2020: The Year That Was

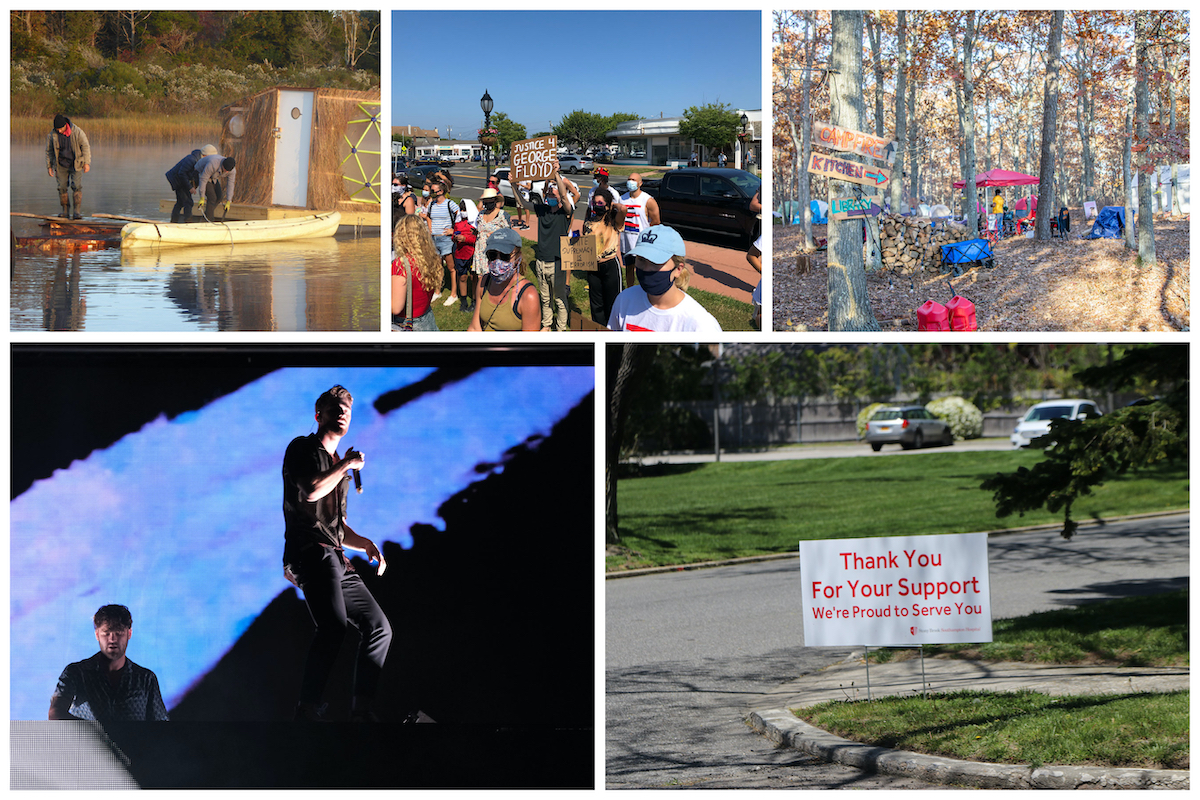

“Unprecedented” is a word that’s been overused to describe 2020, but that doesn’t make it any less accurate. The entire world was forced to think fast when COVID-19 struck. The United States had the most talked-about and important presidential election in recent history. The relationship between citizens and the police faced a reckoning as racial tensions boiled over, amplifying the Black Lives Matter movement. And on the East End, we felt it all. Here are five things that defined the Hamptons and North Fork in 2020.

COVID-19

As a frightening and deadly pandemic raged throughout the world, the Hamptons and North Fork communities mobilized in the face of unprecedented challenges and strife. Stony Brook Southampton Hospital quickly and continuously adapted to the seemingly nonstop changes in guidelines and restrictions to keep patients and visitors safe. Frontline workers, including paramedics, doctors and nurses, risked their lives to care for those touched by the airborne disease. Testing centers opened throughout the East End. Grassroots efforts, such as Brian Tymann’s Help for Local Families, Pietro Bottero and Kevin Leonard’s WHB Local Restaurant Workers Emergency Fund and Duncan Kennedy’s NoFo Community Cares, gave food, money and resources to the needy. BNB Bank was the No. 2 lender in SBA Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) loans. All the while seasonal residents flocked to their second homes and stayed beyond Labor Day to avoid getting infected in New York City, an epicenter of the pandemic.

