Shelter Island Protest Organizer: Take A Deep Look At Yourself

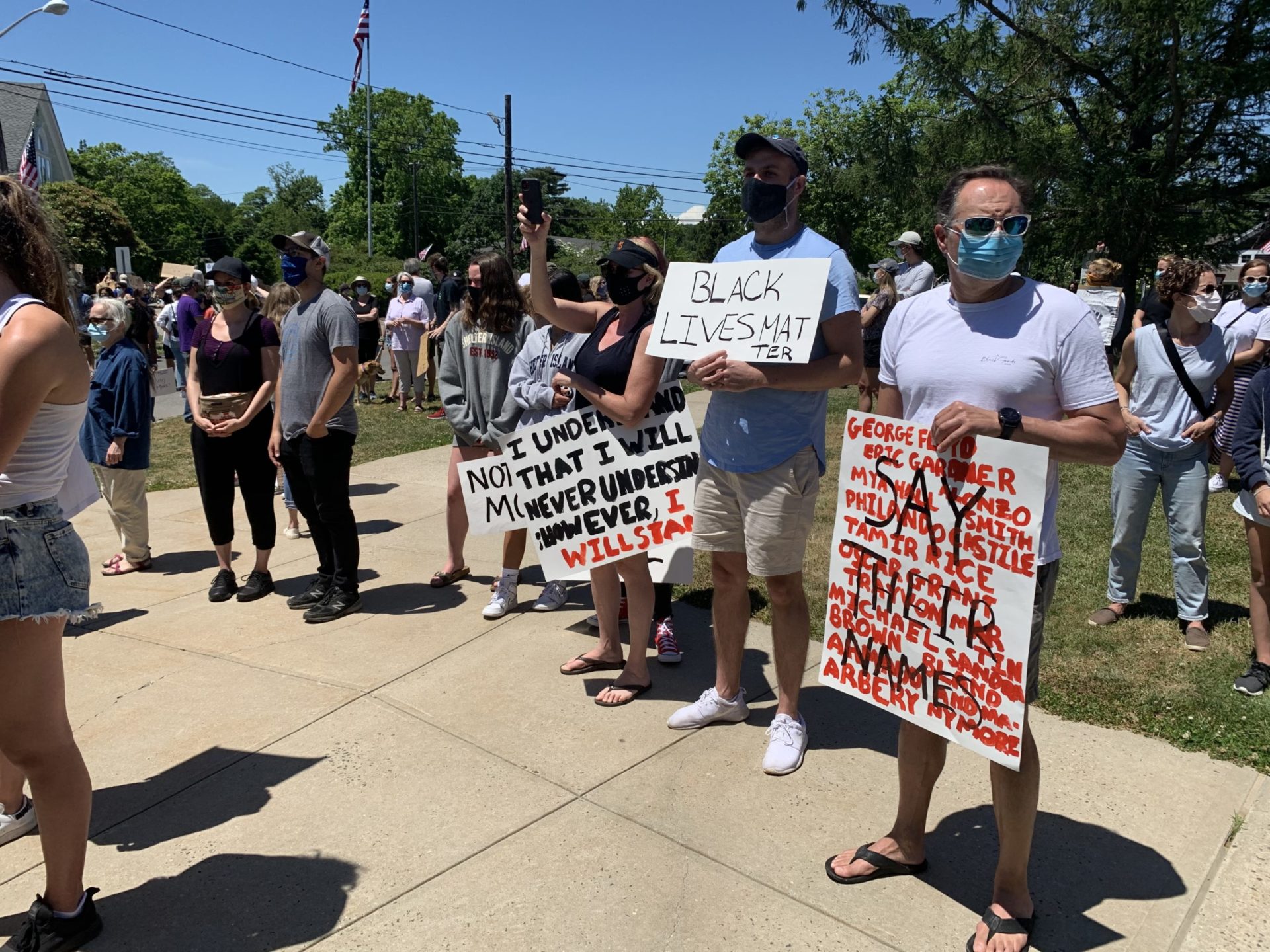

The nationwide protests against racial injustice and police brutality reached the small, mostly white community of Shelter Island, one of the smallest towns on the East End. Some took the ferries from either of the two forks to be there, but many of the approximately 700 people in attendance were full-time or summer residents who wanted to stand with those calling for a change.

