The First Thanksgiving Was Really in Montauk

Most people believe that the first Thanksgiving dinner in America took place in Plymouth, Mass. in the year 1621. It was a joyous event celebrating the end of the fall harvest and the bond of peace between the English settlers and the local tribe of American Indians.

But now, three recent discoveries have led archaeologists to the conclusion that this dinner was not the first. It turns out that a celebratory dinner between white men and the Montauk Native Americans took place more than 600 years earlier when the Montauk Indians hosted a dinner with 50 Vikings atop of Fort Hill in that town.

The first of the three discoveries leading to this conclusion came in October 2021 when, in L’Anse aux Meadows, Newfoundland, Canada, the remains of eight sod and timber buildings imbedded in the ice there were subsequently carbon dated to the year 1021 — 1,000 years ago.

The second discovery took place this past February, when a piece of a wooden bench was found in the dirt atop Fort Hill that carbon dates, with precise accuracy from measurements made at Fresh Lake University in Voorhees, New Jersey, to November 25, 771, a date even earlier than the discovery at Newfoundland.

And the third discovery happened this summer when new boulders were found at a former Viking settlement in Norway called Bryggenskipett that have elaborate accounts in the Runic language carved on them describing this very encounter during that earlier year of 771. (The account calls the place “the Wstern Lnds” and the Montauks “the Mtakk People” because the runic alphabet has only 16 letters in it). It is from this account that this story can be told.