As 2020 draws to a close, there are still struggles. Numbers continue to fluctuate due to relaxed restrictions and holiday gatherings, and those who refuse to wear masks make it harder for everyone. But there’s hope. Vaccines are being distributed to local hospitals—Peconic Bay Medical Center in Riverhead became the first on the East End to administer doses to its frontline workers.

SHINNECOCK STRUGGLES & PROGRESS

The Shinnecock Nation experienced significant developments in 2020, with a landmark law passed to protect its heritage. The “Protection for Unmarked Graves Act” was passed by Southampton Town in September to protect unmarked Shinnecock burial sites, the first law of its kind in New York State. The law establishes a set of protocols if human remains are encountered during construction activities anywhere in the town. But the law was not passed without challenges—in August, members of the nation confronted Southampton Town Supervisor Jay Schneiderman after public hearings on the matter were postponed.

In November, a group of Shinnecock people called the Warriors of the Sun began a month-long protest in the form of a Sovereignty Camp to protest a state-level lawsuit against the Nation over its planned second billboard monument on Sunrise Highway. The camp, held on the Westwoods land, led peaceful protests, as well as a food drive.

Looking ahead, the Shinnecock Nation hopes that New York State will resolve its lawsuit against them so they can proceed with planned economic developments. Shinnecock member Tela Troge said of the Sovereignty Camp’s goals: “What we’re trying to do [is] raise awareness and invite people to come down and become educated on these issues.”

THE CHAINSMOKERS SCANDAL

A drive-in fundraiser at Nova’s Ark in Bridgehampton headlined by EDM group Chainsmokers made national headlines after video ofpeople dancing and singing in close proximity went viral. The state launched an investigation into the “Safe and Sound” concert and Gov. Cuomo was highly critical of Southampton Town for approving the event. Further controversy ensued because Town Supervisor Jay Schneiderman was the opening act for the concert, though Schneiderman left before the violations occurred.

In the end, the event’s organizers, In the Know Experiences, was eventually fined $20,000, while Southampton Town will now require state approval before allowing group gathering permits in the future.

BLACK LIVES MATTER

Cries for justice and the end of police brutality were heard across the globe this year with the names of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Tamir Rice, Eric Garner and countless others on the lips and signs of peaceful Black Lives Matter protesters. Cries rang out from the Hamptons and North Fork, as well, where marches and demonstrations were held in Montauk, Hampton Bays, Southampton, East Hampton, Sag Harbor, Bridgehampton, Westhampton, Riverhead, Shelter Island and other areas.

Teenage siblings Sophia and Kilian Ruckriegel organized the Paddle Out in Solidarity event in August, which attracted more than 80 supporters to Napeague to show their support. On September 5, Southampton Village was host to two very different protests—the Black Lives STILL Matter March & Rally and the Back the Blue Rally—which, like the East End demonstrations before them, remained peaceful. In October, Leon Goodman walked 137 miles from New York City to Montauk as a form of silent protest, having enlightening conversations with supporters and detractors along the way.

Many East End businesses showed their support of the Black Lives Matter movement on social media, though some posts were more controversial than others. Montauk Brewing Co. faced incredible backlash for posting a photo of their chalkboard sign with a message stating the owners would donate to organizations furthering the cause, with thousands of offended Facebook users joining a group to boycott the company.

BONAC BLIND

This year’s most-read story on DansPapers.com was the incident surrounding East Hampton artist Scott Bluedorn’s “Bonac Blind.” A duck blind mini-home created as a statement on affordable housing and the disappearing Bonacker culture, “Bonac Blind” was attacked at its location on Accabonac Harbor in October with dead fish thrown through kicked-in windows, the installation’s town permit stolen and a tire-flattening device placed in the parking lot.

Though he found no solid evidence as to the culprits of the vandalism, Bluedorn predicted that it may have been the work of the very people he was trying to honor who likely felt his art installation was bringing them unwanted attention or who were offended by its placement and message.

The incident was not the first act of seemingly anti-art retaliation in Springs, as Neo Political Cowgirls founder Kate Mueth shared that something similar happened to her in 2014 in response to her dance theater company gaining East Hampton Town permission to take over the Parsons Blacksmith Shop for a two-week installation. After a man in a truck berated her about how privileged Hamptons artists are, she found a 10-foot-tall wall of dirt blocking her out of her driveway. Despite backlash, both remain undeterred in their commitment to provide art to the East End community.