Ice Age Leftovers: When People Can't Agree on What Should Be Done with the Heavy Stuff

The massive amount of earth left behind by the last glacier when it retreated and created the South Fork includes huge boulders. Many of them turn up where a foundation is being dug for a new home. You can either pay the unexpected cost to remove them or incorporate them into the project somehow.

The Montauk Library decided on incorporation when a 24-ton glacial boulder was found underground while they were digging a hole for the foundation of an addition. They called the contractor, The Patriot Organization, which in turn called Keith Grimes Construction, a subcontractor with heavy equipment such as earthmovers, cranes and backhoes to haul up this boulder and place it on the lawn where, someday, a bronze plaque could be affixed upon it.

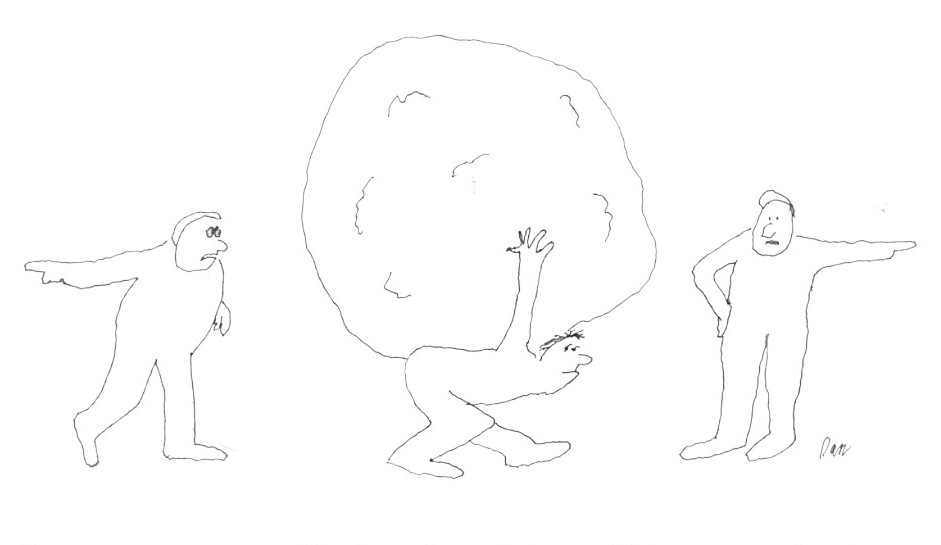

But when a backhoe got the boulder in its maw, David Grimes got into an argument with a representative from Patriot. Grimes had not been paid for his earlier work on the site in more than 100 days, he said, so he either wanted to get paid then and there or they were going to take the boulder away as security. A big boulder like that can be worth $10,000 to a landscaper messing with the bushes and gardens on a big estate. In the end, after the library would not intervene, the police were called and told Patriot this was a dispute about money and no crimes were being committed. And so the backhoe operator gently set the boulder onto one of the Grimes’ flatbed trucks, secured it with chains and drove it away. Nobody could stop them.

“We have it now in our yard in Bridgehampton,” David Grimes told me. “We’ll see what happens.”

Over the years, in Dan’s Papers, I’ve written numerous stories about giant boulders. Some get taken away. Some never get moved. Some result in legal battles.

One pair of boulders, chiseled into giant griffins, sits guarding the entrance to Home Sweet Home Moving and Storage in Wainscott. You see them when you drive by.

These griffins were put into storage there about 50 years ago by a sculptress from Maine who had created them. Twenty years later, she wanted to pick them up. But she was so far behind in paying the storage that in the end she just abandoned them.

David Grimes is the third generation of the firm now known as Keith Grimes Construction. David’s father is Keith Grimes, his grand uncle is Charlie Grimes. And in the course of running Dan’s Papers, I had numerous conversations with Charlie about boulders and concrete projects.

Charlie once told me this amazing story. I wrote it for the paper but often wondered if it were true.

The story goes that in 1941, the Navy built a Torpedo Testing Station on the hundred acres between the Montauk Railroad Station and Fort Pond Bay. If the torpedoes performed properly when set off into the bay, they were sent off to war. If not, they were packed back on railroad freight cars and returned to a factory in Queens for repair.

This testing station, about a dozen large buildings all made of concrete and cinder block, was well over 100,000 square feet in size. But when the war ended, the Navy just walked away, abandoning it.

In 1980, Charlie Grimes was hired to level the abandoned Navy base so it could be replaced with the Rough Riders Landing condominium resort. He sized it up. It was so enormous, he decided to bash it down with a wrecking ball and pile the rubble to create an eighth-of-a-mile-long 8-foot-high berm to separate the railroad tracks from the proposed condominium.

One woman in East Hampton with a loud voice objected to this. It would desecrate the landscape. And the East Hampton Town Board – Montauk is a hamlet in East Hampton – sided with her. The application was rejected.

“So I got this idea,” Charlie told me. “Up in the Montauk woods was the town dump. For $50 you could get a permit to bring stuff there. So I went over and paid the 50 dollars. Where it said to describe what was going to be dumped, I wrote ‘building material from the Montauk Naval Base Torpedo Testing Station.’ And with that, I got the permit.”

Truckload upon truckload upon truckload of the torpedo testing station was taken to the dump. It took two months. And the torpedo testing station essentially filled the dump. All for 50 bucks. Now it’s a transfer station.

Charlie swore this story was true. And last year when I asked Keith Grimes about it, he confirmed that was what happened.

And I have my own boulder story. A giant boulder was found on some farmland on the North Fork by sculptor Jeffrey Parson. He dragged it to his studio and crafted it into a work of art using a chisel and hammer. You could sit on one part of it. He showed me the work once and told me he had a commission to deliver it to the front lawn of Guild Hall in East Hampton. I wrote about it.

But when the time came, the Village of East Hampton would not approve. There already was a sculpture on that lawn. The limit was one sculpture.

At the time, the Dan’s Papers office was on Main Street in Bridgehampton. I made Parson an offer. If he wanted to, he could put the boulder on my front lawn. He asked if I wanted to buy it and I said no, but he could keep it there until it was sold. It would be quite prominently displayed.

Many people sat on the boulder over the years, but it never sold. In 2012, I sold the building. But what about the boulder? The building buyer said he didn’t want it. Just take it. So I called Parson, who had relocated to Garberville, Calif. after a divorce, and asked him to move it off and was told by his girlfriend that Jeff had a band playing clubs in a beach resort in Uruguay, South America and was now living there. But I could call him there. So I did. He said, “Well, whatever.”

When I was unable to find any place to take the boulder, I sold the property with the sculpture on it. A year later, the sculpture was gone. I don’t know what the new owner did. And I am not asking. Our office is now in Southampton.

Boulders. Can’t live with ’em, can’t live without ’em.