Past Meets Future with LIU's Digitizing History Project

The hard work of preserving history has long been left to the unsung heroes at public libraries, universities, government archives and, especially here on Long Island, local historical societies. It’s within these mostly underfunded institutions where stewards of our past spend hours thumbing through aging records, difficult-to-read handwritten letters and journals, or exploring old photographs to extract stories from bygone days. But recently, thanks to a $1.5 million grant from the Robert David Lion Gardiner Foundation and the team at Long Island University’s Palmer School of Library and Information Science, the picture of our past is becoming a bit clearer and more accessible for anyone who wants look.

Started about five years ago, the groundbreaking and important “Digitizing Local History Sources” project has successfully brought more than 65,000 pages of historical materials from 45 participating Long Island historical societies into the bright light of the world wide web.

The project’s director, Dr. Gregory Hunter, brought a strong resume of talents to the endeavor. He was hired as a professor at LIU’s Palmer School, the region’s only library school, in 1990 to establish Long Island’s first archivist training program, and he’s been doing just that for over three decades. But the past five years have added more layers to what he and LIU can offer archivists in training — not to mention what the RDLGF project is giving the public at large.

“So much of Long Island’s history exists now because of dedicated volunteers who for years have been caring for these materials, but the public never knew what they had,” Dr. Hunter says. “This has been a long-term goal, a long-term interest of the Gardiner Foundation,” he adds later, explaining that RDLGF wanted to get the small historical society collections known to everyone and to reveal the stories within them.

While the work continues, and the grant money dwindles, Hunter and his participating graduate students have already done much to illuminate the history of Long Island communities in both Nassau and Suffolk counties, including a strong East End contingent. Over the last half decade, 10 historical societies from the Hamptons and North Fork have applied and submitted materials to the projects, including Westhampton Beach Historical Society, East Hampton’s Madoo Conservancy, the Ladies Village Improvement Society (LVIS) of East Hampton, Hallockville Museum Farm in Riverhead, Stirling Historical Society of Greenport, Orient’s Oysterponds Historical Society, Shelter Island Historical Society, Southold Historical Society, Southampton History Museum and the Railroad Museum of Long Island in Greenport.

Together, the resulting documents — which can now be viewed on the project website, liu.access.preservica.com — are a feast for hungry history buffs and researchers seeking a window into the past. Among the highlights are whaling ship logs and journals, blacksmith and merchant ledgers, years of diaries from a Westhampton schoolgirl in the 1920s, railroad newsletters, church records, meeting minutes, 90-year-old letters, artist Robert Dash’s sketchbooks, and a wealth of photographs from various eras.

“We bought probably the best digitization equipment on Long Island, an $85,000 system on campus and then we also were able to put together six portable digitization labs, so prior to COVID I sent students out in teams, sent them out two by two — very Biblical,” Dr. Hunter says, explaining how the RDLGF grant helped make the project possible to do work in-house at LIU and on-location at the various historical societies. In Southold for example, two students went with a portable digitization lab, including a scanner, laptop, cables and everything else they needed to do the work without removing a single page from the building.

Dr. Hunter says their equipment makes it possible to scan bound materials, oversized maps and other things that could be harmed on a standard office scanner.

“I think the project is important for several reasons,” Hunter continues. “One, as we sort of say on the website, we’re telling the stories of Long Islanders. That’s what really is exciting to me, the hidden stories that we’re finding every day as we digitize. … We just started doing some church sacramental records from 1725 and on page one there’s the baptism of a slave, so we’re making the stories of Long Islanders accessible. That’s the key.”

And now that all this material is digitized, with hopefully much more to come if their grant is renewed, Dr. Hunter says the possibilities for what to do with it are endless. “You could do what they call a social network analysis. Take these blacksmith ledgers, take the other merchant ledgers — you could link up with computer technology, you could figure out who was dealing with whom, who was buying, who was selling, what were the paths on Long Island where folks were in contact with one another?” he muses, noting that one just needs to search for a “whaling log” to find all related documents in the archive, which you could then compare to get a more accurate picture. “First we’ve tried to build the collection, but the research possibilities for everyone, from computer scientists to someone doing their fourth-grade local history curriculum, it’s all there.”

A major standout in the archive comprises hundreds of photographs from Southampton History Museum, which submitted more than 1,000 negatives from their Bert Morgan Collection. Taken during the 1930s to the 1960s, the black and white images present a never-before-seen record of Southampton’s high society during the era.

“We do not have the budget nor the expertise to digitize any of our collection, and the Bert Morgan Collection came to us catalogued with names and dates and locations, but they were negatives so it would have been impossible for us to even begin to start digitizing over 1,000 images without the Gardiner Foundation and LIU,” Southampton History Museum Executive Director Tom Edmonds says, describing his gratitude for having such a valuable asset brought to life. “The history has been forgotten and this is a great way to document something that happened 70, 80, 90 years ago that has not been recorded in any other way. It captures a lifestyle unique to that period.”

