Port in a Storm: Tenant Safe Harbor Act Hits Home on East End

They might be your neighbor or somebody next to you in line at the supermarket. Could be that favorite waiter you were so happy to see when his restaurant turned the lights back on, or the owner of that store you were thrilled to shop at when she reopened her doors. You might have seen them in Montauk or Mattituck, Southold or Southampton. It makes no difference. Across the East End, people have needed help throughout the coronavirus crisis, more than you might imagine, and on levels more basic to day-to-day survival than you might know.

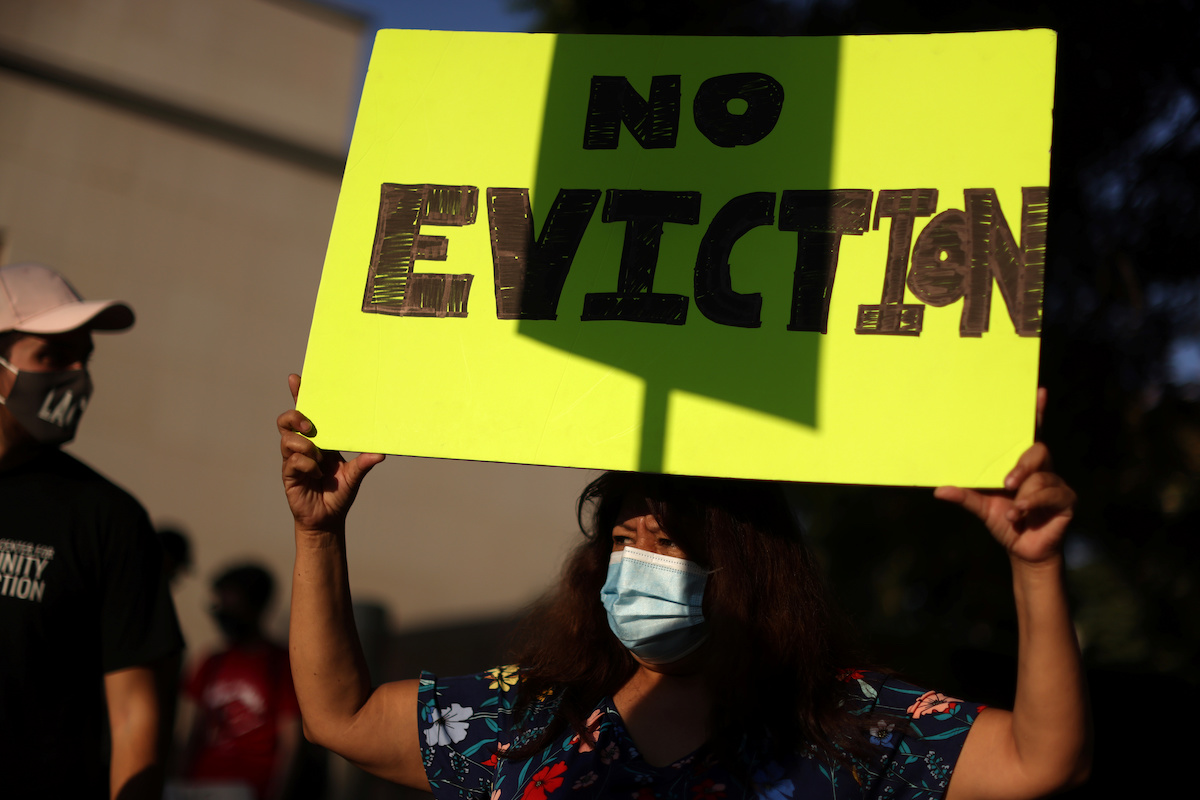

In the beginning of the pandemic, when it became apparent that the economic downturn would quickly put people at risk of being kicked out of their homes for an inability to make the monthly rent, Governor Cuomo issued executive orders to put a moratorium on evictions. That was fine-tuned to give way to the Tenant Safe Harbor Act in June, which assured people would not get evicted during COVID—that is, provided the tenant could show they had incurred economic hardship related to COVID.

The good intent was there. The execution, as with many such efforts, imperfect. And with the positives came the other inevitable.

Back in October, a New York Times story applied a question to the Hamptons. “New York State’s Tenant Safe Harbor Act was intended to help those affected by the pandemic. But what if that harbor is on the fancier side?” In focusing on the story of a young woman who rented a home in Montauk from June 1 to August 8 and, according to court filings, did not pay the second half of her rent, it generated plenty of buzz. The subject was an “influencer” developing “a personal brand” and the rent due was a reported $14,450, so of course it did. According to the Timesstory, she cited the tenant protection law in communications with the homeowners, and was still in the house come September. By mid-October, after legal back-and-forths, she had finally left.

It was not an isolated incident in the Hamptons. A number of other stories came to light over the summer that shined the spotlight on similar situations, raising questions—and in many cases ire—surrounding flaws in the Safe Harbor Act and how it could lead to abuses. Questions like “Can you believe there are all these rich people not paying their rent just because they don’t have to, and now they won’t leave?” Which really weren’t always questions as much as they were judgements, of both certain individuals and the law itself.

