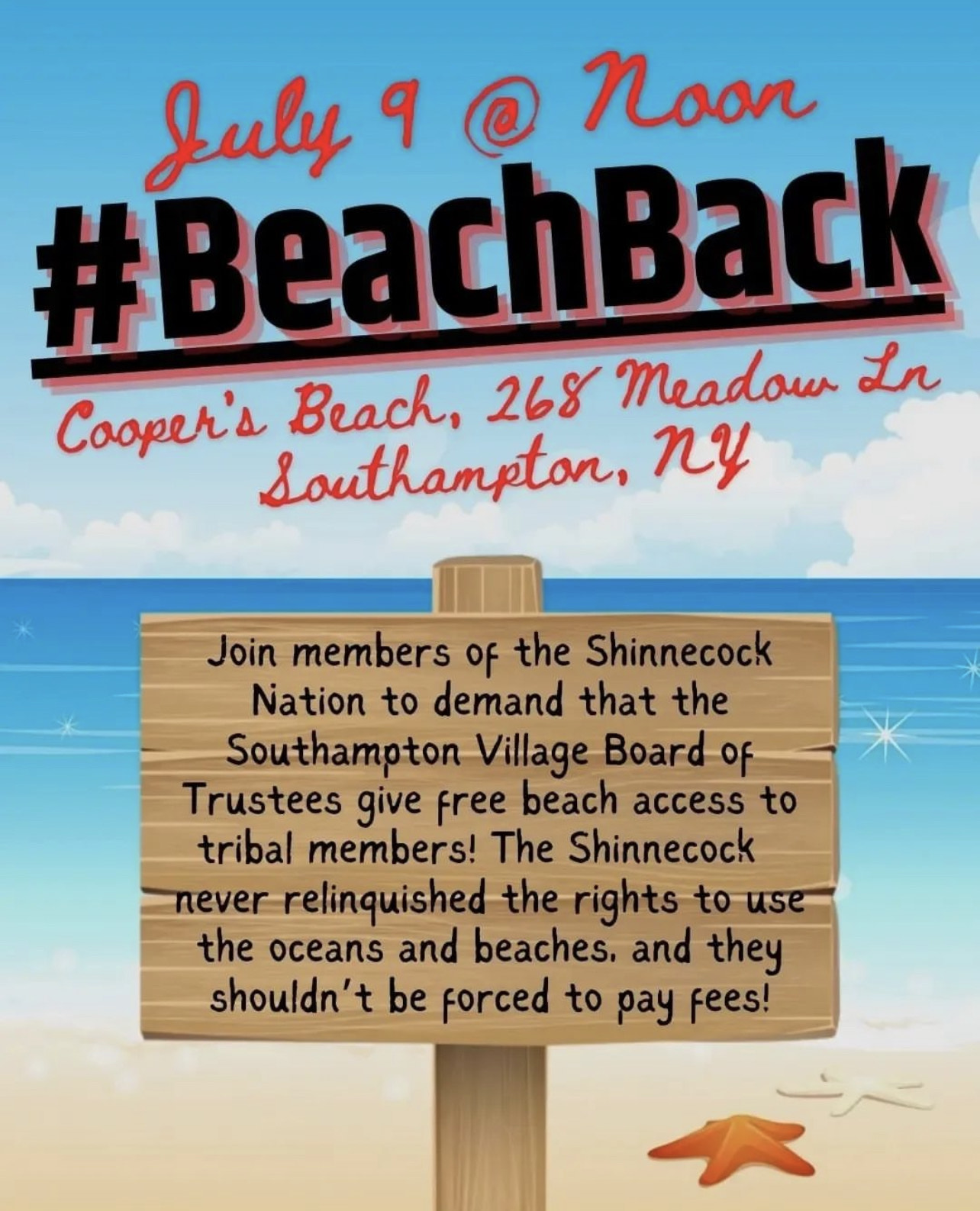

Shinnecock Voices: Join the Nation's Fight for Beach Access

On July 9, members and allies of the Shinnecock Nation will gather at Coopers Beach to protest. The Shinnecock Nation resides on the same territory as our ancestors and lived there thousands of years before us. Despite this fact, any tribal member who lives on the reservation would have to pay the $400 that non-residents must pay in order to access the beach for the season. The village perimeter that grants free beach access conveniently ends before the reservation territory begins. Although the Shinnecock have resided here since time immemorial, respect has rarely been granted for where we reside.

