The Fate of Stargazer Uncertain Once More

The skeleton is almost laid bare, a daunting site here where many will tell you that the real trip to the East End begins.

At the southern point of Route 111 in Manorville, a quarter-mile north of Sunrise Highway, the red giant rises 50 feet toward the heavens. Stargazer. The deer looking skyward, an antler in its mouth, has for some three decades now welcomed multiple generations of Hamptons-bound travelers and then bid them farewell on their return journeys to points north and west. It is as much a part of the local fabric as the Montauk Lighthouse and the centuries-old windmills that dot the landscape.

Over the years, this creation of artist Linda Scott, who died in 2015, has weathered assaults by vandals and nature alike, but the surprise late-August storm that knocked out power across Long Island inflicted some of the worst damage Stargazer has endured in years. It is enough to pose a chilling question: Can it recover this time?

There is an indisputable danger to pulling off the road here, but parking on the side, stepping out of the car and standing in Stargazer’s shadow, the smell of grass rising from the farm on whose earth the sculpture stands, is the best way to embrace the power of this piece. Truth be told, there may be a greater danger in not taking even the briefest of time to feel its strength and its vulnerability.

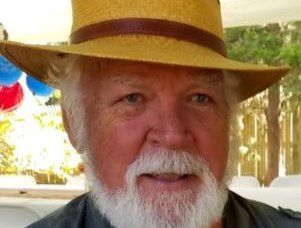

And, in turn, the passion of those who love it, most notably David Morris, Scott’s partner and the engineer who helped build Stargazer in 1991, who has taken on the task of preserving both the physical structure and its legacy through fundraising efforts and hands-on work. Back in 2017, with the help of such donors as Taylor Plimpton, Barbara Slifka and Ben Black and Jarred Kessler of EasyKnock, and the efforts of the Arete Living Arts Foundation to help set up a nonprofit status, Morris raised enough money for the Stargazer Restoration Project to make repairs and give a ray of optimism as the summer season began. At the time, he noted that a full overhaul was ultimately necessary, from the frame to the siding to a new waterproof acrylic stucco coating. Today, he finds himself and Stargazer at a crossroads.

“I don’t know really what to do, which direction to go,” Morris admits. “I’d like to fix it, but I have a year-to-year lease. The property owners never charged me for the property until a couple of years ago, and it’s a year-to-year lease. I don’t know how to raise money on a year-to-year lease. I just had a discussion last week and they said they would talk about it, and I haven’t heard from them.

“I am really reluctant to go and raise money,” he continues. “It’s going to take about $100,000 to re-do the whole thing—and the whole thing needs to be done, but I can’t do it on a year-to-year lease. I want them to guarantee me at least 40 or 50 years if I’m going to build it, because I have to go and get the general public’s money. If I go and fix it and I have a year-to-year lease, and they want to sell the property, we’d be in a mess.”

Morris says the steel fabricator who has worked with him on the sculpture noted that the Town of Brookhaven “owns some property opposite, on the other side of the highway. He said you basically have to rebuild the whole thing anyway, so worst case scenario, if Brookhaven agrees, we could move it across the street, so instead of facing west it would be facing east. That way, the town of Brookhaven would own the property and I could donate it to them and they could keep the upkeep going. So that’s where we are.”

Donations can still be made at LindaScott.org. A sign remains planted in the ground in front of the sculpture denoting EasyKnock’s support from three years ago, and Morris says they “are gung-ho to help me raise money. [They’ve] been there to do it, but I just can’t pull the trigger to go raise money yet until I get the lease. I asked them basically a year ago to make an extended lease, and they said they’d have meetings and talk about it, and it just keeps going on.”

Iconic elements of the East End, what feels timeless and eternal, are also fragile and can be gone in an instant. There are stewards, like Morris, who truly understand their worth, who comprehend the effort it takes to preserve them but also what makes them truly special in the first place, the source of the joy they bring.

Morris can’t help but laugh out loud when he thinks back on the source of Scott’s inspiration. “She loved quantum physics,” he recounts. “This was a stargazer and, she said, a connection of the above and below. She said, it’s really cool, we’re really stardust. She said stars are nothing but hydrogen and helium that it takes a supernova to explode, and that’s when the other elements are made, and finally everything comes down and forms planets and meteors and everything else. And she said the most beautiful part of the whole thing is, it’s made out of energy but it’s conscious energy, otherwise nothing would have consciousness here.”

He laughs again. There’s hope in the sound.

“She just loved looking at the stars and going, ‘We’re stardust. Everything’s stardust.’ This was just a representation of that. Look to the stars. We’re connected to them. We are them.”