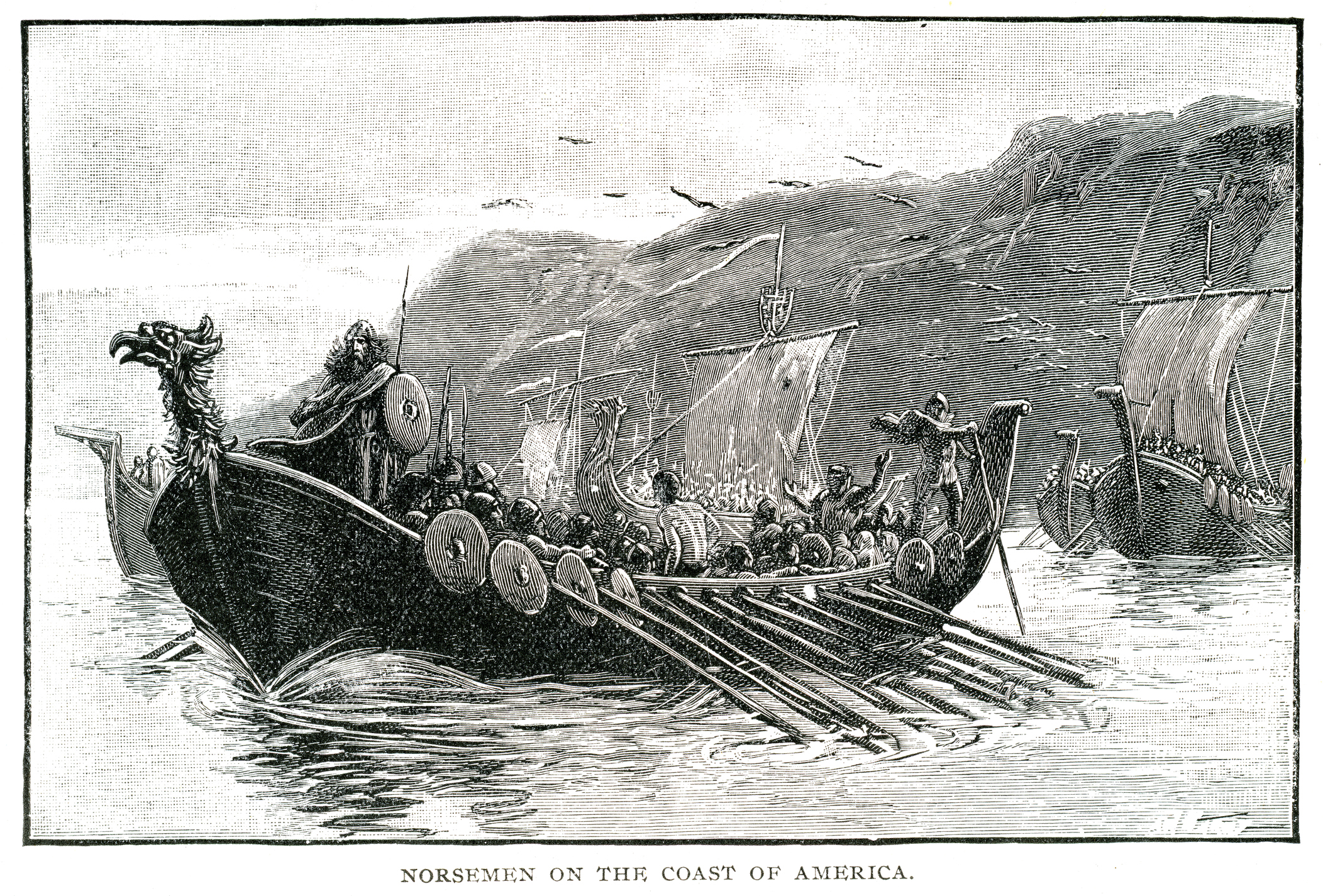

The arriving Viking party consisted of three enormous longboats with fierce dragon heads at the front, each canoe powered by the rowing of 50 strong slaves overseen by 20 Viking soldiers using whips. Here, 23 days out of Norseland, the ships arrived at a great bay with a hill at the back crowned by a large fort made of leaves and branches.

At the urging of the Vikings, the slaves slid the canoes onto the beach enabling 45 of the 60 Vikings, each carrying a club, to jump out. The remaining 15 were left behind to oversee the slaves.

This was the Viking’s annual trip to other lands where Vikings could round up unsuspecting Indigenous Americans and bring them back as new slaves for the Norse people at home. A trip earlier in the year to a closer shore (it was in Ireland) had been aborted when bands of fierce warrior women drove them off. So this new trip was especially important.

On the beach, the Vikings were met by 80 smiling Mtakks – fishermen – who’d seen the canoes arrive and who’d dropped their gear to run over and happily greet these well-turned-out strangers.

Neither side spoke the other’s language, so when the Vikings said they had come to capture and enslave some people, the Mtakks, not understanding, instead made the right hand palm-facing-front gesture of peace and pressed the Vikings to follow them up the hill. The Vikings shrugged but then agreed. They wanted the biggest and strongest to bring back, after all. Perhaps they were up the hill.

Climbing breathlessly accompanied by the excited Mtakk, the Vikings now saw a smoky fire at the top and hoped, since they were hungry, that they would be offered some food and beverages to celebrate their arrival. Also, there might be more Mtakk up there. They’d be able to choose wisely but the capture could wait through dessert.

Arriving at the top of the hill, the Mtakk leader, who wore necklaces, fur scarves, and mocassins, spoke and made gestures of welcome to the Vikings. The fire was burning and things to eat were being brought in. The Mtakk leader then gestured toward the canoes on the beach below until the Vikings understood that though the Mtakk were bringing food, as a courtesy, the Vikings should return to their canoes briefly and bring some of theirs up, too.

The Vikings also noticed that the feasting place consisted of bowls set on ground blankets surrounding a fire right on the edge of the brow of the hill looking down at the harbor. It was a great view. But as eating while sitting on the ground would be uncomfortable for the Vikings, the Vikings returned not only with lots of food but also with a long bench upon which they could all sit.

This must have been the bench recently found.

The Mtakk brought turkey, fish, corn, maize, potatoes, beans and vegetables (carrots, broccoli and squash) while the Vikings provided the meat from elks, moose, reindeer and bears, along with many gallons of a tangy drink called mead. Dessert from the Mtakk was pumpkin pie. Dessert from the Viking leader was a special chocolate babka of bread.

As the meal was being served, speeches were made by the Mtakk leader, gesturing and smiling, about the bond between these two people and the joy in having met them. And by Thor, the Viking leader, who described the wonders that awaited what he hoped would be 40 Mtakks they could round up and bring out to the canoes and back to Norseland. The meal went on for three hours.

But when it was over, and the Vikings started rounding up Mtakks in a rather forceful way, others leaped out from behind trees in an adjacent wood, and using strange contraptions involving curved pieces of wood attached to quivering strings the Vikings had never seen before, fired thin spears above the heads of the visiting Vikings, and then when one of the Vikings lifted up a heavy club and advanced, shot him with a single arrow in one of his buttocks.

The Vikings then ran down the hill as fast as they could, leaving the bench behind, crossed the beach, hopped into their giant longboats and fled. No Mtakk went with them. And the Vikings were never seen again.

So this was the first Thanksgiving dinner in America.

* * *

As we go to press, we learn that a surfcaster has just found a Viking coin in the surf at Fort Pond Bay. The head of a Viking appears on one side and the words “ 2 kroner” appear above “In King Harald We Trust” on the other.