The village of Southampton was founded in 1640 and incorporated in 1894. While both time frames ushered in a period of growth for the village, they were times of great loss for the Shinnecock Nation. It is a loss whose impact still reverberates through the tribe today.

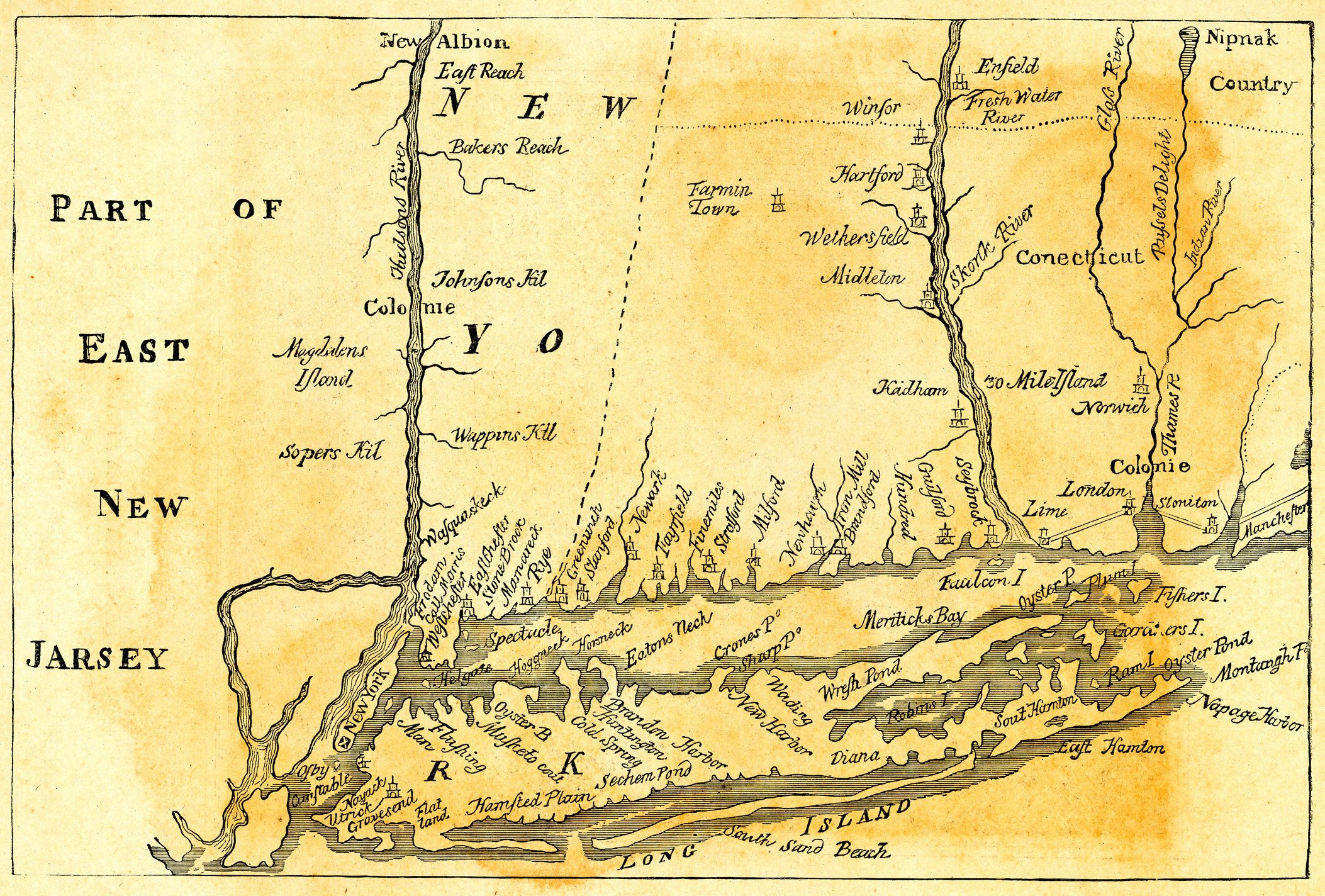

To understand where we are, it’s important to understand the historical context that brought us to this point. Long before mansions lined Billionaires’ Lane, the original inhabitants of the island already had summer beach houses that sprinkled the southern shore. Clans and bands would move from side to side with a gentle understanding of whose territory was who’s. This leisurely relationship to the land was brought to an abrupt stop with the arrival of two distinct groups that colonized Long Island.

