The Numbers Are In: It's a Good Time for East End Birders

In his 2005 bestseller, The Big Year: A Tale of Man, Nature and Fowl Obsession, author Mark Obmascik succinctly explains the allure of birdwatching, or “birding” for the more active pursuers of the hobby: “Birding is hunting without killing, preying without punishing and collecting without clogging your home.”

For many, birding is an obsession that takes them to the ends of the earth and back in search of rare species and unique habitats to check off the next box on their list. For others, birdwatching is simply about passively admiring our wondrous avian friends and neighbors at the feeder or on a lovely stroll through the woods.

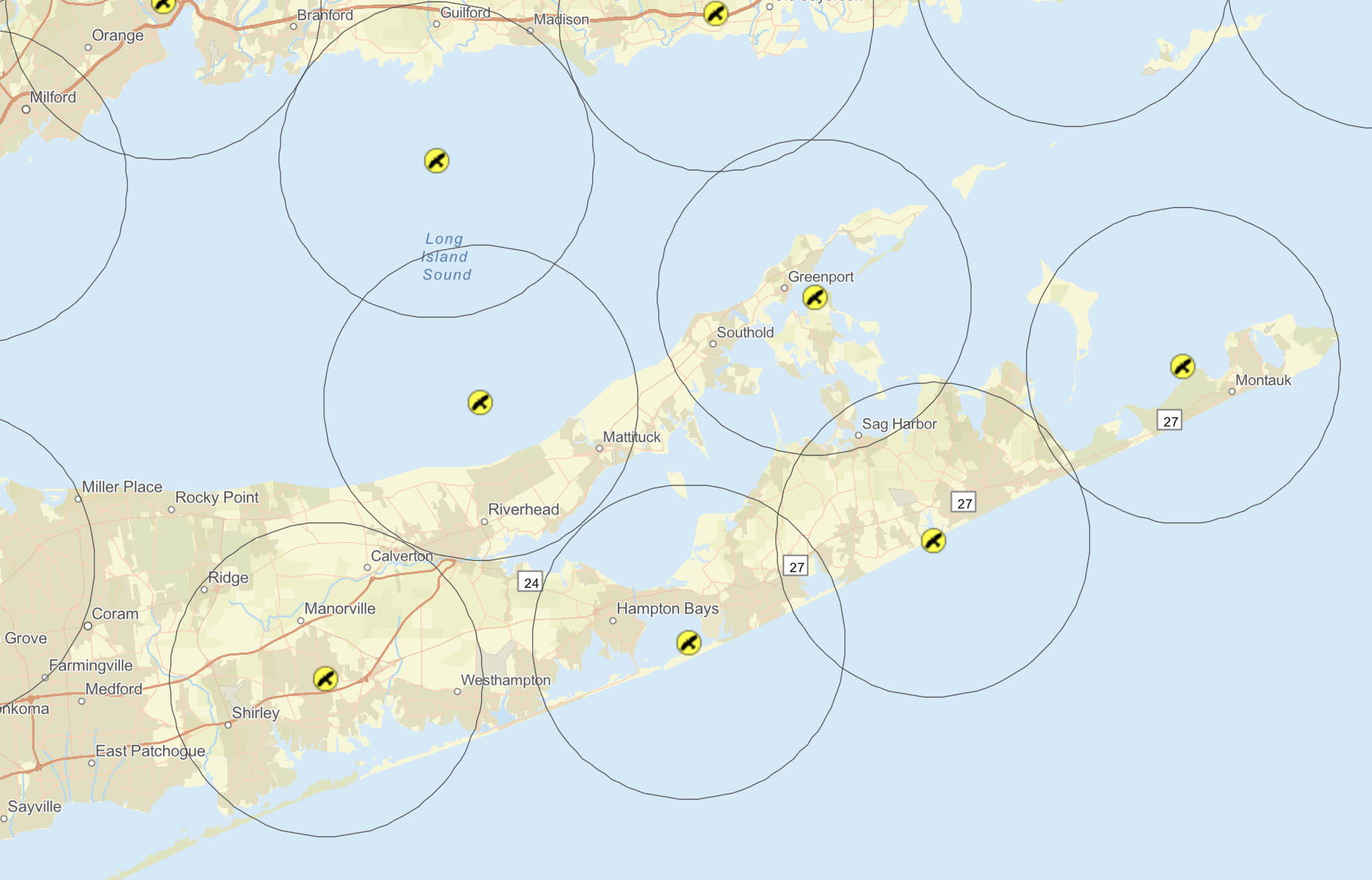

Here on the East End, experienced birders point out that the hobby is growing, especially since pandemic lockdowns kept people at home and folks began seeking things to safely pass the time. But the biggest birding event of the year has to be Audubon’s annual Christmas Bird Count (CBC), a 24-hour effort where dozens of volunteers gather to observe and report on local bird populations, counting each individual species seen and heard, and the number of birds represented within those species. The results are collected from various 15-mile-wide, circular sectors throughout the region, and then compiled to determine the health of particular avian populations.

