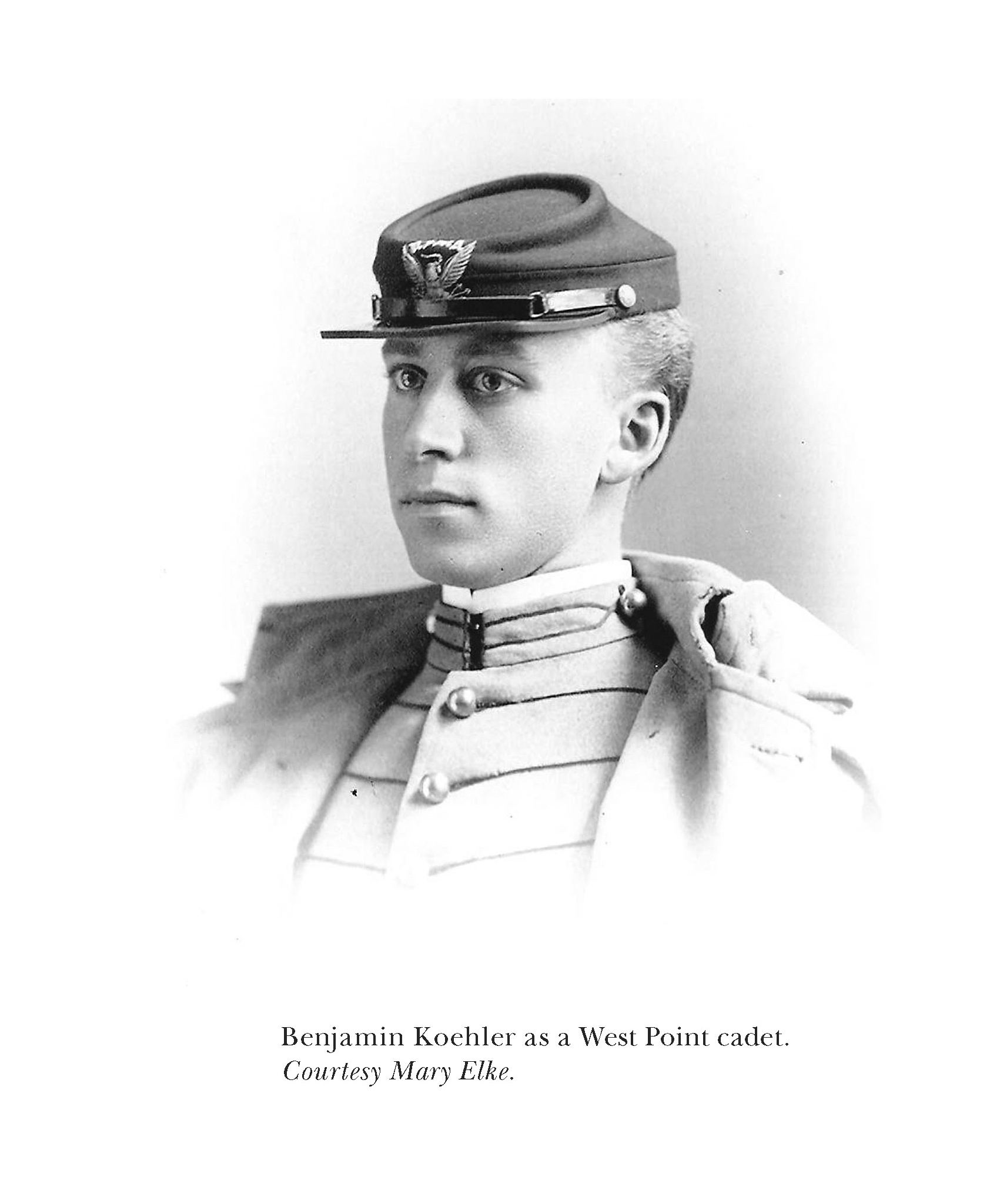

But there is an even deeper, darker story buried on the island, which has only recently been unearthed by author, journalist, and lawyer Marian Lindberg of Wainscott — the birth of homophobia in the U.S. military. Her newly-released book, “Scandal On Plum Island: A Commander Becomes The Accused” (East End Press), details the 1914 trial and ultimate discharge for “immoral conduct” and “homo-sexualism” of a distinguished Army Commander, Benjamin Koehler, stationed at the island’s military base.

“The captain wore a see-through dress. No dispute about that. Even the captain admitted that in a certain light, guests at the party could see the outline of his body through the muslin shift. Months later, a lawyer would press for details: Was the dress tied at the waist? What color and length were the captain’s socks? Did others treat him ‘as if you were a woman’?”

This kicks off Lindberg’s book, which includes colorful characters of the day, along with a detailed portrait of Koehler and his trial, and the military history of Fort Terry on Plum Island.

A talk with Marian Lindberg this week revealed how this story came into her life.

How did you end up going down this particular rabbit hole and at what point did you realize, “There’s a book here,” rather than an article or series of articles?

