Temik: Hamptons Farming, Labor Camps & Pesticides in Our Water

This past Saturday, June 11, I went to a lecture given by a lawyer named Mark A. Torres about his new book Long Island Migrant Labor Camps: Dust for Blood. He spoke at the First Baptist Church of Bridgehampton.

Potato farming has been going on for centuries here. And farm families could handle it. But by 1940, the potato industry had become so large that potato farming was the dominant industry on eastern Long Island. There were more than 70,000 acres of potato farms and 1,000 farmers on Long Island by the late 1940s.

In some years, the farmers produced, packed and shipped an incredible 20 million bushels of potatoes to wholesalers and retailers everywhere. Turned out the only way to handle this was to send local school buses south to bring thousands of Black migrant workers north in August and September to pick the crops.

I was a teenager when my dad moved our family out here in the 1950s. The potato fields were beautiful green carpets all the way to the horizon in almost every direction. Meanwhile, sometimes on Sundays, I saw Black migrant workers in their dirty clothes lounging around on Main Street in Bridgehampton – a town completely surrounded by potato farms – enjoying the sunshine on the one day they didn’t have to work. They’d sip from small paper bags containing open bottles of Thunderbird wine. I knew they had to be the farmhands. Part of the scene.

What I did not know was that migrants were paid wages subsequently clawed back by the farmers for food, liquor and rent. The rent was for beds in camps on the farms, substandard barracks without running water, electricity or privacy. I also did not know that a few years earlier, a kerosene-fueled fire at one of these camps in Bridgehampton killed two children because that day, the mothers, normally tending their children while their men worked, had been called out – the picking was going too slow – and so had to leave the children to themselves.

In his lecture, Mr. Torres told of fires and deaths in still other camps on other days. There were over a hundred such camps and no housing rules regulated them.

Where Torres spoke, in that church on Sag Harbor Turnpike, many who came to listen were elders now who lived nearby, the children or grandchildren of these migrants. After the lecture, there was a Q and A, and some in the audience spoke, proudly noting they had persevered and in recent years things had dramatically improved. But they needed to embrace their heritage. Like it or not.

After that fire in 1949, the local farm community, shocked at what happened, vowed to never let that happen again. As a group, they bought a 6-acre farm on the turnpike and gave it to the Black community so that during heavy workloads on the farm, the children could go to a safe place to be cared for by others. That has become the Bridgehampton Child Care and Recreational Center today.

Today, the potato farming industry is not the major crop it once was. It takes up only a few thousand acres, and there’s now no need for migrant workers. The camps were razed. It’s over.

However, I believe this dramatic decline might have been inadvertently hastened by an article published in Dan’s Papers back then.

THE STORY OF TEMIK

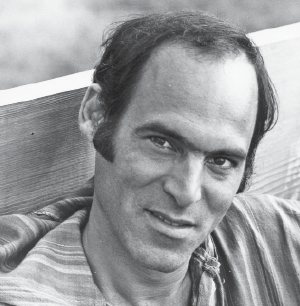

I had befriended a young man named Martin Shepard in 1975. A one-time psychiatrist from New York, he now earned his living buying lots adjacent to potato farms and building modern homes on them. One day, in the fall 1978, he said he’d like to write an article for Dan’s Papers.

“Give me a topic,” he said.

I had rented a small oceanfront house on Sandune Court in Sagaponack that year. Across the street, Shepard had built a modern home alongside a potato field and was now living in it while it was up for sale.

“You know I studied architecture in grad school,” I told him. “Never became an architect, but I remember we studied a city planning project adjacent to a farm field. The professor told us it should not be put there. Farmers spray crops. I wonder if the water at your house is pure. Ask the county to test your drinking water. Write about it.”

At that time, the potato farmers were experiencing the loss of much of their crops to an infestation of nematode bugs. However, they were now spraying a new miracle chemical called Temik on their fields. Its poisons were, according to Union Carbide Corporation, its maker, biodegradable. And it was a big success at eradicating nematodes.

A month later, Shepard called to tell me there was no story here. His drinking water passed.

But I was suspicious. “What did they test for?”

He told me. Arsenic, lead, mercury.

“That’s industrial stuff. Aren’t they testing for pesticides?”

The county test had cost $50 and he had spent that. For a pesticides test they referred him to a private firm, which would require $200.

We decided that since it was his property but my story, we’d split the cost. Turned out that Temik, not biodegraded, was still in his drinking water. We told the county about it, urging them to test elsewhere. And they did.

On August 9, 1979, Marty’s article appeared in Dan’s Papers. Headline was “What’s in the Water?” It created a sensation. A month later, the county announced that tests of over 8,000 wells found Aldicarb, a poison in Temik, not biodegrading, in 13.5% of them.

Temik was immediately banned. And Union Carbide, financially reeling, was required to provide bottled drinking water for thousands of homes for years. The nematode infestation roared back.

And so, potato farming, now only marginally profitable, began an even more precipitous decline. Taxes, linked to land values, soared, and farmers couldn’t pay them. Developers came in. Farm equipment auctions were held. Farm families left. As for back taxes, a new law was passed allowing real estate development rights to be sold to the county. Farm taxes became affordable. Most farming today is for vegetables and grapes.

Around 1990, I watched a young man loading bundles of Dan’s Papers into our delivery trucks for free distribution in nearby stores wearing an old Temik baseball cap. I offered him $50 for it. But he refused.

I have very mixed emotions about all this. Glad at some of it. Horrified at other parts of it, to this day, even in this church.