Eventually, once all the information has been sent in to the Audubon Society, one of the oldest birding organizations of its kind, the data from all sectors can be put together and used to paint an overall picture of our permanent resident birds and those migrating to and from other destinations.

Touted as “one of the longest-running wildlife censuses in the world,” the CBC just completed its 122nd year in December, and some of the local counts go back almost to the beginning.

On the North Fork for example, the Orient CBC took shape in 1904 when a local farmer named Roy Latham began the tradition, and it has continued every year since. “Orient is one of the oldest counts that’s still active,” explained John Sepenoski, a Southold Town GIS engineer, avid birder and current compiler of data for this 15-mile area, which covers Orient and extends west to Peconic. Another count zone, called simply “North Fork,” was added to the west of Orient this year, encompassing a 15-mile circle from Cutchogue to Baiting Hollow.

Sepenoski had not completed his full report from this year’s CBC before press time, but he had enough to say biodiversity was strong in his area. “In Orient we tied the all-time record for number of species recorded,” he says, revealing that they found 121 total species. “I was hoping we would break it, but it didn’t happen,” Sepenoski continues, pointing out that 2021 was the third time Orient had recorded 121 of species, though the variety differs. It would be almost impossible to have all the same species on the list, he explains, so each year is a little different from the ones it tied.

Standout species in Orient this year included a rare blue-headed vireo and the striking Baltimore oriole, Sepenoski says, but this wasn’t the first time the birds have appeared on their count.

