Techspressionism: A New Art Movement Comes to Southampton

Young and emerging artists often dream big. They share ideas and hope to one day establish a groundbreaking group or movement in the grand tradition of their forebears, be it Cubism and the European avant-garde at the 1913 Armory Show, the Dada manifestos that established a whole new way of thinking about art, the Abstract Expressionists at Cedar Tavern, or the proliferation of Pop and, later, street art. Few of these dreams amount to much as the dreamers fumble for a cohesive, culturally significant hook on which to hang their proverbial hat — let alone an educated, well-connected champion to push their ideas onto the world stage, as Clement Greenberg did for Jackson Pollock and his ilk. With all this said, Southampton Arts Center’s latest exhibition, Techspressionism – Digital & Beyond (open April 21 to July 23) presents a new, locally founded art movement that has about as good a chance as any to become part of the historical lexicon. They even have a well-respected art scholar and critic in their corner.

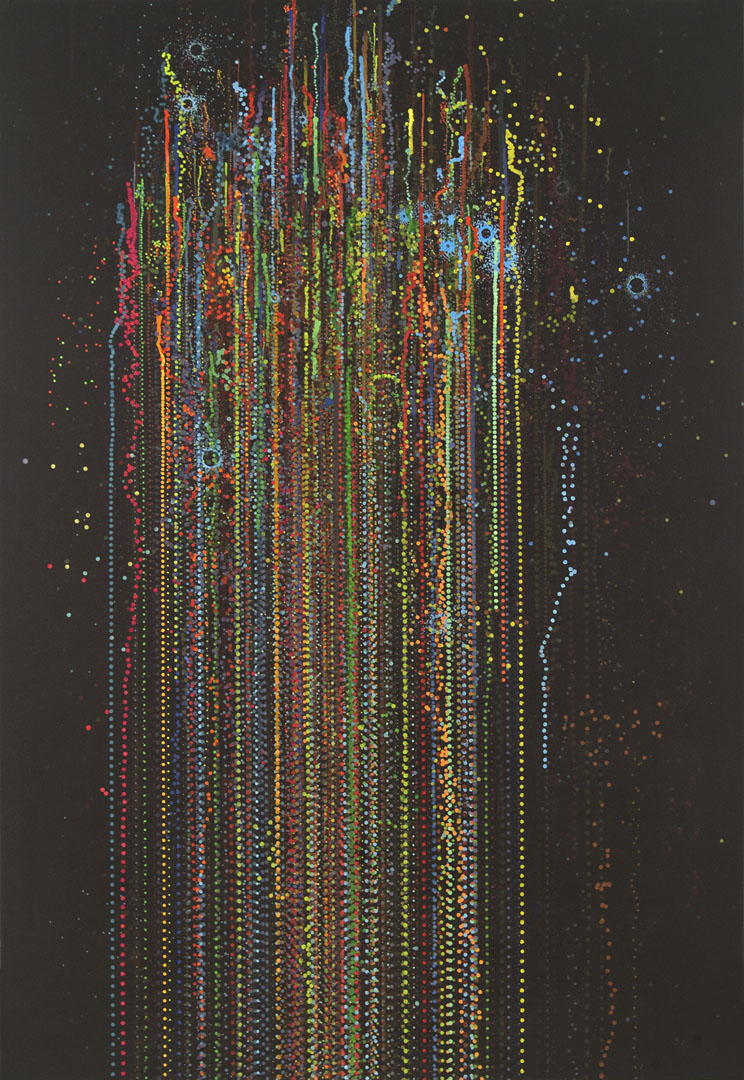

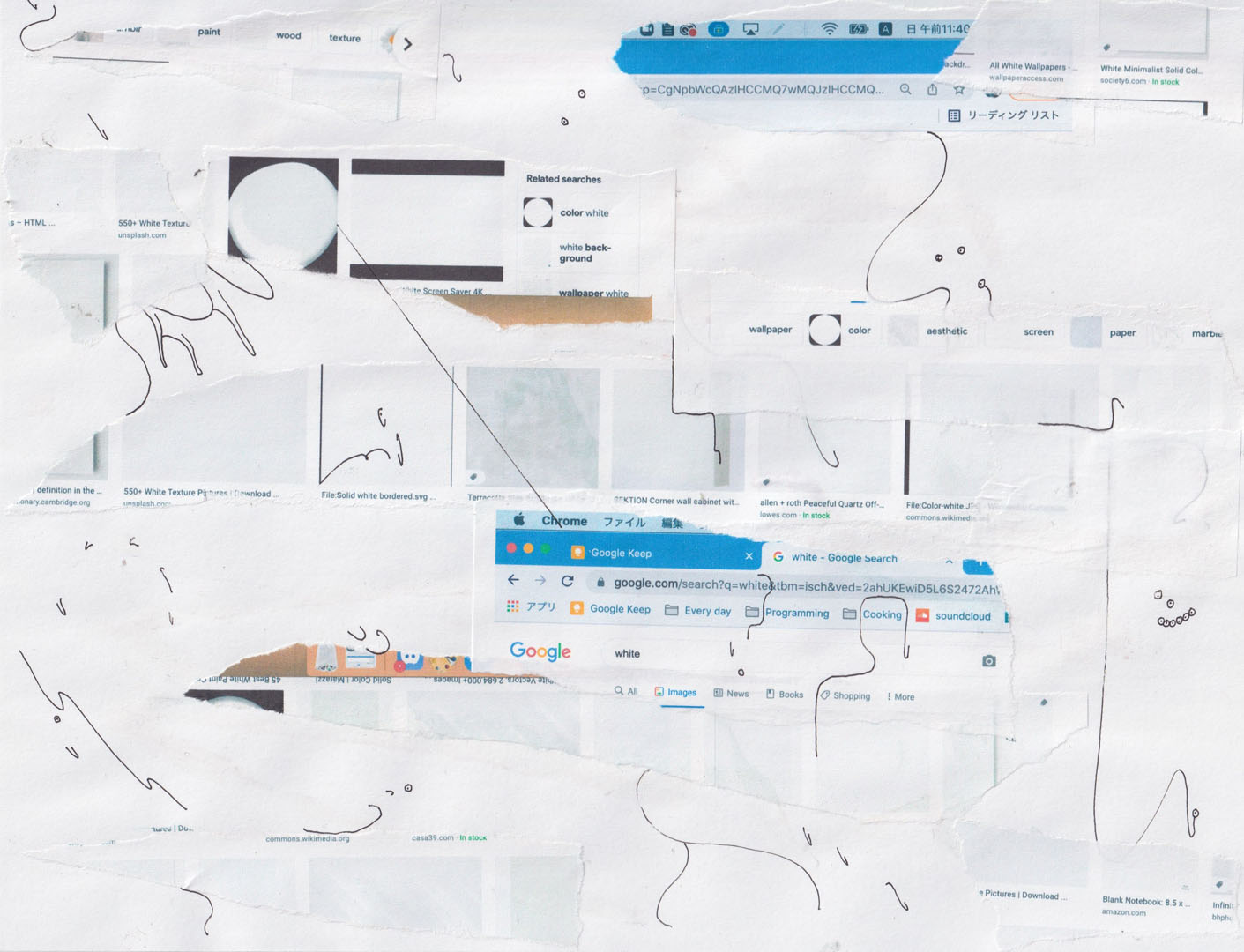

Southampton native Colin Goldberg, the show’s curator and artist who first coined the term, defines Techspressionism (/tek-spresh-uh-niz-uh m/) as “an artistic approach in which technology is utilized as a means to express emotional experience,” and a “21st century artistic and social movement.”

