Our Amazing History: The Circassian Shipwreck

Just after a bitter cold Thanksgiving in 1876, a winter storm hit the Hamptons. It was not particularly bad at first, but it hung around. On December 11, those on the beach saw a very large cargo ship stuck on a bar 400 yards off Mecox Bay.

The ship was the Circassian, and its grounding became a disaster of such proportions that many involved remembered it for the rest of their lives.

The Circassian had been built in 1856 as a 280-foot-long iron-hulled freighter with both sails and steam engines. Ten years later, the steam engines, now very old and out of date, were removed. This gave it an even larger capacity for carrying heavy cargo.

But now it was entirely powered by sail.

The Circassian left Liverpool on November 6, 1876 bound for New York carrying, among other things, 41,000 bath bricks (scourers), 600 tons of caustic soda, 280 barrels of soda crystals, 87 casks of bleaching powder, 281 bags of hide pieces, 100 cases of sauce and much else, totaling 1,400 tons of industrial freight. The crew totaled 38.

Officers from three different life-saving stations—Mecox, Southampton and Georgica—were soon on the beach with others eager to help. Also soon arriving were freight agents from New York City, men from the Coast Wrecking Company and the wreck master, a government agent who was on hand to see that cargo is delivered to those people for whom it was intended.

Small boats were sent out to remove some of the crew. Sixteen remained, and soon greeted Captain John Lewis of New York, a former master of the Circassian, taken aboard to supervise the transfer of the cargo to small boats. He arrived at the Circassian with three engineers, two local men and 11 young Shinnecocks from the nearby reservation.

On December 27, the storm turned into a full-blown nor’easter. All were of the opinion this was a good thing because the Circassian, now lightened, would break free on a high tide. But the situation just got worse and worse.

Finally, only one small boat could get through. Tied alongside, its captain, Luther Burnett, announced this would be the last boat and all should climb in and be taken to shore, but Captain Lewis refused. He was still convinced the ship would lift and get off.

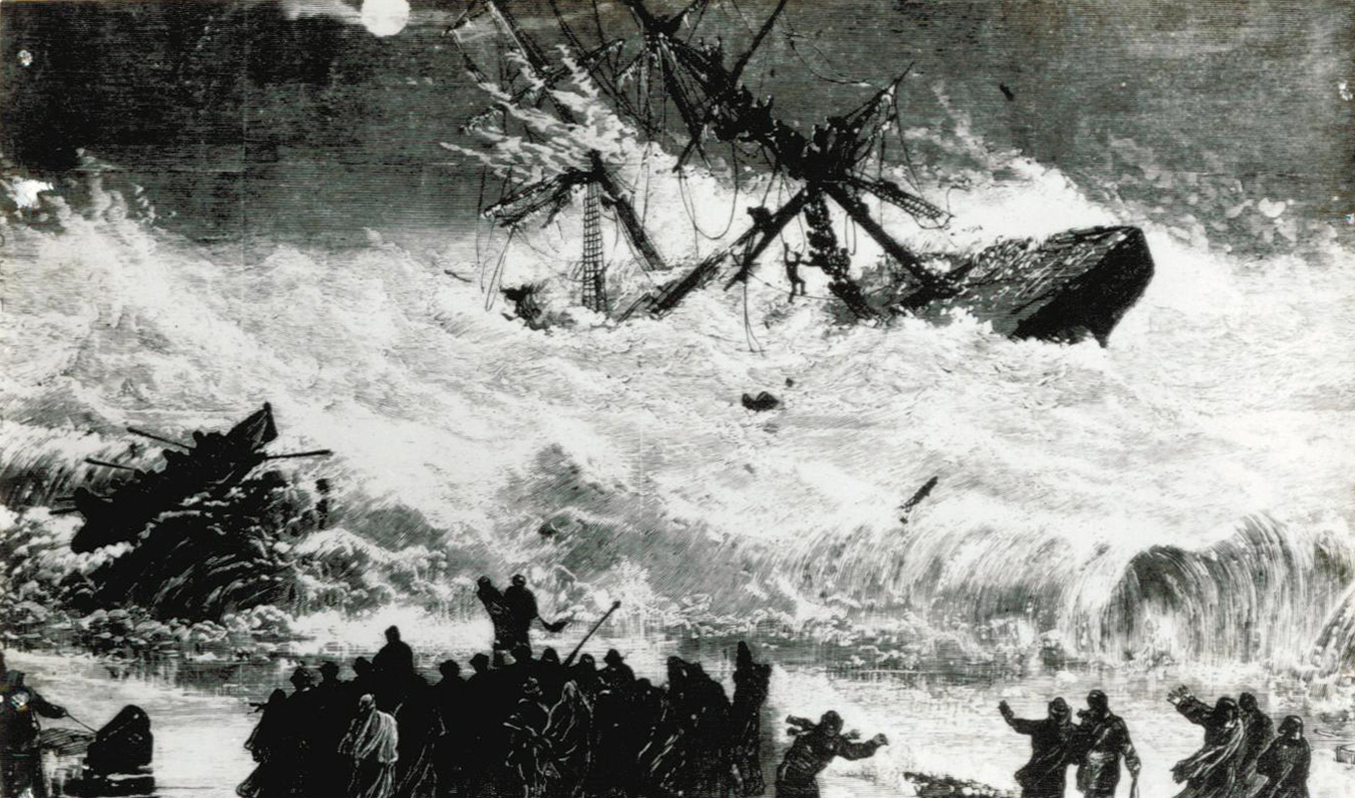

It never did. Soon waves crashed over the hull and in the freezing rain, those aboard climbed the iron masts to keep clear of the ocean. Late at night, people ashore saw men in the rigging covered with ice, many of them Shinnecocks who could be heard singing and praying until they died.

The next night, December 30, the ship split in two and sank. Soon bodies were washing ashore.

Ten Shinnecock men—David Bunn, J. Franklin Bunn, Russell Bunn, William Cuffee, George Cuffee, Warren Cuffee, Oliver Kellis, Robert Lee, John Walker and Lewis Walke—were buried on the reservation. An eleventh, Alfonso Eleazer, had wisely taken an earlier boat to shore. The bodies of Captain Lewis and three engineers were taken to New York.

The remaining 14 workers were buried in the graveyard in East Hampton by Town Pond.

At this time, there were only about 175 people living on the reservation. It devastated the Tribe, but there were 25 children among them and they carried on.