Jaws: Before the Movie

The movie Jaws, released in 1975, is considered one of the greatest films of all time. Receiving its world premiere at the East Hampton Cinema, it launched a young Steven Spielberg onto his spectacular film making career. It also transformed the Hamptons. By the following year, Steven Spielberg and Roy Scheider and others from the film had taken up residence in the Hamptons. Soon, other movie stars followed. From Jaws forward, the Hamptons grew from a group of small beachfront summer villages into the glittering home of the rich and famous it is today.

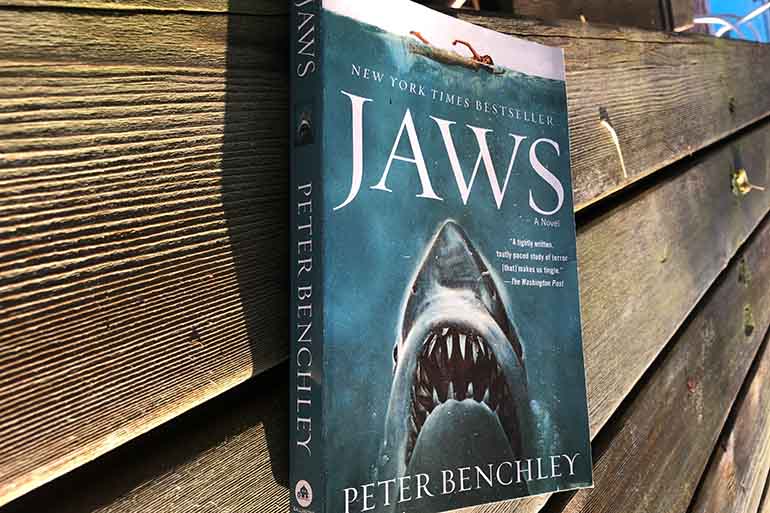

Why had this so transformed us? The movie was adapted from a book called Jaws, written by Peter Benchley two years earlier, which was set in the Hamptons. It sold more than 9 million copies, was a New York Times Best Seller. Its success captured the attention of Universal Pictures. They made a deal with Benchley, hired Spielberg and produced the film.

Although critics have written about the Hamptons connection in the book, I never did read it. Last week, 45 years later, I did.

In Benchley’s book, the action takes place in the fictional beachfront village of Amity, located on the ocean halfway between East Hampton and Bridgehampton. You get to it, he writes, by turning south off the Montauk Highway and driving down to the beach. So it would be beachfront at or near Sagaponack.

Amity has a mayor and a police chief. It has a marina, a row of stores and restaurants, a public beach, a lighthouse and its own newspaper run by a young man named Meadows. Its economy is built on summer tourism. And if no summer tourists come because, ahem, there is a killer shark eating tourists offshore, other tourists will go to East Hampton or elsewhere. Thus the residents of Amity (Amity Island in the film) will have to go on welfare and food stamps for the winter.

This cannot be allowed to happen.

And so, in both book and movie, when a huge killer shark starts feasting on the tourists splashing happily in the ocean just before the Fourth of July, it’s got to be kept secret.

The first person to get eaten is a beautiful young teenage girl. It’s the same in both book and movie. In both, the mayor begs the Police Chief (played by Roy Scheider) not to close the beaches to swimming. It will ruin the economy. The two argue. It’s decided to continue to allow swimming. When three more people get killed—in both the movie and the book—the mayor gives in. Swimming is prohibited and the police enforce it.

Also in both book and movie, it’s decided to hire this crazy shark fisherman named Quint to kill the shark. He’s a character in the book who Benchley later said was modeled after Frank Mundus, a real killer of 3,000-pound sharks who fished from Montauk for many years.

From here, the screenwriters for the film simplify what Benchley wrote and the plot of the book and movie diverge, some in small ways but in other ways large. Quint in the book, for example, has a dock in the bay down at the end of Cranberry Hole Road in Amagansett’s Lazy Point and the mayor and the police chief drive out to hire him. In the movie, he docks his boat at Amity.

An expert from Woods Hole, Massachusetts arrives on the scene, by invitation in the book and in the movie by just showing up because he’s heard about the shark. This expert, Hooper, played by a young Richard Dreyfuss in the movie, meets not only Police Chief Brody but also Brody’s wife, Ellen. In both book and movie, he’s staying at a hotel in Amity, and so, in both, the Brodys invite him for a home-cooked dinner. In the book, Ellen is unhappy in her marriage. She smiles alluringly at Hooper, touches his sleeve when he talks at dinner, and, after Brody goes out on a call, makes a date with Hooper to come up to his hotel room, which she does. The torrid affair is described. In the movie, there is the same dinner, but Ellen keeps touching the sleeve of her husband as he talks. She’s mad for him. And she hardly notices Hooper.

