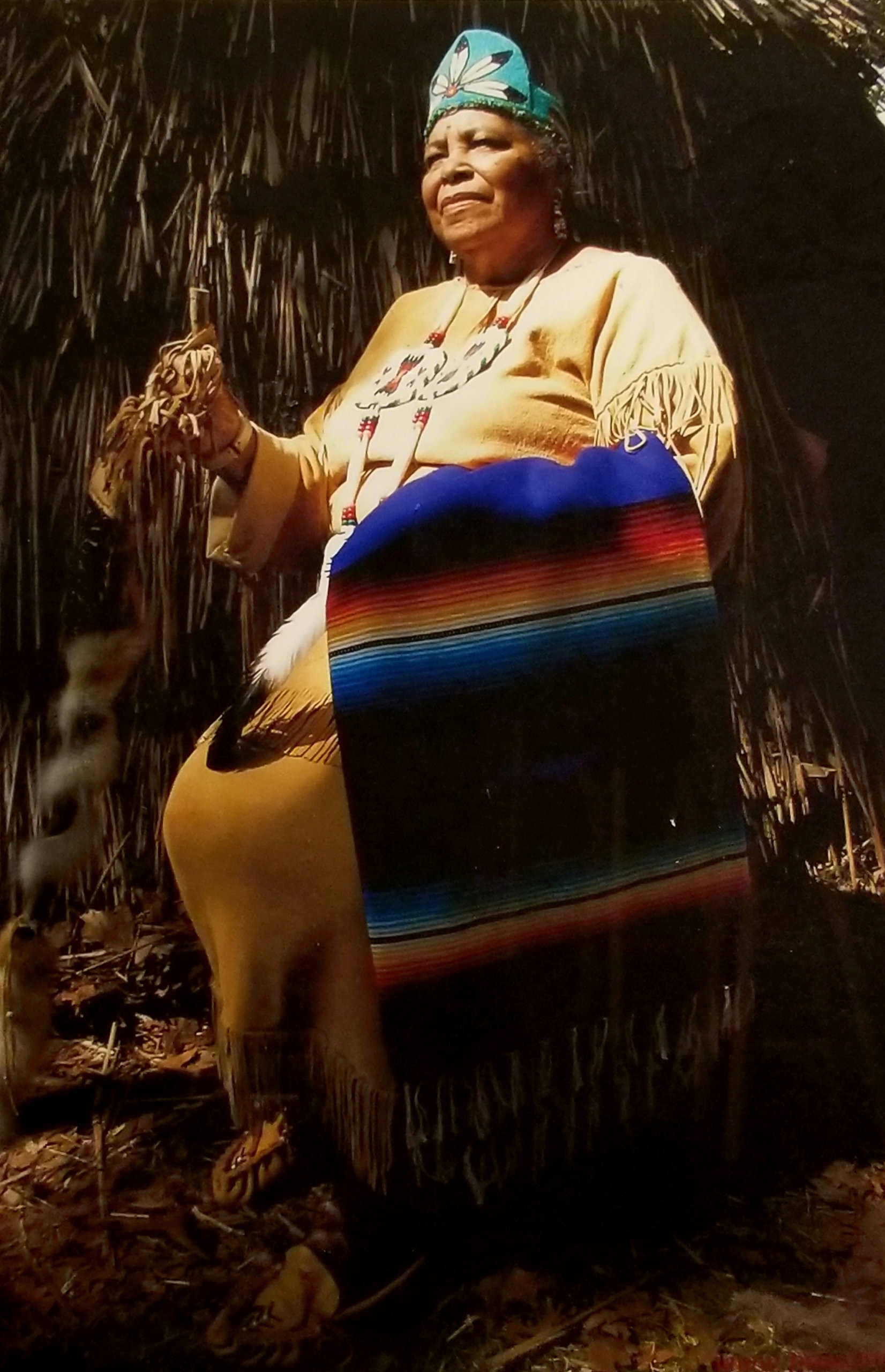

Harriett Gumbs, 99: A Fighter for Indigenous Rights Passes

Harriett Gumbs, the matriarch of the Shinnecock Indian Nation, died the day before Thanksgiving. She was 99.

