Taking Down Serenity: Remembering Chief Ralph George

A month after Ralph George retired, I called him up and invited him to have coffee with me at John Papas Café so we could talk about the time he and I took down Serenity. He had a better idea.

“Stop by my house about 10 tomorrow,” he said. “How do you take your coffee?”

“Milk, no sugar,” I said. “But I don’t know where you live.”

He told me. He lived on Springy Banks Road between the cross streets of Soak Hides Road and Three Mile Harbor Road. For his 40 years as chief of the East Hampton Marine Police, he could walk to his police boat every day.

The house was a small ranch affair. His wife met me at the door and led me down to an unfinished basement where George sat in a swivel chair amidst all the accolades, awards and framed photographs that described the arc of his career. A furnace was in the far corner.

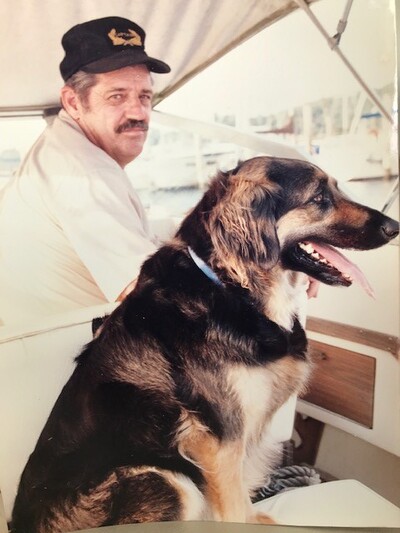

He gave me a tour. There were awards from the police department, photographs of him in his uniform in his little boat with the flashing lights on the roof, of him giving out a ticket, of him shaking hands with millionaires and celebrities.

An old marine radio tuned to the emergency channel squawked on a shelf amidst weather gauges and compasses.

“Anything about the time we took down Serenity?” I asked.

“I have your article about it in a frame,” he said, “but that is it.”

“That was quite a time,” I said.

“The highlight of my career,” he said.

* * *

In 1976, at the age of 37, I bought a house on the side of a hill that looks out across the street to a sunset over boats docked at this inlet on Three Mile Harbor. I still live there. I love this spot. Others do, too. Often, motorists will stop in front of the house to watch the sunset. Nearly 200 yachts and sailboats bob in the slips of four marinas here. What a scene as the sun goes down.

Something I enjoyed doing in those early years at sunset was to take my wife and family in a little boat I kept in one of the slips to one of the four restaurants that sit waterfront 2 miles further along the harbor near to the jetty that leads out into Gardiners Bay. The speed limit for boats in the harbor was 5 miles an hour. My 6-horsepower outboard would push us along for a half hour to dinner. Later, as darkness fell, we’d put on running lights, following the buoys of the sea lane, and motor back home.

It was during one of these trips up the harbor that we met Chief George. He pulled his police boat close and said he was just making sure everyone had a life jacket buckled on, which we all did. The kids, age 3, 5, 12 and 14, enjoyed meeting him.

Late one afternoon in early July, we almost got killed by a twin-engine seaplane coming low over the sea lane. Frighteningly, it set down several hundred yards ahead of us and, still going 50 miles an hour, roared toward us. I swerved out of the lane to get out of its way just in time. And, with our boat rocking badly, watched the seaplane skimming along fast, to turn into our little inlet and disappear amidst the boats there. Soon thereafter, still at dinner, we watched it scoot the other way and noisily take off.

The following Friday afternoon, I watched the same thing happen, but from the safety of our front deck. The seaplane pulled into the inlet and came to a halt just 50 yards offshore from one of the largest yachts parked in a marina on our right. It’s name, “Serenity,” was on the yacht’s side. After a while, a 14-foot tender came chugging slowly out toward the seaplane, the name Serenity on its side. A uniformed man was at the wheel, but as it arrived, he tied up to one of the wing struts and helped a man in a business suit with a briefcase climb down from the cockpit and onto his tender. Then he motored back to Serenity, the yacht. After that, the seaplane turned and roared off.

The next thing I did, from the safety of our house, was to call Captain George of the Marine Patrol.

“I saw him,” George said grimly.

“I think he must do this every Friday,” I said.

“I’m gonna catch him.”

The following Friday, the seaplane again arrived. Watching from the deck as the businessman was being helped into the tender, Captain George appeared, standing at the wheel of his 22-foot police boat with his lights flashing. His boat emerged slowly from behind a ship docked on the other side of the inlet and proceeded to try to catch the seaplane in the act. Instead, the seaplane pilot saw him, and in an instant after the tender was away, turned and, with George only halfway across the inlet, swung around and roared off.

Captain George watched him go. Then he looked up at me and waved. He’d failed. So he turned off his flashing lights and motored back to the marina.

A week later, George was quicker. And this time, he got them. He made the businessman stay in the cockpit with the pilot as he slowly and carefully wrote out his summons. He then wanted the businessman to climb down to the police boat. But the businessman wouldn’t do it. Instead, the pilot came down and as the businessman slunk off in the tender, George gave the pilot quite an earful. And 20 minutes later, George finished. With that, the pilot climbed back up into his cockpit, started the engines, and, as George backed his police boat away, turned that seaplane around and started back up the harbor. But very slowly, because George was following him and the 5-mile-an-hour speed limit is painfully slow for a seaplane.

An hour later, I heard that seaplane off out in Gardiners Bay. He would never be coming back.

And here we were, 40 years later, down in George’s basement office, remembering this story.

“Now wasn’t that a time,” Chief George said.

Last week, I read that Chief George passed away on November 29. He was 92. And I thought to write about this encounter one last time.