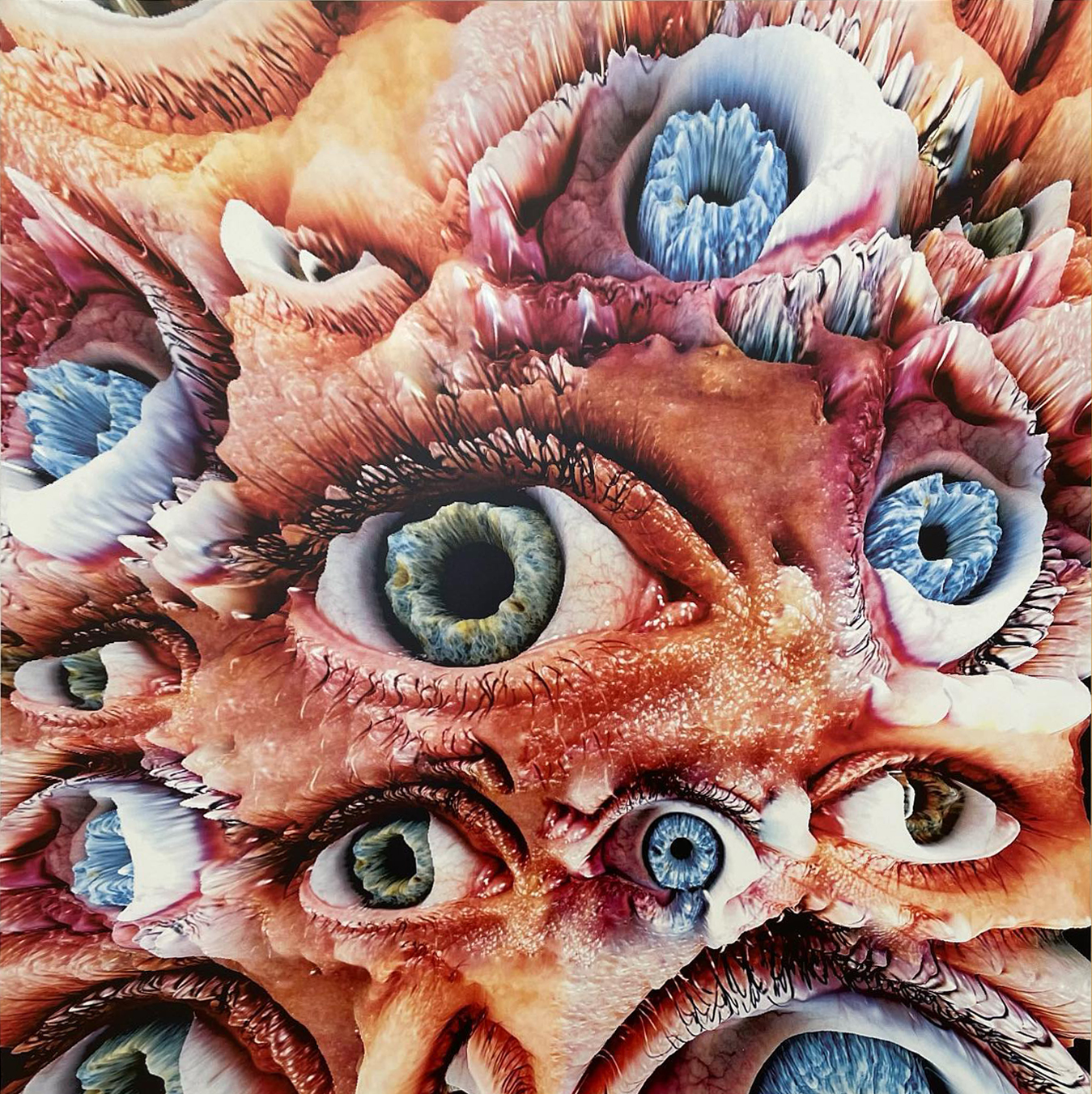

The definition is quite broad, and certainly open to ample interpretation, which can be seen through the wide range of works on view at SAC. Techspressionism includes pieces created in a multitude of styles and techniques by more than 90 artists from more than 20 countries — all united under the banner of technology in its many forms.