Since 2005, I have been on the staff of The Nature Conservancy, based in East Hampton, mostly working on land preservation deals. Helping to preserve Plum Island after the Plum Island Animal Disease Laboratory moves to Kansas in 2023 is one of my assignments. It was in that context that my then-colleague handed me a copy of “A World Unto Itself: The Remarkable History of Plum Island” in January 2016.

I took the book home and read much of it that night. The chapter about Major Koehler, written by Amy Kasuga Folk, intrigued me immediately. The journalist in me wondered why I had never heard of such a significant, early case in LGBTQ history that had happened nearby. The lawyer in me wondered about the legal details of the case, as Amy, a historian, came out on the side of Koehler’s innocence but had not analyzed the case from a lawyer’s perspective. And the feminist in me was struck by a case in which 16 male accusers were said to have lied.

This was the year before #MeToo became a force, but there was plenty of sexual misconduct being written about and I have long been interested in sexual harassment and sexual abuse issues. I thought it was interesting that here, in 1913-14, 16 men were accused of being untruthful when reporting allegations of sexual groping by Ben Koehler.

So, several cylinders were firing. I thought from the start that Koehler’s story merited a book. I called Amy (nervously, as we were strangers) and asked whether she planned to do anything more with the material. She said, “Like what”? I said, “Like a book.” She said she might like to but doubted she would have time in the near future to pursue it, so she said I should go for it.

I’m grateful to Amy. She shared some documents and photos with me, read a draft, and has been a great ally in getting this story of injustice fully investigated and told. The more I started researching, the more I was hooked, especially after I spoke to Koehler’s grand-niece (she lives in California) and learned that the story had cast a shadow over the family, yet they knew few of the details.

One has only to be familiar with Oscar Wilde, and other persecuted homosexuals of that time, to know that homosexuality was frowned upon, if not illegal. What about Koehler’s story did you find particularly egregious or shocking?

Actually, attitudes toward homosexuality are much more complicated. For example, close male friends held hands in the 1800s and this was not stigmatized. Wilde was convicted of sodomy. There was no allegation that Ben Koehler engaged in sodomy — the allegations concerned groping — so anti-sodomy laws did not apply. There was no law banning homosexuality per se at the time.

The federal government did not begin taking action against perceived homosexuals as a class until 1909. The Immigration Bureau was the first federal agency to do so. I can’t say for a fact that the 1914 case of Ben Koehler was the first domestic prosecution of a senior military officer for alleged homoerotic acts, but I am not aware of an earlier one.

Part of what made the story fascinating to me is the emergence of the hyper-aggressive standards of masculinity after the Spanish-American War (1898). In part, men’s policing of other men’s sexuality arose as a result of denigrating the feminine — in women, and in themselves — and this, in turn, arose as pushback to women’s greater participation in public life in the 1890s and a sense by some, such as Theodore Roosevelt, that American men were becoming too soft in the 1890s for their own and the nation’s good.

The changing standards of manliness in the 1890-1920 period are not only interesting, but relevant to the coded concerns with “manliness” (and glorification of strength defined as physical power and dominance) that still exist in our politics and social life.

I found many aspects of the case egregious. There was terrible abuse of power by a senior official in D.C., and I was able to document the creation of fake evidence. The claims were fantastic on their face. The “double life” theory was carried to an unbelievable extreme based on innuendo and speculation as to how “male degenerates” would behave.

I grew enormously as a person both in self-knowledge and in compassion for people as different as an army officer born in the 19th Century and present members of the trans community. Our current ideas of gender norms are socially constructed to the disadvantage of fully human men, women, relationships, and society. I also saw the lesser-known sides of a number of famous people, both good and bad, from Roosevelt to Susan B. Anthony (related by marriage to the Koehler family). Going back in time and seeing well-known people and events from unconventional angles was fun.

Did you ever feel, while you were writing, that Benjamin Koehler’s spirit was with you? Maybe that he felt exonerated?

Who among us has never felt misunderstood or misperceived? That is a way in which all of us can relate to Ben Koehler. I related to him in addition because of some similar traits. I also felt part of his purpose in my life was to help me understand military people better, including my father, who was a captain in WWII but started out as an enlisted man (which I discovered by requesting his records after his death.)

I liked Ben’s independent, educated sister who lived with him on Plum Island and whose letters, given to me by her granddaughter, made a big difference in my understanding of the case and of Ben. Who knows, there may be an official request for a pardon in the offing. One reader did say it was too bad Ben didn’t have me as his lawyer!

What do you hope to accomplish with this book? Is there anything besides telling a good story?

I’ve written it as a fast-moving story. Nelson DeMille said it reads like a legal thriller. My aim was to reach a broad audience (though there are 50 pages of end notes for people who like a more scholarly approach). Readers are free to reach their own conclusions, but I hope the book leads to greater tolerance of people who seem different — for whatever reason. The book shows the harm that can come from stereotyping based on superficial features.

Also, as it is Pride Month, my book can also be seen as an offering of allyship to the LGBTQ community.

“Scandal on Plum Island” can be found at www.eastendpress.co, at local bookstores, and online. Lindberg will join Canio’s Books via Zoom on Friday, June 19, at 6 PM. Log onto www.caniosbooks.com for the link.