Our Amazing History: Harold Fish’s Last Day

On the morning of what would be the last day of his life, stockbroker Harold Fish, age 47, woke, dressed in his suit and bow tie, looked out at Central Park from the window of his posh New York City apartment at 1150 Fifth Avenue and went to work downtown.

At 3 p.m., as the boss of Reynolds & Fish, he left early to catch the Long Island Rail Road’s 4:19 Shelter Island Express, a special Friday afternoon high-speed train pulled by two steam locomotives that would take him to Greenport in just two hours. From there, servants would meet him and drive him to his waterfront mansion in East Marion for a summer weekend with his family.

It was raining that day, August 13, 1926 — Friday the 13th. And though the train was supposed to cruise along at 70 miles an hour, on this day, because of the weather, it fell behind schedule.

As the train passed Manorville at 5:35, however, the rain stopped. The engineer turned to his fireman and ordered more coal. He’d make up the time.

Fish, seated in the luxurious parlor car behind the two engines but in front of 10 regular passenger cars, did not feel the acceleration.

In this lone parlor car, the walls were polished mahogany, the ceiling carved with cherubs, the floor covered with Turkish carpets. Millionaires normally sat in the eight upholstered easy chairs in this car. But on this particular trip, Fish had the whole place to himself.

With a snap of his fingers, he could order porters with white gloves to bring him his newspaper, a cigar, or a Scotch and soda, and make an adjustment to his lamp or the heavy curtains alongside the windows. The view outside was a blur of farmland and fields. Occasionally a track siding led out to a loading dock. There were vegetables, fish and other goods to be shipped west to New York in freight cars. Of course, the Shelter Island Special never took on commercial freight.

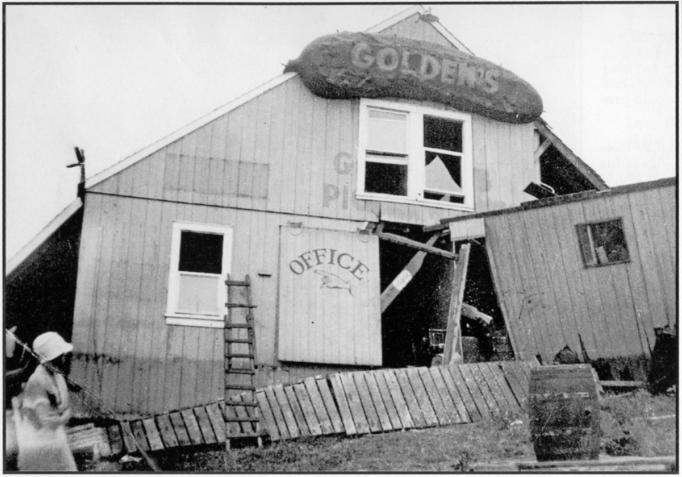

Just past the Edwards Avenue crossing in Calverton, alongside the tracks, stood a two-story barn being used as a pickle factory. Loads of locally grown cucumbers arrived at the back door. Inside, huge barrels of salt, brine, pickles and spices sat on overhead rafters, as workmen below pulled ropes opening them briefly to send ingredients down chutes and into jars on conveyor belts as they passed. Toward the end, the men capped and labeled the jars, then loaded them into boxes and set them on the siding. Above, a 12-foot plywood sign in the shape of a pickle read “Golden’s Pickle Works.”

Earlier that afternoon, because it was Friday and it was hot out, the foreman had sent the workers home at 4 p.m. Normally they worked until 6 o’clock. After they left, the foreman locked up and checked the metal railroad switch to see that trains would not be sent off onto their siding. He never noticed that a small bolt, holding a cotter pin in place, was loose.

The first engine went straight, but its speed shook the nut off the cotter pin and caused the switch to change. The second engine lurched down the siding, pulling the first engine sideways and causing the second engine with the parlor car attached to climb the first engine and crash down into the barn, collapsing the structure inward. Fish was thrown up through a split in the parlor car’s roof and back down onto the floor of the pickle works, where a mishmash of broken glass, brine, pickles, barrels and mostly salt covered him and suffocated him to death.

The lead locomotive engineer and fireman as well as two young children and their mother died too in what would come to be called the Great Pickle Works Wreck. But the rest of the 337 passengers in the regular cars behind survived. Those cars never left the tracks.

It took five days to clear the mess. An obituary in The New York Times ends with “…he inherited the ingratiating qualities which so distinguished his father, and the most heartfelt sympathies of a host of friends go out to his widow and young children.”

He lies buried in Sterling Cemetery in Greenport.