Moby Dick: A Book Primer Before Sag Harbor Marathon Reading

Every summer, the novel Moby Dick is read aloud by a series of writers, historians and celebrities here in Sag Harbor. It takes them three days. And that’s because they read it slowly, chapter by chapter, from beginning to end. This year, the first chapters will be read at Canio’s Books starting on Friday, and further chapters will be read at the Sag Harbor Whaling & Historical Museum, the Old Whalers’ Church, Eastville Community Historical Society, The Church, John Jermain Memorial Library and then on Sunday from 1–5 p.m. back at Canio’s Books for the grand finale.

Sag Harbor is not the only place where Moby Dick gets an annual reading. It is read in New Bedford, Nantucket and Lahaina, Maui. These three ports, together with Sag Harbor, were the four major whaling towns in the world and from them hundreds of three-masted whaling ships headed out on the high seas to kill whales from the mid-1700s to around 1860.

The world craved whale oil to light and heat their homes back then. And in these port towns, people from all over the world talking in dozens of languages lived and worked, having disembarked from whaling ships that stopped to drop off sailors and take on new ones. Back then, coopers and blacksmiths, sailmakers and inn keepers, captains, mates, woodworkers and harpooners lived along the dirt main streets of these communities passing their time in rooming houses, bars, warehouses, whorehouses and gambling dens.

Sag Harbor’s Main Street was largely built during this period until, in 1849, with whales harder and harder to find even from halfway around the world, nearly the whole fleet left town to join the gold rush to San Francisco.

Herman Melville was 32 and a successful author of adventure novels when he got the idea to write Moby Dick in 1850. Earlier, he had made several voyages to far-off lands. The first was aboard a freighter, but another was as a crew member and harpooner on a whaling ship which, got him to Lahaina and then back home. Two earlier novels about the South Seas Islands were successful. But as it turned out, his masterpiece Moby Dick was not. It faded into obscurity as an oddity and he got little benefit from it. It was only when it was rediscovered in the early 1920s, long after he was gone, that it was declared his masterpiece.

Here is my book report about Moby Dick. I think it is now considered an American classic for the very things that others found annoying because they got in the way of the narrative.

These essays are about religion, politics, greed, insanity, obsession, ethics, morals and even poetry. It depends how you look at it.

“Call me Ishmael,” are the first three words in the book. Ishmael is the narrator, introducing himself as a New Englander fascinated with the sea for its ability to calm and soothe him through troubled times. This is why he wants to go out whaling.

A ferry takes him from New Bedford to Nantucket to find a whaling ship where he can gain employment. Tired after an unsuccessful first day, he finds a cheap rooming house where he’s told all the beds are taken. However, there’s this harpooner from the South Seas staying in one room that he’s not in now, and the innkeeper is sure he wouldn’t mind if Ishmael shares half of that bed for a night.

Ishmael is a little concerned at this, but takes the innkeeper up on it, eats a hearty dinner and then goes to the room and to sleep.

At midnight, he’s awakened by the islander Queequeg, who is trying his best to tiptoe around. The islander is a 6-foot-tall “savage” covered with tattoos. He sits, sets a small wooden statue of a god on the mantel, and very quietly prays to it. Then he places some shrunken human heads next to the god, takes off his clothes and, carrying his harpoon, gets into bed. There, to keep warm on this cold night, he throws one of his arms over Ishmael for body heat while Ishmael pretends not to notice. Is this fellow a cannibal?

He isn’t. In the morning, communicating by sign language and broken English, they become friends and agree to go aboard the same ship if it can be arranged. They learn a whaling ship called the Pequod is about to leave, but the captain is crazy and has a peg leg because a white whale attacked him on an earlier voyage and ate his leg below the knee. And the captain is obsessed with getting revenge.

They walk out the wharf. Be careful of this captain, a stranger tells them. But they shrug, spend time at a church service (with Queequeg staying outside) and then find the boat. There’s no captain onboard, but two owners are there, sitting in chairs, checking in the supplies that deckhands are carrying aboard, intended to last three years.

And the captain? Ahab? Both say he’s a little queer but otherwise quite nice. You’ll meet him, they say, but they are authorized to hire a crew for the trip. So both get hired, Ishmael for a small fraction of the ship’s profits and Queequeg for twice that.