In some cases, advantages have been taken, it’s true. That must be remedied. But lost in the kerfuffle of commentary, clever one-liners and social media outrage (some informed, some not) is another truth. That the East End is not made up of only the über wealthy or über wealthy wannabes, but is in fact also home to people who live on tight budgets, some paycheck to paycheck, who work here and raise families here and live in homes and apartments they rent year-round, not only in the summer months. The question is not only what happens when the harbor is on the fancier side, but what happens in the harbor to those who truly, legitimately cannot keep their heads above water?

“When construction was closed down and restaurants were closed down, there were a lot of people who live here on the East End who couldn’t pay their rent,” says New York State Assemblyman Fred Thiele of Sag Harbor. “And having protections for them certainly warranted, and has been a benefit of, this act.

“The intent of the Tenant Safe Harbor Act is a good one,” he continues. “And that is, during COVID—and obviously the numbers again are starting to go up—you didn’t want people evicted out in the streets. And in addition to being difficult for individuals, it’s a public health issue. I think there was good intent, and certainly for year-round rentals—for people where this is their primary residence, and they rent—you want to protect those people.”

And when people who don’t need that protection take it anyway, well, the whole system comes under fire. Especially here on the East End, which offers, as few other places do, an opportunity to assess in close proximity both the need for help and the opportunity to abuse it, perhaps on the very same block.

Now, a key aspect of the Tenant Safe Harbor Act that some people misunderstand is that it does not offer a free pass. “It doesn’t apply automatically and doesn’t stop you from owing money,” notes attorney and East End real estate expert Andrew Lieb of Lieb at Law. “It just prevents eviction.” Even then, a number of parameters exist.

Problem is, it does not prevent people from using the act beyond its intentions. And thus creating, in the minds of some, the belief that everyone is in some way taking advantage—which is, of course, utterly false—and taking the focus off the problem at hand. When you go picking apples at one of our local orchards, a few rotten ones don’t mean the whole bushel needs to be tossed. One renter may have suffered genuine economic hardship, and they now have time to figure things out without having to worry about whether they will have a home. Another renter may have decided they simply don’t want to go back to the city and would rather stay here, even though their seasonal rental is over and economics are not at issue. And thus the justifiable criticism, even from those who believe in the spirit of the Tenant Safe Harbor Act.

For his part, Thiele “didn’t support the bill, because I thought it was over-broad,” he says. “It should apply to primary residence where people live, so they have a roof over their head.

“Where I had a problem with the bill ,” he continues, “was its applicability to seasonal rentals and summer rentals, where people have [another] place to live and they’ve come—whether it’s to the Hamptons or the Catskills or the Adirondacks—and they’ve rented as a vacation home and then have used this statute as a means of either avoiding paying rent or holding over.”

People need somewhere to live. They also need somewhere to make a living. The two are interwoven, a fact that led to a good deal of support in the Hamptons and on the North Fork within the business community from the start of the COVID crisis. Walking down Main Street in any village, driving by empty shopping center and warehouse parking lots during the early days of lockdown, was sobering. Locked doors and darkened windows had many wondering not just when they would reopen, but how they could afford to do so.

“When the shutdown began in the early spring, the majority of commercial landlords were very sympathetic to their tenants, even before the law was enacted,” says Compass real estate agent Hal Zwick, one of the leading experts in commercial real estate on the East End. “Most tenants received either free rent, partial rent or rent abatements for the period they were closed. Once the restaurants and retail were allowed to open in June, some tenants continued to receive partial rent credits to compensate for the reduction in business and therefore profits.

“This was certainly a hardship for the majority of landlords,” Zwick continues, “but some tenants have not paid rent regardless of any deal with their landlords while they have been conducting business. Legal proceedings have begun for many tenants, but they are ‘on hold‘ until January, unless the moratorium is extended.”

The moratorium Zwick references is the current January 1 deadline of Governor Cuomo’s executive order extending, as his office said when he signed it on October 20, “protections already in place for commercial tenants and mortgagors in recognition of the financial toll the pandemic has taken on business owners, including retail establishments and restaurants. The extension of this protection gives commercial tenants and mortgagors additional time to get back on their feet and catch up on rent or their mortgage, or to renegotiate their lease terms to avoid foreclosure moving forward.”

Every business that opens its doors offers a ray of hope. That applies to the East End community at large, the business owner and the property owners for whom charging rent istheir business. The challenge now is how the latter two groups can both be safeguarded while together keeping restaurants, shops and the like moving forward.

“Prospective tenants are requesting COVID clauses in new leases protecting them against paying rent if they cannot be open,” Zwick says. “Landlords, while again sympathetic, are engaging their attorneys to negotiate this point. And landlords and tenants alike are communicating with the insurance companies regarding business and rental income interruption. The insurance industry is reluctant, to date, to add this to policies based on the financial impact that could result. This is an ongoing dialog that is being negotiated on an individual basis.”

And ongoing dialogue is exactly what’s needed. Discussions continue in government regarding ways in which the Tenant Safe Harbor Act could be updated, the language tightened, to better aid the people it was intended to serve. Negotiations continue among tenants and landlords. Debates go on within the East End community as to how to best deal with the inevitable challenges awaiting. We are entering a precarious time, with many new questions to come, and others awaiting answers.

What happens when the harbor is on the fancier side? The waters still rise, and some yachts rise with it, while the vulnerable still fight to stay afloat until the storm passes.