Eric Fischl’s Saints of Sag Harbor: Part VII

The religious past and the art-as-religion future have intersected within the walls of the Sag Harbor Church, a cultural hub with famed artists/activists April Gornik and Eric Fischl as the founders, and Sara Cochran as executive director.

The soaring building is home to 20 windows; it is there, explained Fischl, where the “arts saints of Sag Harbor, the dead saints, will be canonized.” Fischl’s artistic contribution to the historical narrative of those of who were drawn to the East End as a vortex of creativity shine down from the portals surrounding the space.

For more information about programs, visit sagharborchurch.org.

Dan’s Papers is showcasing two windows a week for 10 weeks, with Fischl’s lighthearted responses when asked the irreverent question, “What would this luminary be the patron saint of, besides Sag Harbor?”

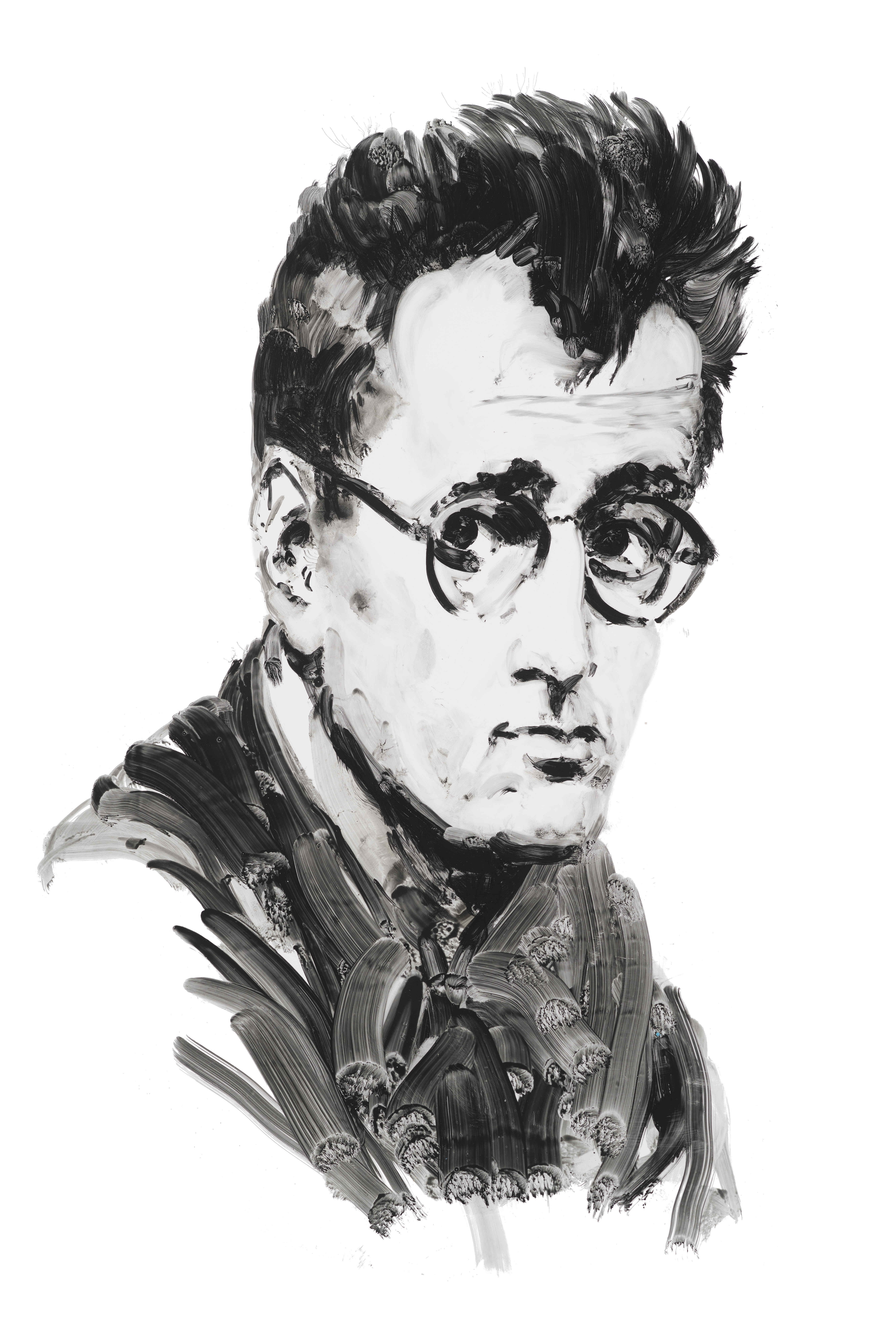

Nelson Algren (1909–1981)

Fischl: “Nelson Algren is the saint for those creative gangsters who splash light, language and color on the pounding jukebox of hard living.”

Nelson Algren was an American novelist and short story writer, known as the “Poet of the Chicago Slums.” His novel The Man with the Golden Arm, published in 1949, won the National Book Award and was adapted as a 1955 film of the same name.

Algren showed his tough love for Chicago with Chicago: City on the Make, published in 1951, and was referred to as “a bard of the down-and-outer,” reifying the world of the Chicago demimonde. He moved to Paterson, NJ after researching and writing about the boxer Rubin “Hurricane” Carter in The Devil’s Stocking.

Hemingway called Algren the greatest post-war novelist writing in his day. He moved to Sag Harbor at the end of his life, somewhat embittered by his lack of fame. Algren was then accepted into the American Academy of Arts and Letters, and planned to celebrate his induction, but died in his kitchen while preparing for a celebration party.

Betty Friedan (1921–2006)

“Betty Friedan is the saint of housewives with much more on their plates than domesticity,” Fischl says.

In 1963, Betty Friedan published a book called The Feminine Mystique that galvanized American feminism in the second half of the 20th century. By the year 2000, more than three million copies had been sold, and it had been translated into many languages. The Second Sex, an earlier book by French author Simone de Beauvoir, also dealt with similar issues but did not quite strike the same cultural nerve. The Feminine Mystique exploded the pervasive myth that a woman kept by her husband in a housewifely role is necessarily a fulfilled woman: “The problem that has no name,” as she called it.

The publication of The Feminine Mystique also led to her cofounding and presidency of the National Organization for Women in 1966, which sought equal rights and standing with men in American society. This was followed by the Women’s Strike for Equality in 1970, which took place on August 26, the 50th anniversary of the 19th Amendment to the Constitution, which gave women the right to vote. She was slow to accept the cause of LGBTQ rights, but eventually saw its essential worth.

There is no question that Friedan’s book and work has had an enormous effect on culture worldwide, and its importance is undiminished.