Eye on Photography: Jim Lennon and 'The Shoreline' Book

Ask Jim Lennon the key to his success as a commercial and art photographer for over 40 years and the answer is clear: lighting.

Whether capturing a dramatic, giving sky at the beach down the road from his house in Flanders — where he has lived since 1983 — or running a 20-person crew on-location at Jones Beach or Montauk for a national ad campaign, or creating a product shot that makes you go, “I want that now,” Lennon knows the power of lighting.

“Lighting is really understanding and being comfortable in knowing how to use and manipulate lighting and not being afraid to experiment,” says Lennon. “One of the things that I love the most that people will say to me is that they don’t think I light stuff … I light everything. And if I don’t have to light it, it’s because I’ve calculated when I have to be there for the right light.”

Lennon also has a great eye, has learned his craft and paid his dues — exuding an infectious passion for life, the environment, his work and the collaborative process with clients.

“I love my job — I’m not a slave to it, but I’m always working … you set a target, you build it and along the way everybody gets excited about it,” he says.

A self-described “people person” who loves the landscape, Lennon has photographed thousands of people, places and products, both in the studio and on-location. His corporate clients and commercial work range from portrait photography to large advertising campaigns on the regional and national level.

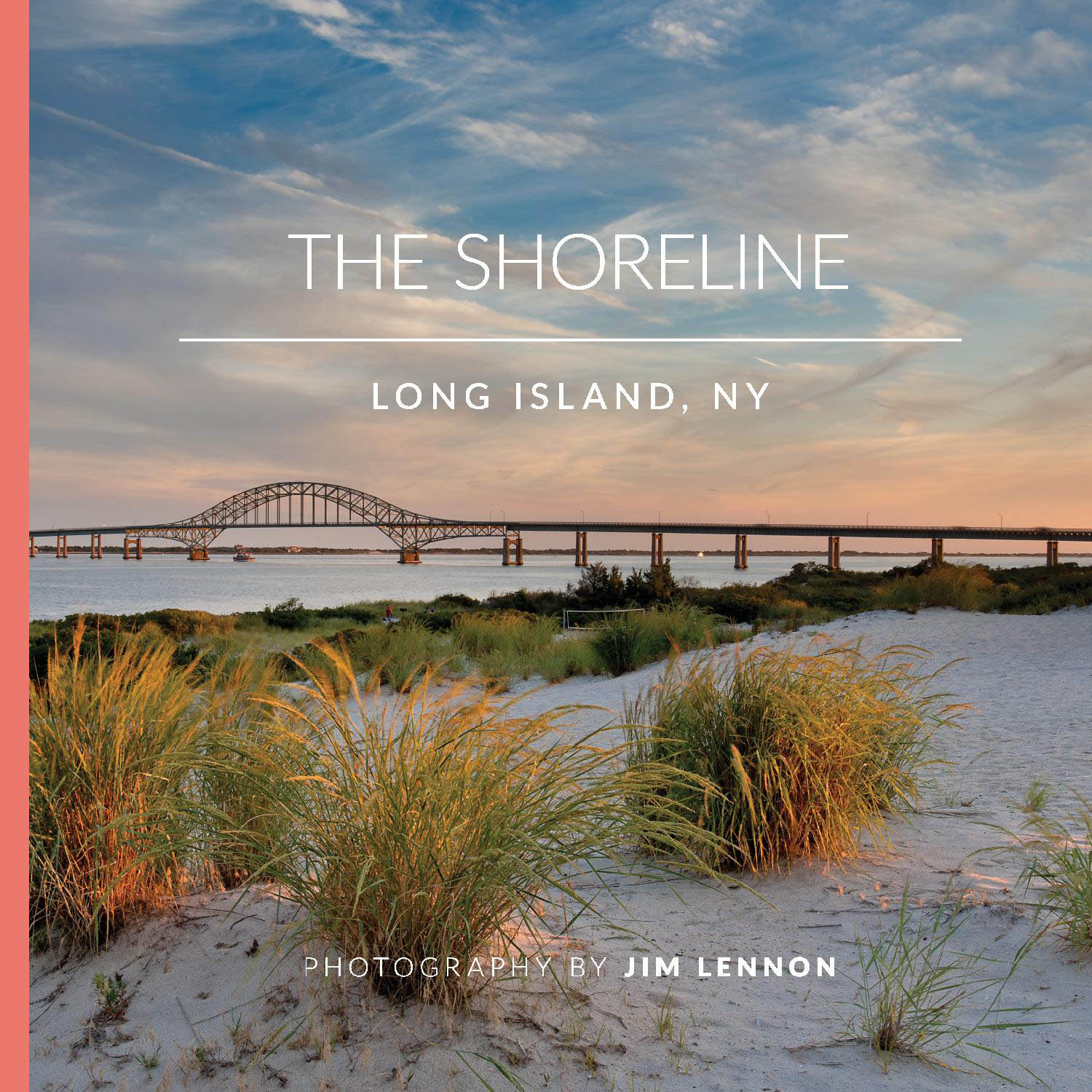

When COVID first hit, he used the unfamiliar downtime to produce a stunning, self-published book of his personal photography titled The Shoreline, featuring 196 pages of coastal scenes he took along the shores from Manhattan to Montauk.

It’s hard to imagine Jim Lennon living too far from any shoreline.

Born in Oceanside, his family came out east when he was young, first to a summer home and then moving to Flanders in 1978. Lennon says he quickly “gravitated to the people out here and the place itself” thanks to newfound friendships that felt more down-to-earth.

“We had water, we had beaches … you were allowed to roam within the size of Rhode Island … horses, mini bikes, go-karts, bows and arrows, rifles — that kind of stuff didn’t even exist in Oceanside,” he adds.