Born and raised in poverty on the tribe’s reservation just outside of the Village of Southampton, she and her family lived behind Keep Out signs posted at every entrance into that community. Three men were the tribal chiefs. Women were not permitted to speak at tribal meetings, nor were they permitted to vote.

In Harriett’s senior year at Southampton High School, the class went on a school trip to Washington, D.C., where she first encountered Jim Crow. She was required to stay at a hotel separate from her classmates because she was black. She could drink only from a water fountain marked “Colored Only.” She later said this experience had a profound effect on her.

I met Harriett Gumbs, in headband and beaded blouse, when she spoke to the members of the Southampton World Affairs Council in the living room of Southampton College’s administration building. She’d been invited to speak because in just three years, at age 54, she’d graduated summa cum laude from the college with degrees in both history and education, followed by a masters degree in Native American Law from Antioch University. She came across as a warm and engaged individual who had a message to deliver about education, women and tribal affairs. I spoke with her privately afterwards. She showed me a folded up drawing of a museum and cultural center she wanted built on the tribal property. It was in the shape of a tortoise, a sacred creature to the tribe, she told me.

She’d already accomplished a great deal by then. In 1950, she’d opened the Shinnecock Indian Outpost, the first tribal business on Hill Street. In 1972, she wrote a famous letter to President Richard Nixon urging him to add the Shinnecock Reservation to all official federal Indian maps even though the tribe wasn’t federally recognized. She also asked for accelerated federal recognition. The tribe got put on the map. But Nixon never mentioned federal recognition.

In the 1970s, after the town had granted permission to a developer to put 10 homes on Shinnecock land facing Hill Street, she circulated a petition and led a protest resulting in the town reversing itself, even though the foundations of these houses were already built. Subsequently, the foundations had to be jackhammered out.

A year after I met her, she called to ask if I could find work at Dan’s Papers for one of her sons, age 17. He worked a summer delivering papers.

A year later, she asked if I could come to court to attest to his character. This son, Lance, had applied to Adelphi University to study accounting. There had been trouble on the reservation the day before and though he, just a high school student, was with her in the house during this altercation, the police arrested him anyway.

“If he is charged,” she told me, “Adelphi will never accept him.”

I went to Suffolk County jail in Riverhead, where he was being held overnight and the next day spoke in court. Charges were dropped.

Lance Gumbs has since served several terms as tribal trustee and chairman. He’s also an officer in the National Congress of American Indians.

Now I was getting invited to the tribe’s annual Thanksgiving dinners. At these dinners, everybody would, on arrival, pay their respects to Harriett.

In 1985, the Town of Southampton, citing zoning, tried to block the construction of what is now the Shinnecock Nation Cultural Center & Museum even though it was on tribal property. Harriett fought fiercely and got it through.

In 1987, she told The New York Times, “You know, we used to be the good Indians. As long as we were working for them, caddying, cooking, cleaning their houses, we were good Indians. But the minute they see our children become educated, begin to stand up for themselves, we are no longer the good Indians.”

Soon thereafter, the tribe applied for federal recognition. To document the tribe’s longtime existence, Harriett went to France and England and brought back long-ago letters between European leaders and the Shinnecock.

The right of women to speak at the tribal councils was approved in 1992. The right of women to vote in 1994. Harriett joined the League of Women Voters.

Harriett lectured at Harvard, Yale, Penn State and Purdue. And then, in 2010, Harriett at age 89, got to share the tribe’s joy in celebrating the federal government’s announcement of tribal recognition.

She died peacefully at her home. After her funeral, a procession of hundreds of cars—her sons in the first car joined by Southampton Mayor Jesse Warren—wended its way through the streets of downtown Southampton taking Harriett to her resting place. Her collected papers are available to view at the cultural center.