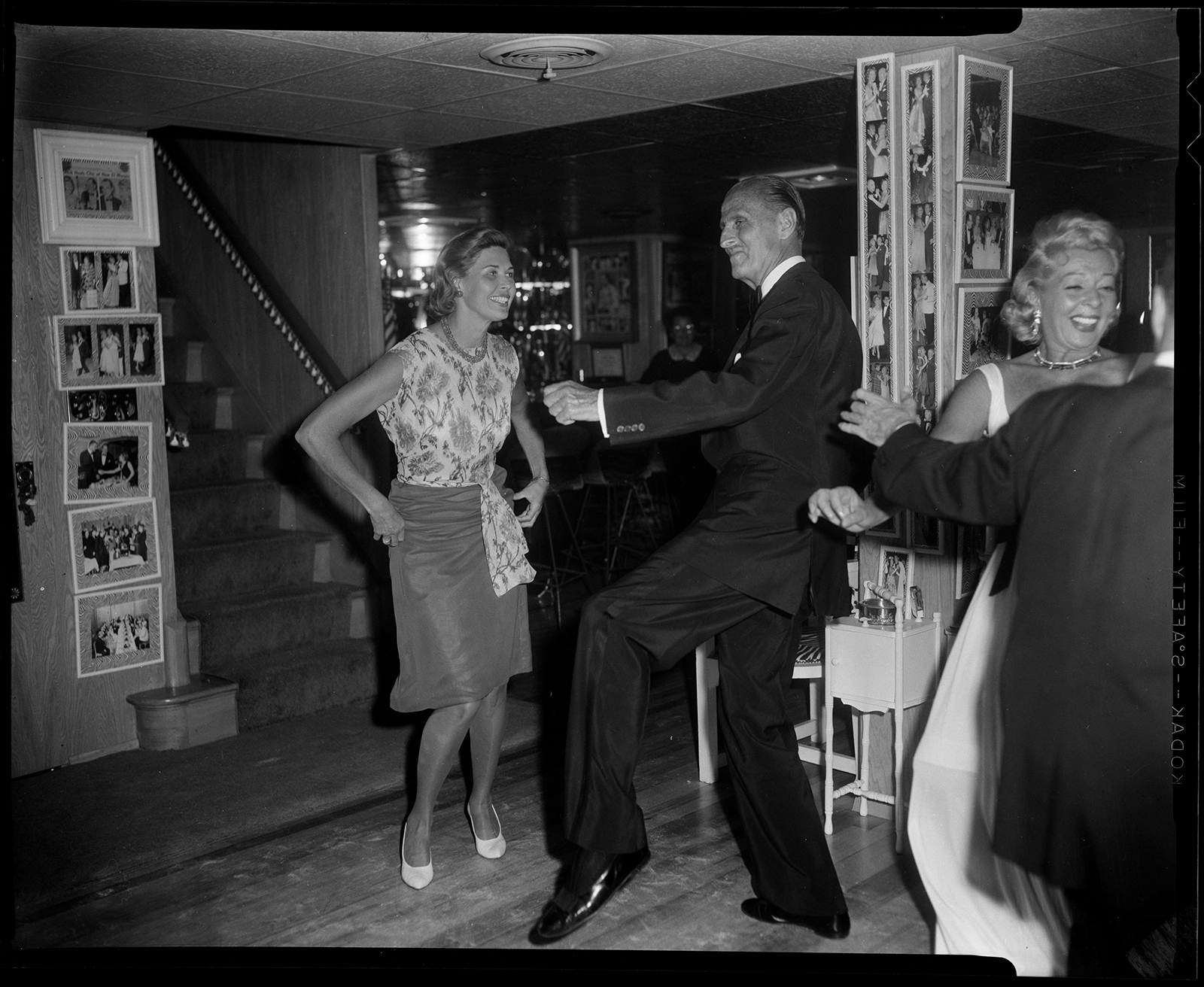

The shots, taken by go-to society photographer of the day Bert Morgan, show Southampton’s wealthiest residents and celebrities at various events and gatherings, playing in the early days of what is now called the playground of the rich and famous.

“What’s coming to light is the history of the Summer Colony. That’s what we call the group of very wealthy New Yorkers who came to Southampton and saved it from tanking. Southampton was a very, very poor agrarian village until 1870, and then rich people moved in and gave everybody jobs and increased the economy, and locals were able to survive because of the wealthy income and the needs they had,” Edmonds explains, adding, “This document … It also puts Southampton on a national scope because a lot of the people who are in the images were celebrities at the time and still are.”

Among the most interesting shots, such as pictures from debutant parties and Henry Ford II’s wedding, are a series of photos taken during a costume party inside a bomb shelter, built as Cold War fears began to take hold in the United States, at the Blue Haven mansion. “They decorated it so it looked like the New York City nightclub El Morocco,” Edmonds says, marveling at the odd images. “They had banquettes and zebra patterns and they had waiters and a fancy bar. .. There are famous people doing the Twist, and making cocktails and they’re just having fun in what looks like El Morocco but it’s actually a bomb shelter on their property.”

Describing one of his favorite photographs, Edmonds points out, “The owner of Blue Haven who built this, during the party he was dressed up like the devil and he’s shaking two different kinds of liquor into a punch bowl. It’s hilarious.”

If the project continues, Edmonds says he’d next like to submit a collection of glass negatives showing local people going out on picnics in the 1890s. “We’ll have both sides of the society here. It’s an amazing project. … All thanks go to the Robert David Lion Gardiner Foundation,” the museum director adds.

“Archivists, folks in my field, we don’t just want to preserve the records of the great white fathers, the political leaders, the Jeffersons, the Madisons,” Dr. Hunter says. “We understand that community history is important, that individual stories of people should be preserved. That everyone should be able to understand their heritage and their neighborhood.”

Dr. Hunter says he’s currently waiting to find out if RDLGF will extend their grant so the project can continue. If given the green light, he will begin taking new applications from historical societies, especially those that may have missed the first opportunity.