It seems Lennon was always destined to record and preserve the exquisite moments.

“I won a national award from Kodak (for a landscape) in high school in 1975, but who the heck thought you could make a living at this?” says Lennon, who currently works out of a 2,500-square-foot commercial studio in Hauppauge that he refers to as his creative “dream space.” This is now his fifth studio on Long Island.

Lennon still keeps the “fun little Kodak 126 camera” that his dad gave him as a kid in his studio, recalling with fondness the pivotal day when his father introduced him to award-winning Daily News photographer Danny Farrell, famous for his shot of a young John F. Kennedy Jr. saluting at his father’s 1963 funeral.

“After I showed an interest in photography, my dad had Danny take me out on some assignments, and he taught me and gave me a little bit of direction,” Lennon says. Something clicked.

“That’s when I thought, ‘People can make a living at this,’” Lennon recalls, with a smile in his voice. He filed the thought away.

When it came time for college, Lennon did the practical thing — enrolling at Adelphi University to study accounting and business management. Ninety credits in, when it came time to choose an elective class, he naturally picked photography. And the rest clicked, for real, into place.

“I was getting all the answers and the professor said, ‘How does the accounting guy know the answers?’ And I said, ‘I read the book.’ And he said, ‘This is photography, nobody reads the book.’ Then, when the guy running the lab there left, the teacher said to the rest of the (photography) department, ‘I got a guy in my class, we should hire him. He read the book.’ And that was it — there was no turning back. That was the beginning of me working full-time, since 1977, only in photography.”

Lennon worked at Adelphi for three years running the lab (he returned many years later to teach advanced and studio photography there for 17 semesters). After a year and a half stint as the features photographer at The Suffolk Times, he began to take opportunities assisting friends who were established photographers in New York City.

He found himself working on large accounts like Seagram’s and the American Stock Exchange, honing his technical craft as well as “learning by osmosis how to act and what clients expect of you on a job.” It paid off.

“When I got my first big annual report out here through a rep around 1985, the North Fork Bank, it was a $15,000 job, which was big back then,” Lennon says, adding, “I didn’t hesitate, I was ready.”

Today, Jim Lennon seems as busy as he wants to be, between his commercial clients and his personal work. We caught up with him via phone to talk about his craft, his new book and his advice to photographers starting out.

Let’s talk equipment: What do you use?

My cameras are Hasselblad and Nikon digital cameras. I have something around 50 electronic strobes in different configurations — battery, remote-operated studio systems. I have way more lights than I need.

Lighting can intimidate people. Why is it so important?

Lighting is a science. … Everything is about ratios and proportions and once you learn that, then the confidence of knowing what to do with your equipment kind of settles in … and you know how to apply what you are good at. I tell people, “If you are nervous on the job, you’re not ready to be on the job. You don’t want a nervous guy putting the brakes on your car. You don’t want to pull out and the guy says, ‘I’m hoping they work!’”

What is the commercial landscape like these days?

We’ve become such a visual society … pictures get used faster, the new ones sooner and (my clients) need them to look a little better than the person next door. I do a lot of product photography and work for restaurants, and you can have really great food, but if you have crappy photos of great food, it looks like crappy food.

What kinds of jobs are you working on?

This past month we got five new clients — I don’t know how — and the range is from rebranding a whole X-ray company to these wraps that are going to be on soda machines that are going to be across the country. A lot of people I’m working for in this business are turbo-charged to communicate with people, and so they are going to get as much mileage as they can in different mediums and spots and spaces that can actually use visual.

Favorite jobs? What do you love to shoot most?

That’s so hard to say. I love the work that I do all the time, and it’s hard for me not to get excited when my clients get excited. I always love photographing people … it’s all about character. And people don’t get that character is way more impressive than anything else in them. You look at a picture of somebody — whether they’re good looking or not good looking — and you think to yourself, “Man, I would really love to get to know that person.”

Why did you self-publish The Shoreline?

I went to three publishers total, two of them got back to me and said, “Yeah, we’re interested, but here’s what you’ve got to do to change it.” … They wanted more lighthouses, more ducks — and I didn’t want to do that — so I just decided to self-publish it. And there’s nothing in it that I would change.

I decided to focus on just the coastline … I literally did it for myself. I’ve sold 450 framed and plexiglass-mounted prints (of The Shoreline photographs) to clients and commercial people and thought, “What a great way to wrap up a theme … and (create) a vehicle by which other people could see these photographs.”

Favorite spots out east to shoot?

My neighborhood (Flanders) is incredible. I put out whole calendars just on my neighborhood. … The whole East End … it’s just beautiful. Every favorite spot that I’ve ever had is probably the last spot that I really found a great photograph in — and you find them out here.

Advice for someone getting into the business?

Get good before you do anything, and good doesn’t happen in a year. You need to look to and listen to the people that can turn you down, because if they don’t turn you down, then you’ve got something. If they do turn you down, there’s a reason.

A lot of people will just try to do stuff that appeases their friends, builds their ego, gets a lot of likes on Facebook, and if you’re starting out, the first thing you have to do is really go to the people that are going to shut you down if you’re not performing — and you learn fast.

What drives you? What do you love the most about what you do?

I love the landscape. … There are a dozen places in my head that are usually close to wherever I am, and if I see light stuff starting to happen, I know that I’m going to gravitate to one of those places at the end of the day and get something there that’s going to be different.

The thing I really find interesting about it is … you’re a preservationist. You get to record these things that are never going to be in the same place in space or time, in that light again, and you get to preserve them and save them and pass them on.

Jim Lennon will be giving a talk about self-publishing The Shoreline in January at the Alex Ferrone Gallery (25425 Main Road, Cutchogue). To see more of his work, visit jimlennonphotography.com.