Though in the movie the mayor’s only concern is the town losing its summer season, in the book, it’s complicated. He is presented not only as the mayor but also as a wealthy summer resort developer who has fallen in with a bunch of New Jersey mafia types now demanding huge amounts of money. If Amity is a ghost town, he could be killed. And nobody in town but us readers knows about this little wrinkle. (Midway through the book, though, Mayor Vaughn tearfully tells Brody’s wife, a good friend, that he’s running away to points unknown, having failed his family, the town and now the mafia.)

Also in this part of the book, Ellen realizes what a fool she’s been and so decides she really loves Brody and the two children. Too bad for Hooper.

Finally, we go off to the three guys in a boat chasing the killer shark in the sea. It’s the same in the book and movie. But the story line differs.

In the book, Brody tries picking a fight with Hooper, suspecting he’s having that affair with his wife. But Quint gets between them and scolds them and tells them to pay attention to the job at hand.

In the movie, Hooper and Brody are close buddies, and in a famous scene reportedly put in ad-lib, Hooper and Quint sit in the ship’s cabin drinking late into the night, showing each other the scars they have on their bodies from previous shark encounters. (“That’s nothing. Look at THIS.”)

Soon enough the shark appears and the battle begins. And again, the screenwriters have changed things. In the book, two men die before the shark is killed. In the movie, it’s just one.

SPOILER ALERT. Quint in the book gets his leg tangled in a rope after harpooning the big fish and is dragged overboard to his death. In the movie, Quint is on the pulpit, aiming another harpoon at the killer, when the front end of the big fish crashes onto the deck, opens its great jaws and chomps Quint to death (lots of blood.)

In both the movie and the book, Hooper is lowered over the side of the boat in a shark cage so he can make an underwater film of the shark. The shark sees him, attacks and bends the metal bars to try to nibble at him. Hooper, horrified, drops his camera.

SPOILER ALERT 2. In the book, the fish grabs Hooper and eats him. Chomp. End of Hooper. That’s what you get for sleeping with the Police chief’s wife. But in the movie, where no such transgression has taken place, Hooper in his scuba gear manages to struggle away to hide behind underwater rocks on the sea floor.

And so we come to the climax, where Brody goes one-on-one with the shark.

SPOILER ALERT 3. In the book, the ending lacks drama. The wounded shark corners Brody on the ship’s bridge as it begins to really sink—and yes, it entirely sinks—but then at the last minute, with Brody helpless, the shark loses consciousness because of his wounds, slides backwards across the deck and sinks bloodily to the bottom of the sea. Brody, in a life jacket, swims for shore.

In the movie, the shark cannot be stopped. Intent on chomping Brody, the shark corners him, opens his mouth wide, and in that moment Brody picks up a rifle and shoots at the shark. The bullet goes wide, but punctures a big compressed air tank in the shark’s mouth. The tank explodes. Kaboom. Bloody pieces of shark fall everywhere.

And then, wouldn’t you know it, Hooper comes out from behind his underwater rock, swims to Brody and the two hug, high five, laugh and then paddle a makeshift raft toward the sunset over the lighthouse on the shore not far away.

The End.

I liked the movie better. Clear, direct, uncluttered and with long, terrifying moments when the shark eats somebody.

But because the filmmakers thought the Hamptons too busy to have an Amity, they made it Amity Island, and filmed the movie entirely on Martha’s Vineyard, isolated, alone

and terrible.

In the book’s introduction, Benchley tells the reader he became fascinated with killer sharks at the age of six. As a teenager, he always carried with him a newspaper clipping reporting the capture of a 4,330-pound great white shark off Long Island 10 years earlier. In his 20s, he’d take it out and show it to prospective publishers about the book he wanted to write.

I wrote about and photographed that monster in this newspaper in 1964. It was the second of three big monsters that Mundus caught off Montauk during his time. The others were in 1958 and in 1986. (That one in 1986 holds the world’s record for the biggest fish ever caught on rod and reel.) I remember all three well. You do not forget the sight of a 16-foot-long killer fish lying dead on Gosman’s Dock. You stare at blank, unseeing grey eyes. Touch the cold flesh and sandpaper skin. The mouth propped open to show the rows and rows of dagger-size teeth. The bloody snout. The giant tongue, hanging out to the side.

And Mundus there to answer questions.

There is an outdoor screening of Jaws on September 4 at Southampton Arts Center, presented with Hamptons International Film Festival.