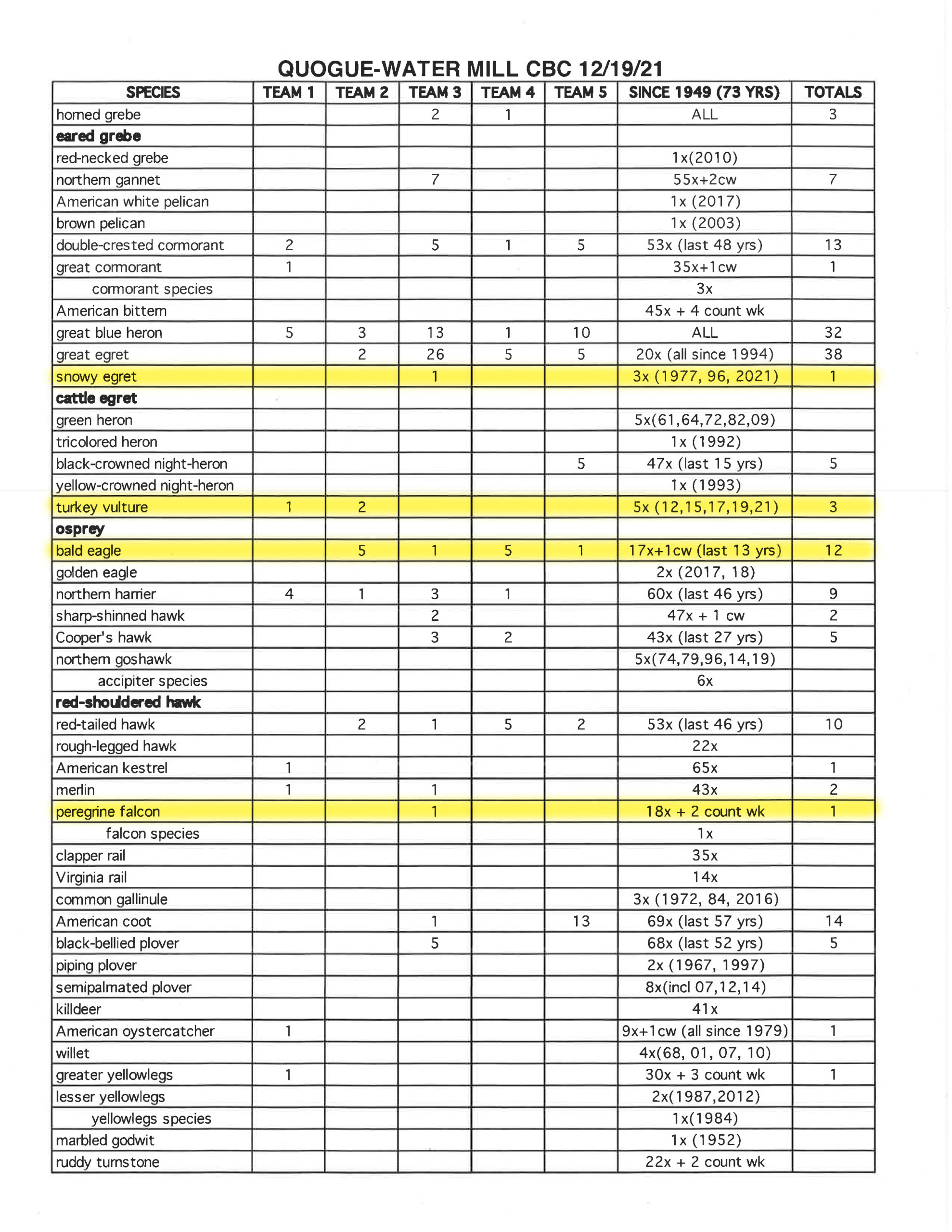

In the Hamptons, Quogue-Water Mill CBC compiler since 2004 and Group for the East End Director of Environmental Education Steven Biasetti’s completed report notes that 28 participants on five teams tallied 107 species and 11,968 individual birds. Biasetti says his particular count dates back to 1949, and the 2021 numbers reflect, for the sixth straight year, the most “distressingly low” number of individual birds since the 1970s, though he acknowledges this small sample area — just a 15-mile-diameter circle — cannot accurately show big-picture problems.

Still, his report notes, “This troubling trend merits sober consideration.”

On the other hand, Biasetti says the Quogue-Water Mill count recorded some exciting and rare birds, including two species that have never before appeared: a pink-footed goose and a clay-colored sparrow. Among other standouts were 12 bald eagles, a snowy egret, one peregrine falcon, three common ravens and three turkey vultures.

“There are half a dozen species that we’re seeing regularly now on this count that we’ve been doing since 1949, that you didn’t see for the first 50 years,” Biasetti says. “That’s the way with nature. There are organisms that benefit from changes in the environment, and there are organisms that decline because of it,” he points out, adding later, “Bald eagles are much more common now, common ravens are more common now, turkey vultures are more common. Wild turkeys were reintroduced in the 1990s, but now they’re all over the place.”

In other words, he says, “There are declines in certain species, and maybe some declines overall in individual birds, but there are some species that are adapting to the eastern Long Island environment and are doing better now than they were 30 years ago.”

This makes it a thrilling time for birdwatchers, especially those who have been around long enough to see the changes. Northville resident and former Orient CBC compiler MaryLaura Lamont, a longtime birder, says she’s seen a lot of changes over nearly 50 years of bird count participation, some upsetting and some encouraging. “When I was a kid in Northport, I never saw bald eagles. Who would have thought I would live to see bald eagles nesting on Long Island,” she marvels. “It is an unbelievable success story for conservation when there aren’t many success stories for conservation.”

Lamont also points to the osprey’s comeback, and to the new populations of turkey vultures. “You never saw turkey vultures 20, 30 years ago, and now we have them on Long Island every day of the year, throughout the entire year,” she says, pointing out that the vultures are now nesting here, just like eagles. “It took eagles decades to come back, but they did, and now they’re nesting all over the place.”

But it’s not all good news. Neotropical birds, such as warblers, verios and thrushes, are decreasing in number and “terns are in severe trouble,” Lamont says, noting that their numbers were once in the thousands. “A lot of birds are now in trouble because of habitat loss. Climate change is certainly affecting birds,” she says, describing how robins used to be harbingers of spring, but now remain here year-round, though their numbers are still robust. The Quogue-Water Mill CBC recorded 473 common robins in December.

With all the changes, big and small, positive and negative, birdwatchers have more than enough to look at on the East End. “There’s great avian diversity on Long Island,” Biasetti says, noting that some 350 bird species can be found on Long Island each year. “It’s a variety of habitats — it’s fresh water and saltwater, it’s bays and oceans and harbors, and fields and woods. You get a good variety of habitats, which then bring a good variety of birds.”

“There are a lot of birdwatching people around. It’s become a very popular sport, or art form if you want to call it that,” Lamont says. “Birds are everywhere, all the time, throughout the year, so it’s something very popular that people like,” she continues, explaining that COVID has brought even more people to the hobby. “A lot of people got into it because you couldn’t go to work, you really couldn’t go out with people socially, so a lot of people started concentrating on looking at the birds in their yard. I’ve been told this by so many new birders, that that’s how they started. They started watching the birds in their yard because they were housebound.”

And the best part, though tools such as binoculars, a notebook and field guides are helpful, all one really needs is a pair of eyes.

Find more info about birdwatching/birding and how to get started at audubon.org.