“The word Techspressionism was something I came up with just as a title for a show that I did at 4 North Main Gallery (now MM Fine Art) in Southampton,” Goldberg explains, pointing out that he asked art historian, critic and Pollock-Krasner House director Helen Harrison to write an essay for that 2011 solo show’s catalogue. Inspired by the ideas Goldberg evinced, Harrison later became a champion of the movement, an advisor for the SAC Techspressionism exhibition and, perhaps when looking back, the Greenberg to his Pollock.

“I feel like her voice is actually what gives this validity, not mine. I’m just an artist who came up with this portmanteau that’s clever,” Goldberg says of Harrison, who has been part of the effort, which now includes numerous other artists who meet in virtual salons to critique one another’s work, explore different topics and discuss Techspressionism as a philosophy. “She has the art historical knowledge I don’t have to make those connections between what we’re doing and what’s been done in the past,” he adds.

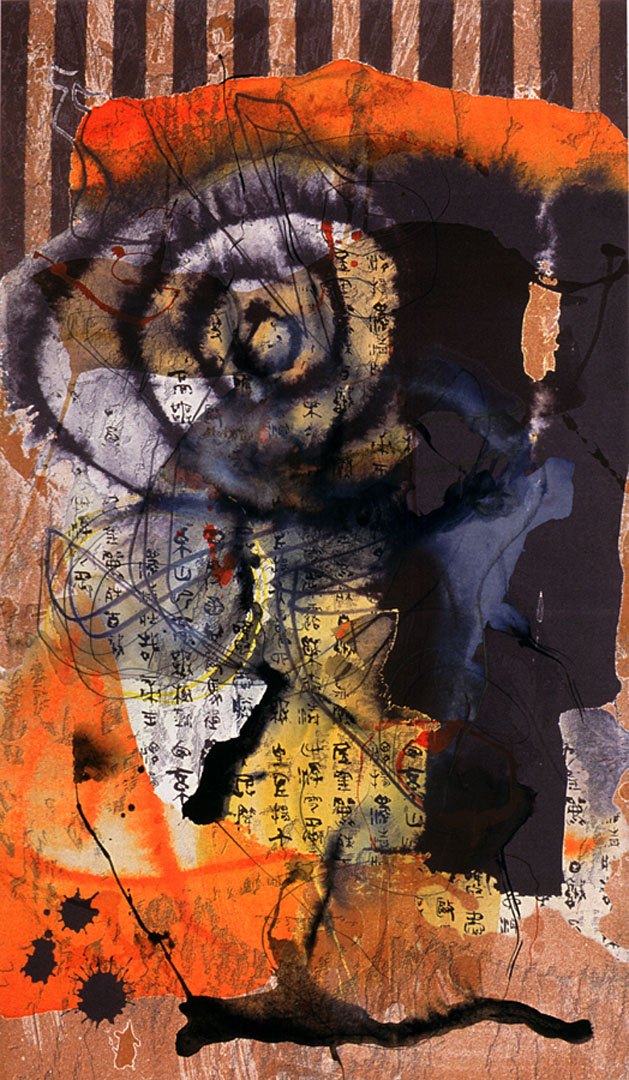

Goldberg has become recognized for his works on paper, canvas and wood, usually layering expressionist painting done by hand with computer-generated wireframes or line drawings printed on top, though he’s also recently dipped his toe into the world of purely digital NFTs (non-fungible tokens) — pieces of art, or any non-interchangeable unit of data, stored on a blockchain that can be bought and sold to collectors. NFTs will be available through the SAC exhibition, but the focus is on the tangible, and it offers photographic works, collage, fabric pieces and X-ray imaging, as well as a full-fledged installation between rooms.

The many styles and media that fall under Techspressionism could seem like something of a free-for-all, but there is a cohesive thread woven throughout. And it is decidedly not about the look or style of the work.

In fact, Harrison made a very important change to the original definition of Techspressionism to explain exactly that. Goldberg’s first definition called it “an artistic style in which technology is utilized as a means to express emotional experience, as opposed to external reality.” The words “as opposed to external reality” were the first to go, but Harrison also noted astutely that the word “style” should be swapped for “approach.”

Goldberg says adding “approach” in place of “style” makes the point that this is not about a bunch of work that has to look the same. “It’s more like a philosophical way to think about using technology, and I think that was really important, that change.”

