Our Amazing History: The Wreck of the John Milton

On February 20, 1858, John Stratton, whose family operated the Third House Inn in Montauk, rode on horseback down to the beach near Ditch Plains in that town. It was a bitter cold morning, but the sun was shining now. Gone was the brutal gale that had pummeled the East End with blinding snow, wind and rain for three days. Maybe good things had washed ashore. They often did after a storm in those days. He’d walk his horse along the beach and see if he could find anything. Back then, like now, it was finder’s keepers.

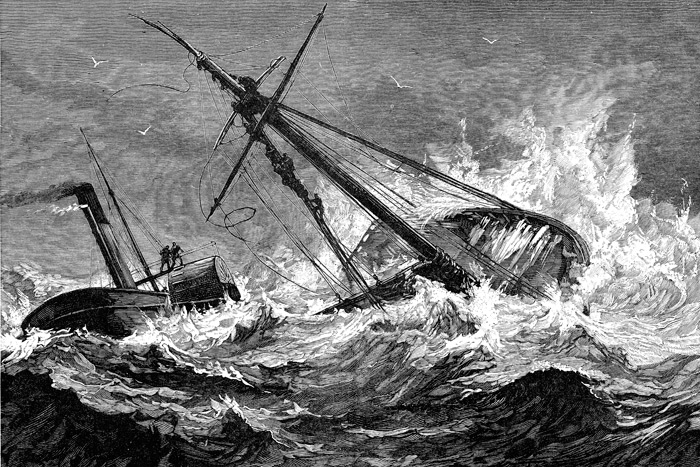

Stratton came upon one of the most horrible sights imaginable. The wreckage of a 203-foot-long three-masted schooner lay before him, bow in, as if it had come ashore at full speed. The tattered sails were still up. The force of the wreckage had split the wooden ship in two and scattered parts of it all over. Among the wreckage were the dead bodies of more than a dozen seamen, all frozen solid by the ice, some separate, some clinging together, all having washed up. Stratton galloped home.

Later that day, a rescue party arrived at the scene, together with the county wreckmaster, a man whose job it was to guard whatever cargo had been onboard from looters until the proper owners would arrive. The ship was the John Milton out of New Bedford, Mass. Its cargo was barrels of guano, used back then as fertilizer on farms. But most of the barrels had split open in the crash with the contents washed away. And none of the 33 crew members and passengers onboard survived.

The townspeople of East Hampton — Montauk was pastureland back then except for three inns — were stunned by this tragedy. They wrapped the bodies in shrouds and by horse and wagon took them to the East Hampton Town green where they were laid out in rows. The town’s Presbyterian minister officiated at the funeral service. All except the captain — to judge by his uniform — and his teenage son were buried in the South End Burial Ground in a common grave with a marble marker atop it. The captain, identified as Ephraim Harding, and his son were was taken away and buried in Martha’s Vineyard. And four more bodies, which washed up later on as far west as Mecox, were added to the common grave as they were brought in. A use was found for the ship’s bell. It was hoisted up into the sessions house of that church where it remained for a hundred years, clanging every hour.

Days later, the ship’s log was found. Out of New Bedford, it had gone into the Pacific where, at one of the Chincha Islands off Peru, it had taken onboard the guano. It then rounded the Horn, came north through the Caribbean and into the approach to New York City where the barrels were to be delivered. Encountering the storm, the captain decided to turn the ship east to get away from it, then, traveling along the shoreline of Long Island, get guided around Montauk from the lighthouse there into Long Island Sound for a safer approach to Manhattan.

Just seven weeks before, a new lighthouse at Shinnecock had been activated, its light lit by oil. The captain had not known of this. Through the storm, sailing west along the coastline, he’d seen the welcoming light of the Fire Island Lighthouse. The next light, or so he thought, would be at Montauk. What he rounded, however, was the new Shinnecock Light, which was midway between Fire Island and Montauk. As a result, when he ordered the John Milton north under full sail, he came roaring ashore into Ditch Plains and destruction.

Many people mark the wreck of the John Milton as Long Island’s worst shipwreck. As for the Shinnecock Light, in 1948 it was dynamited down, considered surplus property during one of the Coast Guard’s periodic belt-tightening procedures.