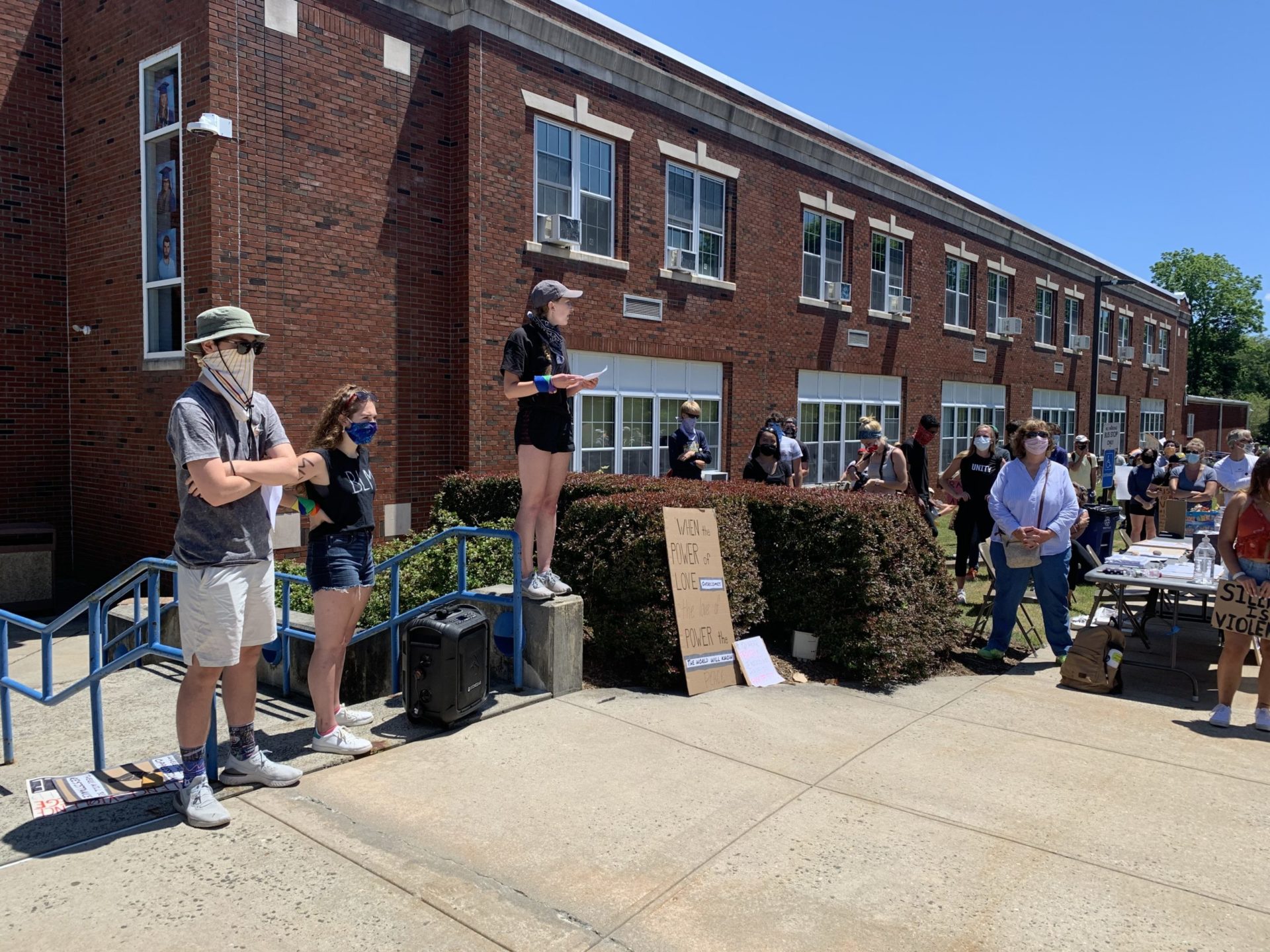

Three high school seniors, Henry Binder, Emma Gallagher, and Abby Kotula, organized the protest in line with the Black Lives Matter movement. “I would also like to acknowledge the lack of diversity. This is no coincidence,” Gallagher said to the crowd that gathered by the Shelter Island School.

