Long-stalled Plans to Preserve Expressionists' Historic Home Splattered in Uncertainty

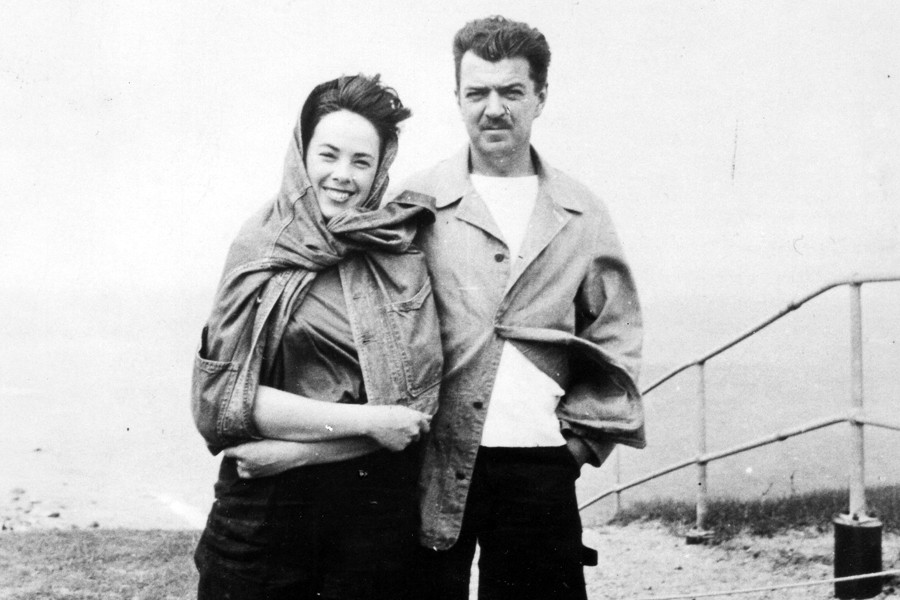

Not since Hurricane Carol destroyed late abstract expressionists James Brooks’ and Charlotte Park’s beachfront studio nearly 70 years, prompting the couple to barge their cottage across Napeague Bay from Montauk to Springs, has the historic structure’s future been so cloudy.

That’s because the Town of East Hampton, which bought the 11-acre property where the house sits on Neck Path for $1.1 million in 2013, last month unexpectedly revoked its contract with Peconic Historic Preservation, Inc., a not-for-profit organization that was hired four years ago to help restore, maintain, and host programming at what is now known as Brooks Park—a move that has sparked as many interpretations as one of his surreal paintings.

“The town board has concerns as to the deposition of funds already donated to Peconic Historic Preservation Inc.,” East Hampton Town Supervisor Peter Van Scoyoc said at the town’s February 18 meeting, noting that New York State authorities would be notified to ensure donations are returned.

The breakdown is a far cry from the goal to replicate the success at Duck Creek Farm, a colonial-era property that later became home to artist Little John, who, like Brooks and Park, were friends with famed abstract expressionists Jackson Pollock and Lee Krasner and was part of a mid-century community of artists drawn to and inspired by the natural beauty of the South Fork.

Robert Strada, the executive director of the nonprofit that sought to restore the Brooks house, did not respond to requests for comment. But his White Plains-base attorney Lee David Auerbach questioned the town’s motives.

“It is totally, completely, a smoke screen,” Auerbach said of the funding issue the town cited. The attorney conceded he did not know what he thinks the town’s ulterior motives are.

Helen Harrison, who’s the director of the Pollock-Krasner House and Study Center and a member of the Brooks-Park Heritage Project, said the group raised $84,302.50 to help fund the preservation of the Brooks house between the town declaring it a historic site in 2014 and the nonprofit being contracted to manage it in 2017. She questioned why the nonprofit spent what amounts to more than double the agreed upon 5% annual overhead fee.

“Why would they spend $30,000?” she asked. “On what? There’s been no programming.”

Auerbach maintains that the funds went toward insurance, bank and accounting fees—and that the town has been provided documentation showing as much.

In the resolution to cancel the contract, the town also wrote that “a considerable period of time has elapsed without necessary restoration work being performed upon the structures at Brooks Park.”

But Harrison and Auerbach each separately used the same adjective to describe the town blaming the nonprofit for the lack of progress on rehabilitating the house: disingenuous.

“It’s not the responsibility of the licensee to restore the property, that’s the town’s responsibility,” Harrison said. “The licensee’s responsibility is to run it … to be the managing partner with the town. The managing plan is to be carried out with the licensee, but it can’t be implemented until the site has been restored.”

HISTORIC REHAB

Auerbach said the nonprofit struck an agreement to split the cost of restoration of the house 50/50. The nonprofit even had an undisclosed financial backer to help fund its half of the work, he added. But what happened after that remains unclear.

“The town expressed interest in restoring the Brooks property and then they reneged,” he said, noting that his client received no prior notification that the contract cancelation was going to be on the town board’s agenda. “All of a sudden they did a 180.”

The town had tapped the Community Preservation Fund (CPF), a New York State-run program funded by a 2% real estate sales tax on the East End, to purchase the property.

State Assemblyman Fred Thiele (I-Sag Harbor), who created the CFP program, declined to comment on the contract issue on the grounds that it’s a local matter, but he said he hopes for a positive resolution.

“I have supported the preservation of this property and continue to believe that the original decision to restore this property is the right one,” he said.

Harrison, the historian who did the research that the town relied upon to declare the property a historic site—she even knew the couple personally when they were alive—was optimistic when the group was brought in. She thought that there would be progress after hitting some stumbling blocks following the acquisition.

“It appeared there would be some movement,” she recalled. “But for some reason it just didn’t happen.”

She said the goal of restoration was an adaptive use for exhibits and public events, but not a full-fledged museum.

“It has architectural interest, it has artistic interest, these people were important members of the abstract expressionist community that summered here,” she said. “It was sort of a no-brainer to make it a historic site because it qualified on so many different levels.”

UNDERSTATED SIGNIFICANCE

Besides Brooks and Park’s role in the arts community, the house itself is historically significant for its origins before they bought it.

The modest cottage was originally built in a Montauk fishing community, but the homes were later sold off to summer residents. When they bought it, the only running water was a hand pump in the sink. After the hurricane blew their detached studio off the bluff on which the house overlooked, they hired a local company to move it closer to the artists community in Springs. As a result, it is the only known surviving house from this historic fishing village.

In March 2020, however, the National Trust for Historic Preservation wrote a letter to the town urging it to stop any plans to raze the Brooks house and to “work with interested parties to develop a plan for the long-term future of this nationally significant site.”

Auerbach is also concerned that the town will demolish it. But Harrison said the town has indicated to her that it hopes to find another nonprofit to take over management of the park.

“The town board is interested in pursuing the preservation of some of the structures at Brooks Park, but does not believe that Peconic Historic Preservation, Inc. is the appropriate entity to operate and maintain the property,” the town board wrote in its resolution.

Brooks’ own words suggest he hoped his work would endure the test of time.

“My painting will occupy others as it has me,” once Brooks famously said. “Whether it does, and how soon, depends on things we cannot know—the ultimate power of the painting and the need felt for it.”

But for now, it seems the artists’ wishes, like his original Montauk studio, are in the wind.