As Harrison explains it, Techspressionism “may not be an NFT, it could just be a print or something that has a solid form. It could be a video or something that’s projected, or it could even be a three-dimensional piece. … So, there’s kind of a wide range of outcomes or results from using various modern technologies.”

She notes that Goldberg asked for her input in 2011 because he felt a kinship with Pollock and his use of unusual materials, like house paint. “People think Pollock used house paint because it was cheap and he was poor, and of course that is a gross oversimplification, and it also doesn’t have to be true,” Harrison says. “He used it because it gave him the results he was after, and that was the point, that Colin was using technology because it gave him the results he was looking for, and not just because it was some technological innovation that was an end in itself. It was a means to an end,” she continues, describing the crux of this show, which is about applying technology to achieve an image that could not be produced by other means.

“I found that an easy connection, because I felt there was a certain kinship there, so I wrote the essay for his exhibition brochure, and that’s how I got involved,” Harrison says, adding later, “Artists are embracing new technology, because look what you can do with it. But if you just use it for its own sake, it’s boring. It has to have the juice. It has to have the artist’s creative impetus behind it. The more artists use it, the juicier it will get.”

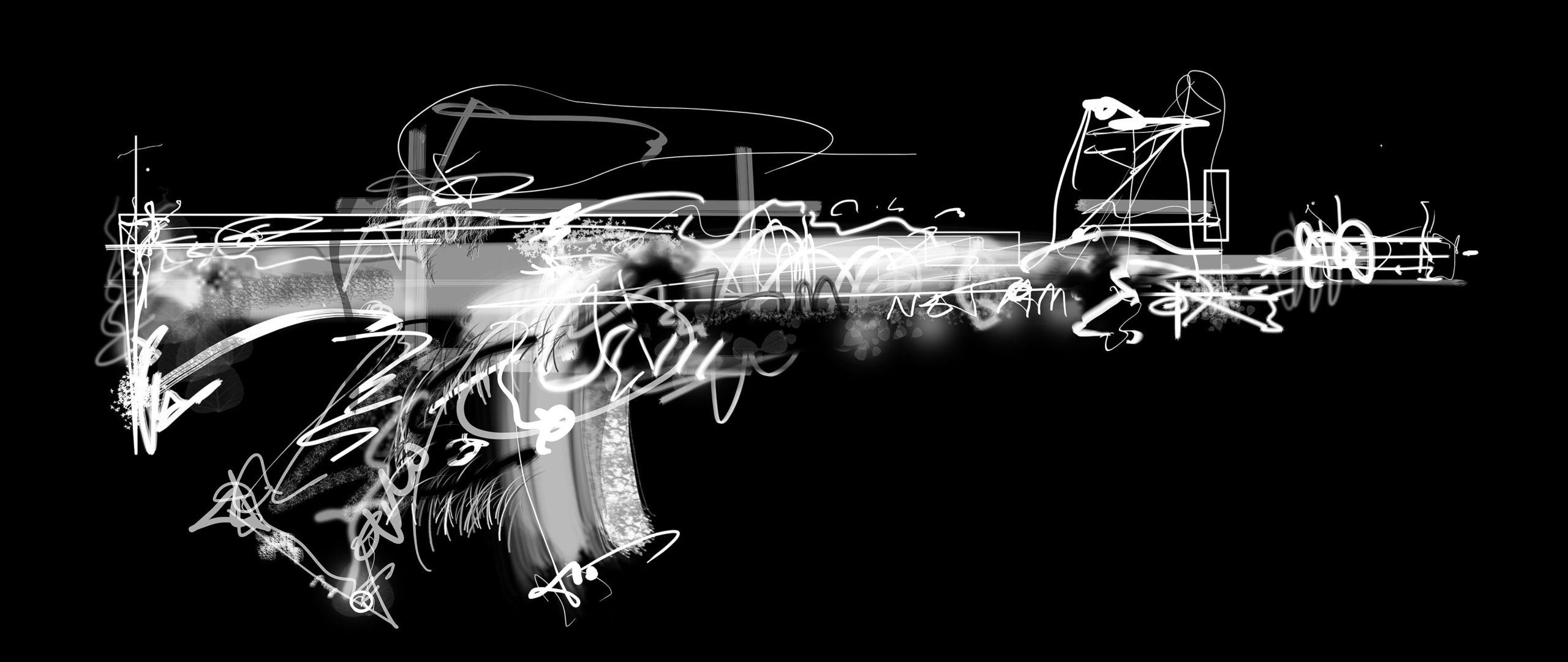

Techspressionism began to proliferate as the ideas further crystalized for Goldberg and others in their growing community, including his friend from graduate school Patrick Lichty — who also felt strongly that the school’s “computer art” (and later “digital art”) program title did not define what they do. Among dozens of artists in the exhibition, plenty of locals are taking part, such as Sagaponack’s Steve Miller — who Goldberg calls the “Godfather of Techspressionism” for his longtime use of X-rays and other innovations in his paintings —as well as Southampton artists Oz Van Rosen, John Zieman and Carol Hunt, Shelter Island’s Roz Dimon (who made a large Kalashnikov rifle image, with all proceeds going to United Help Ukraine), Amagansett installation artist Christine Sciulli, Roy Nicholson of Sag Harbor, East Hampton’s Frank Gillette and others.

To help spread the word, and literally the word, Goldberg launched a website and began poring through Instagram, tagging artists’ images as #techspressionism and inviting them to be part of what they were doing. “People picked up on it and started using (#techspressionism) on their own, and now we’re close to 40,000 posts from people all over the world using the hashtag,” he says. “Based on that, I’ve put together this artists index on techspressionism.com that has 270–280 artists from maybe 40 different countries now.”

