Honoring 4 Women Who Changed the Hamptons for the Better

The East End is what it is today because of the incredible contributions made by men and women who envisioned more for their communities and took the steps to make the change they wanted to see. With the spotlight on women this month, we want to honor four Hamptons power women who left this Earth knowing they improved their communities for all who came after them.

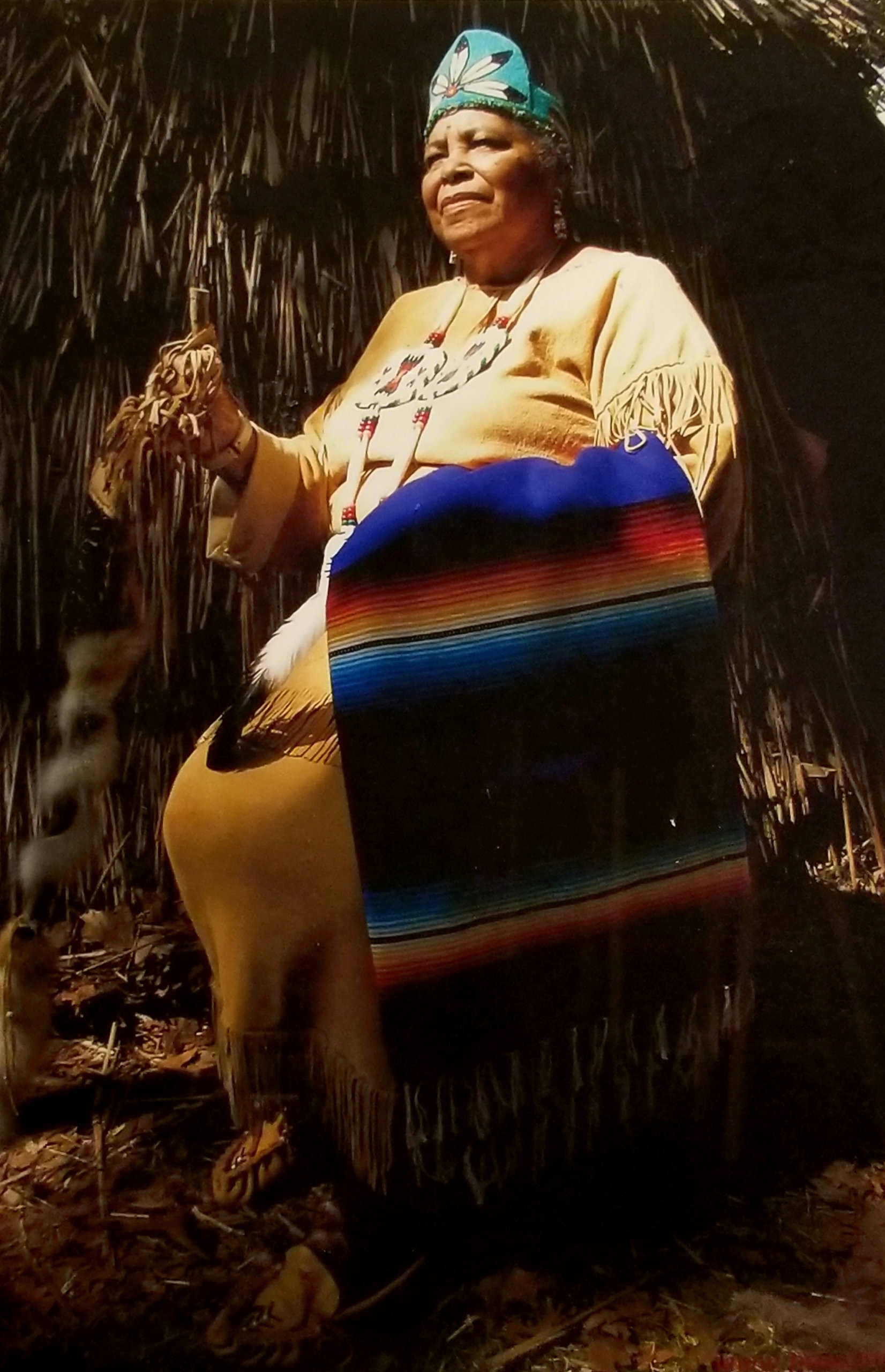

Harriett Gumbs (1921–2020)

Harriett “Princess Starleaf” Gumbs was nothing short of a Shinnecock trailblazer. During her 99-year life, she opened the Shinnecock Nation’s first retail store on Hill Street, Shinnecock Indian Outpost, and was a vocal activist who successfully fought off land claims and petitioned then-President Richard Nixon to add the Shinnecock Nation to federal Indigenous maps. She became the tribal matriarch, a designated princess and the oldest living Shinnecock woman. With a lineage that’s able to be traced back to before the European settlers, Gumbs passed down the stories of her ancestors within the community and in lectures at Ivy League schools.

Courtesy The Athenaeum

May Groot Manson (1859–1917)

Perhaps the most famous of the Hamptons suffragists — due, in part, to the historical marker honoring her at the location of her former East Hampton home — May Groot Manson was chairman of the Executive Committee of the Woman Suffrage League of East Hampton and the Women’s Political Union of Suffolk County. Her home became a hub for frequent suffragist meetings and was also the kick-off point for a 1913 suffrage march she helped organize. She also took part in a cross-island demonstration, carrying the Torch of Liberty from Montauk Lighthouse through the East End before passing it off mid-island to fellow suffragist Louisine Havemeyer.

Amaza Lee Meredith (1895–1984)

Despite being unable to officially train in the architecture profession, on account of being a Black woman in the early 1900s, Amaza Lee Meredith’s talent and passion for it were undeniable. As founder and chair of Virginia State University’s arts department, she was awarded with Virginia’s first land grant to Black scholars and would begin building homes throughout Virginia, Texas and New York. Most notable to the East End are her Sag Harbor projects: Azurest South, a home she built for herself and her life partner Dr. Edna Meade Colson, and Azurest North, a village subdivision that she envisioned as a vacation destination for middle class Black families that has since grown into the Sag Harbor Hills, Azurest and Ninevah Beach Subdivisions Historic District (SANS). Meredith continued to develop designs for buildings, inventions and paints well into her senior years.

Giorgina Reid (1908–2001)

Those who recognize the Montauk Lighthouse as an East End icon should also recognize the woman who saved it: Giorgina Reid. A textile designer living in Rocky Point, she once had to save her cottage from inevitable collapse by constructing terraces in the bluff’s gullies. The Montauk Lighthouse was in a similarly dire situation but on a much larger scale. With erosion shearing a couple feet off the cliff each year, the lighthouse was getting dangerously close to the edge. The U.S. Coast Guard was ordered to abandon it, until Reid proposed her idea to Dan Rattiner, who had been covering the story and advocating for those in charge to find an alternative solution, and then to the Coast Guard. She and her volunteers used her patented process, reed-trench terracing, to build terrace platforms made of beach debris and other materials. She kept coming back almost weekly for 15 years, protecting more and more of the cliff face from erosion each day. Then-President Ronald Reagan praised her heroic efforts, and the Coast Guard promised to maintain her work after she retired.