The owners leave and the captain arrives, an old man who says nothing to anybody and goes quickly below. Finally, they sail out to sea and after two days, the captain emerges, nuttier than a fruitcake. He’s going to kill that white whale. Nothing else matters. And now, there’s no way off this ship.

Melville writes about the different crew members, about the cabins and decks and lookouts atop the masts. He then presents several chapters discussing the different detailed illustrations of sperm whales that dozens of prominent artists down through the ages have drawn and how almost all are wrong. All have never seen a whale. He has, he tells the reader.

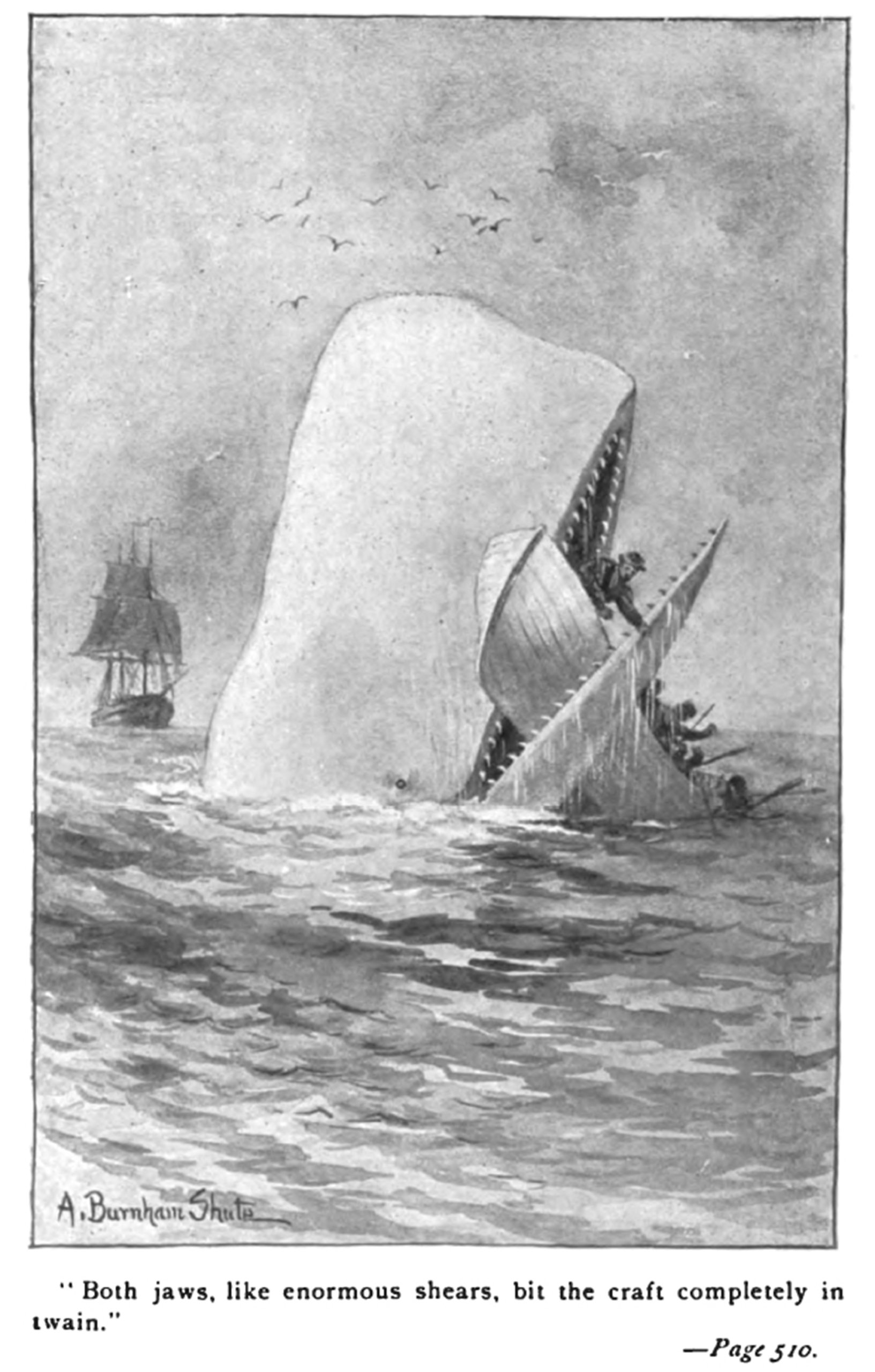

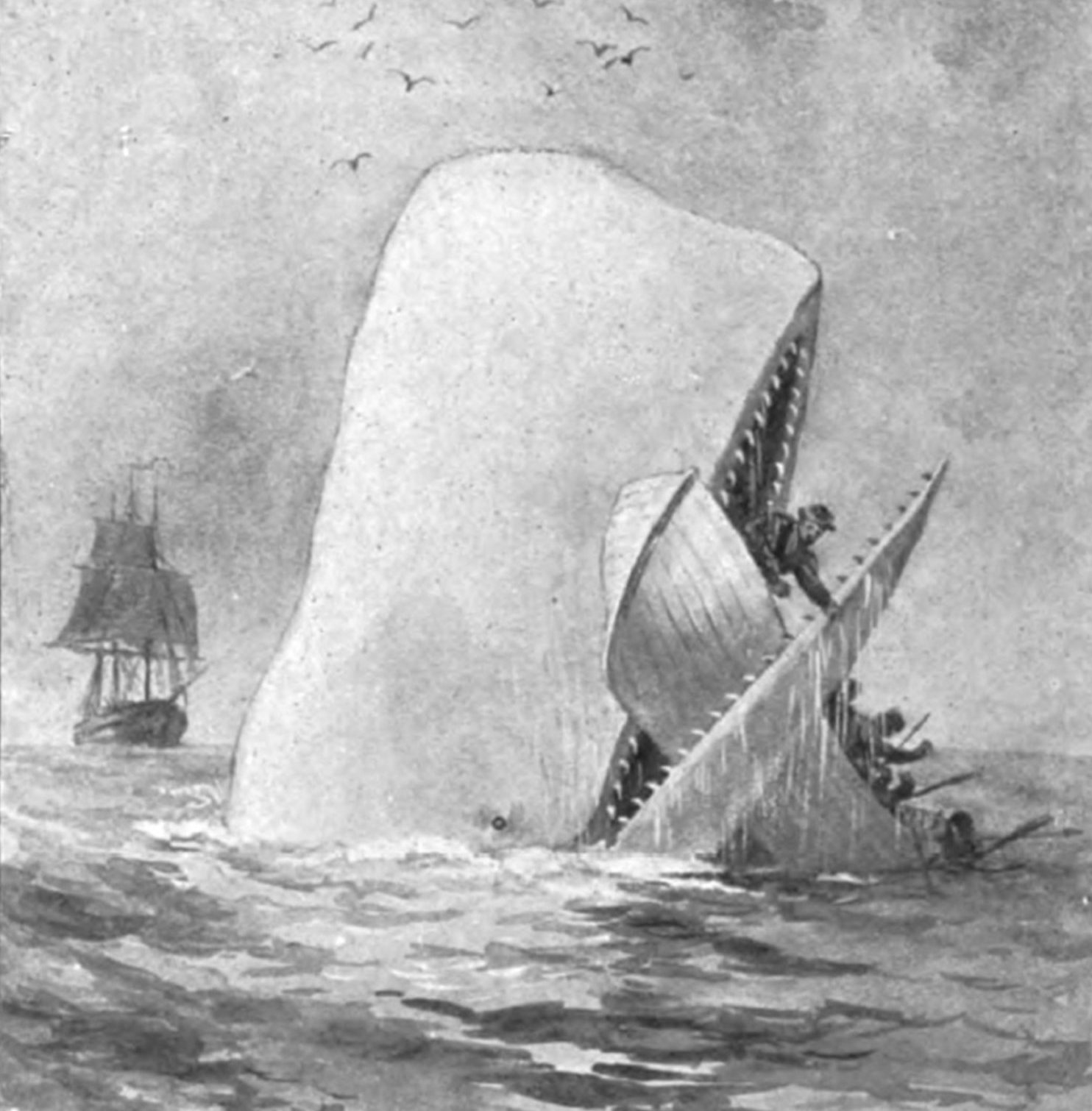

In the end, after a violent struggle, Moby Dick kills and eats the captain, then rams the Pequod and sinks it. Its vortex pulls the four small whaleboats down into the sea—and only Ishmael survives to tell the tale.

And that’s Moby Dick.