The Earl of Stirling was granted a patent and given the island from King Charles I of England in 1636, becoming the island’s first owner. He represented one faction of the island’s colonization, while the Walloons represented the other. Erroneously cited as Dutch, the Walloons were a religious minority subset who fled persecution from a Catholic-controlled Belgium. Many found refuge in the Netherlands and eagerly joined voyages to the New World, setting sail from Holland to Long Island, Manhattan, the Hudson River Valley and other parts of New York.

The distinction between these two cultures is vital because, while neither demographic saw the Indigenous population as equals, efforts were made by the New Netherland transplants to form legal deeds with the Native population. Often, these transactions took place with tribal members who were not equipped to sign the land away. However, these strategies were a stark contrast to those of the Earl of Stirling, whose tactics were to completely dismiss any claim by Native or Netherland communities that lived on the Island.

The earl would approach lands that were already settled by either the Dutch or Natives, and claim them in the name of King Charles I. He convinced British investment bankers from Lynn, Massachusetts that property on the island was most desirable, despite swaths of the land being undeveloped. Those who purchased land on the East End were not doing it for religious freedoms but rather investment opportunities.

While the Dutch and Walloons colonists tried to maintain a less intrusive relationship with the Indigenous population, such cannot be said for their leaders. Director of New Netherland Willem Kieft’s terrible leadership resulted in a war against the Lenape and Wappinger that was so brutal, the Dutch and Walloon population fled in disgust at the massacres of the Indian population.

Peter Stuyvesant, who was governor of New Netherlands when the city fell, was forewarned by female sachem of the Shinnecock Quashawam of the planned attack by the British. His superiority complex caused him to dismiss her. Had he listened to her, instead of referring to her as a ranting squaw woman, the fate of the Big Apple could have played out differently.

Stories of colonial history have often been one-sided. The perspective of the Natives has often been omitted, but when added to the canvas, it paints a much fuller picture of the stories that have been told. If we paint the first settlers of Southampton as English Puritans instead of investors looking to put money in the New World, we have a different connotation of their intentions. Similarly, when the village was incorporated in 1894, its incorporation was able to occur through nefarious means.

With the boom of the Industrial Revolution, wealthy New Yorkers were looking for an escape from the city and found the answer they were looking for in the East End. However, a lease finalized by the English and the Shinnecock in the early 18th century gave the Shinnecock a 1,000-year lease on 3,600 acres in Southampton and prevented further non-native expansion.

After so much land had been taken from Native populations by questionable means, the Non-Intercourse Act passed by Congress attempted to regulate those sales by more official means. The act made it illegal to transfer aboriginal lands without the approval of the federal government. When the wealthy class of New York saw this stalemate, they asked the tribe if they were willing to sell the land. The tribe refused.

Undeterred, the bankers spearheading this initiative went to Shinnecock graves and wrote down the names of our dead on a false deed. They presented this to the New York legislature, which then granted the town rights to the Shinnecock land. However, under the Non-Intercourse Act, such transactions were illegal.

The New York legislation had no authority to make such a deal. Yet the deal was made, and the Shinnecock reside on the territory that was a result of that transaction. We fought, and were denied at every juncture. When we say that Southampton is on stolen land, it is not hyperbole.

Now, 168 years after the modification of the Non-Intercourse Act in 1834, the Nation that has remained continues to fight for the land and waters of which we have always been stewards. Join the Shinnecock Nation on July 9 at Coopers Beach, at 268 Meadow Lane at noon to enable Shinnecock members to have access to village beaches. After the caustic and racist tactics that brought us here, access to village beaches is the bare minimum that can be done to initiate a healing process that is long overdue.

Andrina Smith is a storyteller, writer and performer whose work frequently explores race and the ways we can increase Shinnecock representation. She currently spends her time between Brooklyn and Southampton.

“Shinnecock Voices” is a monthly column in which citizens of the Shinnecock Nation share stories and opinions, discuss the projects and campaigns they’re working on, and allows readers an inside view into their incredible community.