“Here on Shelter Island we are lucky enough to have a good police department. But this is not about us. This is about a societal shift to equality,” she said. “If you are here only to blame police officers, I ask you to take a deep look into your life. How many things do you not even realize are offensive? How many privileges do you not even know you have? Do your research. Ask the black people in your life how you can do better. Blaming one group of people is not the answer.”

Gallagher said the protest was call for change to national system, beyond just law enforcement. “And this is a system we have all contributed to at one point or another. If we want change we all have to accept that responsibility. Each and every one of us is the problem. We must call each other out. We must listen when others call us out. We must call ourselves out.”

The trio of organizers led a short march from the school, down North Ferry Road, the main drag on the island, shut down to traffic by police. In front of the Shelter Island police station, they stopped to observe the amount of time George Floyd was held on the ground with a Minneapolis police officer’s knee on his neck — eight minutes and 46 seconds. Some were on the stomachs with their hands behind their back. Others took a knee. Police stood innocuously nearby.

About halfway through, Binder asked the crowd to chant, “I can’t breathe,” for the rest of the time.

When the time had ended, Willie Jenkins, a local activist who has organized and attended many of the protests on the East End in recent weeks, addressed the crowd. Though the 37-year-old grew up in Bridgehampton only a few miles from the South Ferry, he said he only knew one person of color from Shelter Island his whole life. “This is filling my heart right now,” he said of the large group.

While people may be used to seeing acts of injustice happening elsewhere thanks to television news coverage or social media, Jenkins told them discrimination happens a lot closer to home than they realize. He grew up in what was then a predominantly black neighborhood. “But please believe, we are surrounded by white people, excuse my terminology. And the police department was mostly white,” he said.

“I didn’t know it was not normal not to get pulled out of your car growing up. I thought it was part of procedure. I thought getting searched was just what happened. Would you guys believe me if I told you that right in Bridgehampton a police officer pulled into my yard? I was just standing in my yard. He pulled into my yard, he pulled a gun on me, told me to empty my pockets. I asked him why? His reasoning was I was in a drug area . . . I said, ‘Officer, I live here.’ He said, ‘It doesn’t matter.'”

During some of the protests over the past two weeks, Jenkins said he lost his voice from chanting. People have been calling out injustices for centuries, he said. “We have been screaming and screaming and things are not right. I see a difference today. I see I’m not screaming by myself. You guys are lending me your voices.”

The crowd began to shout, “Black lives matter. Black lives matter.”

“But just remember while you guys can go home, you might be able to forget about this. Tomorrow, I’m still going to be black. The few African Americans that you do have on Shelter Island are still going to be black. I want you to talk to them. Ask them what they have been through,” Jenkins said. “You’ll be surprised. Because when you’ve not been heard for so long you have a tendency just to shut up and just deal with it. You can see the country is sick of dealing with it.”

Looking around at the mainly white crowd, Jenkins said: “You guys don’t even know how much this makes a difference. Never in a million years would have thought you guys would do this.”

One man yelled out: “We have your back.”

“If I didn’t consider myself such a tough guy, I’d cry right now.”

After a short march back to the school, protestors again gathered to hear speakers. Aterahme Lawrence, a 2014 Shelter Island High School graduate known as Meme, spoke frankly about “racist, discriminatory behavior” she and her family experienced.

“There was a point in my life where I felt like my peers, the police, and the faculty in the school had left me down,” she said.

“It wasn’t the comments about blacks, fried chicken, or watermelon or Kool-Aid. It wasn’t them rapping the N-word or calling me one straight to my face. It wasn’t even the times that I was choked or spit on. It was just more general statements about black people being poor and how most of them were on welfare,” she said. “It was general statements that black people were truly bad people when I was one standing right before them.”

While she tried to speak up in the past, she was shut down and told she was the aggressor, causing the problem. “I’m not saying that my time here I was completely innocent but I’m also saying that a lot of the issues that I did face stem to one true issue that I was the only black person in my class. That my family were some of the only black people.”

She did not want apologies or for people to feel bad for her. Instead, she asked the crowd to speak to their children and to educate themselves.