Goldberg personally messaged every single artist and asked if they wanted to be in the index, which led to much of the international talent sending work to SAC from countries including Afghanistan, Australia, Belgium, Brazil, Canada, Canary Islands, Czech Republic, France, Germany, Hong Kong, India, Iran, Italy, Netherlands, Peru, Puerto Rico, Russia, Taiwan, Turkey, Uganda, Ukraine and, of course, the United States.

Adding to this building momentum, Goldberg says as recently as this week, Techspressionism community “nodes” have popped up, creating hubs in other countries, such as Iran, Germany, Canada and France — and the French artists are now working on curating their own international show about the movement.

It’s quite possible this exhibition at Southampton Arts Center will go down as a defining moment for an important global art movement. It’s also possible Techspressionism turns out to be a fun, thought-provoking show that remains local. But some smart people are betting on the former.

“Techspressionism will give us greater insight into how these artists use technology as a means of creative expression, whether it be works created with 3D printers, animation, or other digital mediums,” SAC executive director Tom Dunn says of the show. “As a community-focused organization, SAC is thrilled to offer an exhibition like this where we can all learn more about something that is becoming part of our everyday lives.”

Goldberg says people regularly ask if he’s trademarked the word or created a non-profit around it, to which he responds, “No, no, no, I don’t want to do any of those things. My mission is for it to be brought into common usage as a word.” He points out that Techspressionism is now in the Urban Dictionary, and he’s hoping it has a Wikipedia presence in due course. “The more people use it as a word, the more likely it’ll be that it gets brought into common usage,” Goldberg says. “The alternative is it becomes another collective… I don’t want it to be that.”

Harrison says Techspressionism is already making its mark around the world, even if people might not know the word for it. “People all over the globe have connected to this in such an enthusiastic way. I keep teasing Colin about ‘be careful what you wish for,’ because it’s gone well beyond any limitation that he would put on it,” she adds. “There are people in countries you wouldn’t have thought even heard of this, but as soon as they do hear of it, they identify with it, and say, ‘Yes, those are my people.’”

An opening reception for Techspressionism is scheduled for Saturday, April 23 from 6–8 p.m. Visit southamptonartscenter.org/techspressionism for a complete list of artists, nodes, related events and a trove of information that’s worth exploring.